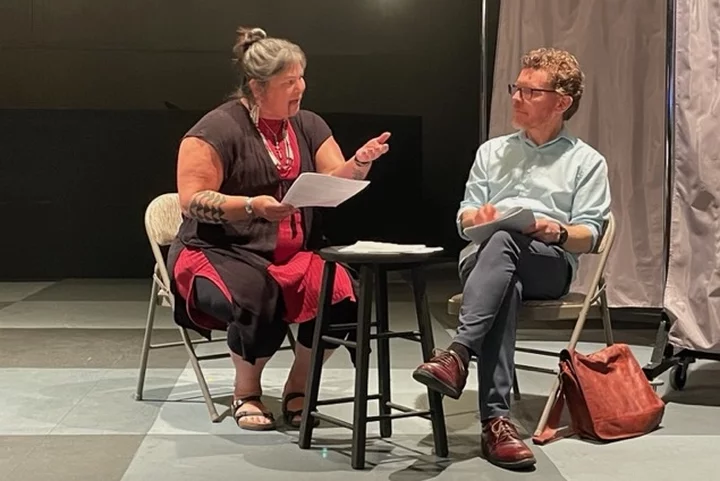

Maggie Peters and Solomon Everta act out a scene during a rehearsal for “Wusatoumuduk: We Make It Burn.” Photo: Michelle Hernandez

###

Local Indigenous leaders hope to reignite the conversation around traditional cultural fire practices in an upcoming multimedia stage play, “Wusatoumuduk: We Make It Burn,” set to premiere at the North Coast Repertory Theater (NCRT) this weekend.

The production, which will be partially depicted in Soulatluk, the language spoken by the Wiyot people, delves into the cultural and ecological importance of traditional fire management practices. The story follows the journey of a young Wiyot woman grappling with her identity as she learns about fire ecology in college and how modern practices conflict with traditional tribal land management techniques.

“She’s learning what it means to be Wiyot and what it means to take part in traditional practices, including cultural fire,” Michelle Hernandez, co-artistic director of “Wusatoumuduk,” told the Outpost in a recent phone interview. “It’s taken modern science a while to get on board [with the practice] but we’ve been talking about how important it is for ages. … I’m an artist, not a scientist, and this is my way of bringing this conversation to a wider audience.”

Native communities have used small, intentional burns as a form of land management for thousands of years. The practice was essentially eradicated with European colonization and the forced relocation and genocide of native people who had historically maintained the landscape. In 1850, the California legislature passed the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, which outlawed intentional burning in the newly formed state. Decades later, the U.S. Forest Service implemented its “10 a.m. policy,” which decreed that all fires must be extinguished by 10 o’clock the morning after their initial report to eliminate fire from the landscape.

The last century of restrictive fire suppression practices has resulted in increased fuel loads (dried grasses, trees, dead leaves, etc.) across the landscape that allow fires to burn longer, hotter and faster, making them more difficult to manage.

For decades, tribes across Northern California have advocated for “good fire” to be reintroduced to the landscape. Various state and federal agencies have implemented prescribed burning practices to remove excess vegetation, but some tribal leaders want to see a more intentional approach to land stewardship.

“The Wiyot people – and many, many other Indigenous peoples across the country – have used cultural fire to help us survive,” Wiyot Tribal Councilmember Marnie Atkins, one of the lead writers for “Wusatoumuduk,” told the Outpost. “Not only did we use fire to manage the landscape [and] keep our communities as fire resistant as possible, but we also used fire to care for the land. Some plants thrive after a fire, not the huge, devastating fires we see now, but the pointed burning of specific plants. We have a reciprocal relationship with the land – we ensure the plants and animals are healthy and well, and they keep us healthy and well.”

Atkins hopes the play will diminish some of the anxiety surrounding cultural burning practices. “I think there is still apprehension among people who think this is something new,” she said. “It’s not new, but I do still hear the apprehension and concern. Understanding the generational, observational knowledge of a landscape and plants and what they need is important – that’s where [tribal communities] come in. We’ve engaged with these spaces for time immemorial.”

Atkins has been looking for a way to bring the subject of cultural fire to a wider audience, either through an educational or artistic medium. Two or three years ago, she struck up a conversation with Calder Johnson, NCRT’s managing artistic director, and asked him if he could help her turn the idea into a stage production.

“In my mind, the place to start was through education and what better way to educate than with art,” Atkins said. “I had been mentioning wanting to do this project for a bit and, one day, Calder happened to be at a meeting where I was talking about this idea. Being as awesome as Calder is, he said that if NCRT could ever be a partner or support this work, or even if I needed help writing a grant, I should reach out.”

“I was more than happy to help Marnie make this idea happen,” Johnson told the Outpost. “Marnie is an incredible person and the whole concept was very inspiring to me. … This is a massive crisis that we have on our hands, and it’s good to see that more entities like CalFire and other state agencies incorporating native knowledge into an effective response, but it still needs to move faster.”

Atkins and Johnson applied for a few grants and secured funding from the California Arts Council, the Upstate Creative Corps and the National Endowment for the Arts.

A few other people eventually joined the project, including artistic directors Michelle Hernandez and Zuzka Sabata, who worked together on the Bartow Project, as well as community contributors, Maggie Peters, Kate Droz and Solomon Everta.

Lynnika Butler, the Wiyot Tribe’s linguist, has also worked closely with the writing team to translate various words and phrases in the play into Soulatluk.

“I’m thrilled that we have the opportunity to reintroduce Wiyot phrases and language to the public sphere,” Atkins said. “[The Wiyot Tribe] has been working on language revitalization for a very long time. Some people have said it is a ‘dead language’, but a language isn’t dead if you have speakers and the ability to learn your language – and we have all of that. … [Soulatluk] isn’t dead, it’s just sleeping.”

The play will also incorporate shadow puppetry developed by James Hildebrandt and performed by Jay Gehr, as well as animations developed by Chantal Jung.

“The animations will be incorporated into the play,” Hernandez explained. “There is a lot of storytelling in this play – all traditional Wiyot stories – and when that happens, we will play an animation of the story as the characters are telling them. The shadow puppets are another aspect of that. It’s like the story is coming to life.”

Shadow puppet slugs, or “Joumashk” in Slouatluk, by James Hildebrandt. Photo: Zuzka Sabbata

The cast of “Wusatoumuduk,” from left to right: K’nek’nek Lowry, Maggie Peters, Deja McCovey Coleman and Solomon Everta. Photo: Michelle Hernandez

The production team will host a free stage reading of “Wusatoumuduk” on Saturday and Sunday, a sort of first draft of the play. Attendees are encouraged to provide feedback in a community “talkback” session after the play.

The writers will incorporate that feedback into a future rendition of the production, which, Atkins hopes, will begin to take form in the coming months. But first, they need to secure additional grant funding. Her ultimate goal is for the play to serve as a foundation of sorts for similar projects on cultural fire.

“Maybe this play will make its way throughout the state or beyond,” Atkins said. “If it resonates with other native communities, maybe they will want to produce this play in their community and add in changes that address their local concerns or put it in their language. We see this as a foundation to build upon. … Maybe we can make a difference.”

There will be two separate stage readings of “Wusatoumuduk: We Make It Burn” on Saturday, June 15 at 7 p.m. and Sunday, June 16 at 2 p.m. More information can be found in the flier below.

###

CLICK TO MANAGE