In his book, now nearly 30 years old, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, the philosopher Daniel Dennett (who died last April) claimed that evolution by natural selection deserves the prize for “the single best idea anyone has ever had.” It’s a formidable declaration, but I’ve never heard a worthy counter-claim.

Just to remind anyone who might be a tad rusty on their high school biology classes, what we’re talking about here — evolution — is the result of random genetic mutations in the process of passing the genome (the genetic information carried in the egg or sperm) from one generation to the next. Some small fraction of these mutations are beneficial in that the members of a species that possess them are better adapted to the environment in which they’re born than their sibs. This gives them the edge in terms of survival and — more importantly — reproduction, over those that didn’t get that mutation. So a useful mutation gets passed along.

We humans, together with earthworms and E.coli and redwoods and fungi — all living creatures — came from the same grand (times a billion or so) parent. Every member of every species (two million classified ones, plus uncountable others) alive today is the end point of an unbroken chain of successful ancestors going back nearly four billion years, where “success” means they reproduced. These bodies of ours? We’re just the vehicles that genes employ in their quest for immortality.

For me, what makes this spectacular process so hard to appreciate are the change-points. At what point did my great (x 100 million) grandmother, who looked like an early fish, turn into an amphibian; thence into a shrew-like mammal; and when did that creature morph into an ape; which then, at some point, evolved into someone like Lucy (3 million-year-old Australopithecus); who became — at what point? — human. Someone who, suitably attired, would look like any one of us strolling down Second Street on a Sunday morning.

Trick questions. There were no “points.” Pick, at random, any member of this long, unbroken chain of creatures. Now check out their parents and their immediate offspring. Notice something? They all look about the same. Evolution is gradual, meaning it’s imperceptible from one generation to the next. (A possible exception: Diligent observers of birds on the Galapagos Islands believe they have actually seen evolution in action as a result of rapid changes in their environment.)

The evolutionist Richard Dawkins has a thought experiment on these lines, outlined in his recent book The Magic of Reality (written “for young people” — my kind of book!). He asks me, the reader, to imagine a photograph of one of my parents, say my mother. On that photo, I place a photo of my mother’s mother. On top of that, a photo of her mother…and on and on, a mountain of photos, each photo sitting between a mother and a daughter. All the way back to nearly 400 million years ago. (Allowing an average of four years between generations, that’s 100 million photos, a pile as high as three Mount Everest’s stacked on top of one another.) The last photo in your series is, as I said, a fish, given the name Tiktaalik.

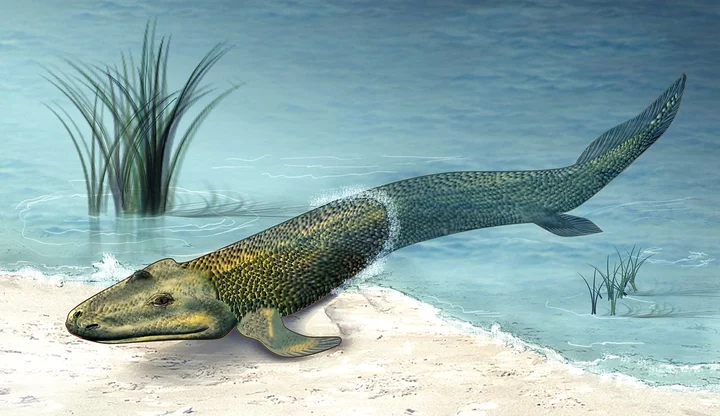

Tiktaalik roseae, a “missing link” fossil between sarcopterygians (bony fish with lobed paired fins) and tetrapods. Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation. Public domain.

That’s my, and your, long ago ancestor, from about 375 million years ago. Tiktaalik was a fish which, over time, evolved wrists and ankles enabling it to use its fins as feet, crawling up from the water to dry land. Tiktaalik (or its close cousin) is the ancestor, not just of humans, but of all non-fish vertebrates.

But — this is the take-home message — there never was a point at which you could say, this generation is fish and this next generation, amphibian: the changes from one generation to the next were too subtle. Similarly, from ape to human, an ape never gave birth to a human. It was all very (very!) gradual. But that’s all it took, thanks to the magic of evolution.

Millions of tiny changes over aeons of time gets you from Tiktaalik to you and me.

CLICK TO MANAGE