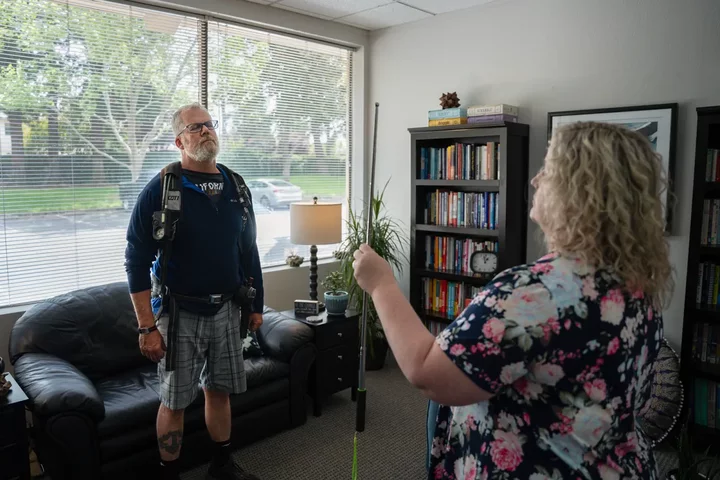

El Capitán retirado de Cal Fire, Todd Nelson, y su terapeuta, Jennifer Alexander, realizan un ejercicio de “brainspotting” como parte de su tratamiento que implica que Nelson use equipo de lucha contra incendios. Foto de Cristian González para CalMatters

Con un diagnóstico de trastorno de estrés postraumático complejo y afectado por frecuentes convulsiones inducidas por la ansiedad, el Capitán de Cal Fire Todd Nelson pasa la mayor parte de sus días en agudo malestar mental. Su terapeuta, Jennifer Alexander, dijo “nueve de cada diez terapeutas no tocarían a Todd ni con un palo de diez pies”.

¿Por qué? ¿Debido al desafío de tratar a un bombero con una condición de salud mental tan grave, incluidos múltiples intentos de suicidio y hospitalizaciones?

No. Porque los terapeutas de California saben que aceptar un paciente en el sistema de seguro de compensación para trabajadores del estado significa que podrían pasar años antes de que les paguen. Además, es probable que las aseguradoras desafíen sus decisiones de tratamiento e incluso citen sus registros.

“Si aceptas un caso de compensación laboral, entiendes conscientemente que no vas a recibir pago durante algún tiempo”, dijo Alexander, una terapeuta de matrimonio y familia con licencia que se especializa en tratar el TEPT y el trauma. Nelson le concedió permiso para hablar sobre su caso. “Tengo varios casos en los que no he sido pagada durante tres años. Tienes que tener pasión para trabajar con esta población”, dijo.

La intransigencia del sistema pone a los médicos en una posición difícil — negar a los pacientes la atención que necesitan o renunciar a su propio pago. Como muchos terapeutas que temen los impactos de interrumpir el tratamiento a bomberos gravemente enfermos, Alexander los trata de todos modos. Luego averigua cómo ser reembolsada más tarde.

“Tienes que tomar una decisión moral-ética — hacer un compromiso con un cliente o un compromiso para ser pagada”, dijo. “El seguro te da un puñado de sesiones, pero con muchos pacientes”, como Nelson, “el trauma no se resolverá en diez a doce sesiones”.

La terapeuta Jennifer Alexander y su paciente, el ex Capitán de Cal Fire, Todd Nelson, en una sesión de terapia. Alexander dice que la burocracia del seguro de compensación para trabajadores disuade a muchos terapeutas de tratar a los socorristas con TEPT. Fotos de Cristian González para CalMatters

Algunos médicos simplemente se niegan a aceptar casos de compensación laboral, dejando menos opciones para los bomberos y otros pacientes con TEPT y otras dolencias graves. Y una carga potencialmente abrumadora para los terapeutas.

El sistema de compensación para trabajadores del estado, administrado por el Departamento de Relaciones Industriales de California, ofrece beneficios para trabajadores privados y gubernamentales cuyas condiciones médicas están relacionadas con el trabajo. Más de 16 millones de californianos están cubiertos.

Los funcionarios del departamento de relaciones industriales se negaron a responder a las preguntas de CalMatters o proporcionar una entrevista sobre cuestiones relacionadas con reclamos de salud mental de socorristas.

La compensación para trabajadores de California es atípica, y no de la mejor manera.

“California continues to experience longer average claim duration compared to other states, driven by slower claim reporting, lower settlement rates and higher frictional costs,” says a 2023 report by the Workers’ Compensation Insurance Rating Bureau, an association of companies licensed to handle workers’ comp insurance in the state.

Only a third of medical losses in California are paid by workers’ comp within two years of an injury, while it’s two-thirds in other states. And about 36% take five years or longer in California, about twice the median in other states, according to the report.

California’s sheer size slows the rate of case closure and reimbursement, said Sean Cooper, executive vice president and chief actuary for the Workers’ Compensation Insurance Rating Bureau. The torrent of claims, the number of attorneys in the system and the complexity of trauma cases bog down an already ponderous bureaucracy.

Because of their cumulative trauma that can stem from an entire career, they often need years of therapy.

Some therapists no longer accept workers’ comp or even private insurance, leaving a patient paying fully out of pocket for mental health care, said D. Imelda Padilla-Frausto, a research scientist at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

“Clinicians often go into private practice because they don’t want to deal with even health insurance. It’s all out of pocket. Then you add workers’ comp on to that, and it’s ‘oh, no’,” she said. “Our health system is administration-heavy.”

Nelson ran smack into that bureaucratic wall. He said he contacted therapists who refused to take insurance or were intimidated by the severity of his diagnosis. “They were being polite, telling me they weren’t taking new patients,” he said.

Nelson, who lives in Nevada City, searched for years for a therapist that would take his case. Experts says there aren’t enough therapists in many rural regions. Photo by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

RAND researchers noted many of these shortcomings in California’s workers’ comp system in a 2021 report.

“The workers’ comp system is excruciatingly slow, doctors are annoyed, not getting paid for extra reports and patients are not getting care,” said Denise D. Quigley, senior policy researcher at RAND and one of the report’s project leaders.

Previous research had identified problems with California’s workers’ comp system, including a heavy burden of administrative costs borne by providers, who also complained about inadequate compensation.

“It’s hard to find providers willing to take on the struggle for workers’ comp. There are some that will just take patients outright, but a majority can’t,” Quigley said. “They recognize that if they take them on there will be self-pay, it’s months to get paid, and unless they are part of a really large organization, they can’t cover that cost.”

Nelson recalls traumatic memories of his time as a firefighter during a treatment session. Photo by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

Frustration is winnowing the ranks of providers qualified to treat PTSD and related issues, according to Joy Alafia, executive director of the professional group California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists.

“We have a shortage of mental health professionals overall in California, and with the added paperwork and denials…you can understand why there is a natural inclination to choose a different path. The administrative burden is so great, you need assistance and technology to help overcome the barrier,” Alafia said.

In four years, the demand for mental health care in California will exceed the workforce capacity, according to a UC San Francisco analysis.

Alafia said the administrative burden from workers’ comp sometimes forces therapists to bring on more staff to “wrestle with companies” that reject what doctors view as a sufficient number of patient visits.

Eso puede dejar a los pacientes vulnerables, dijo Alafia, lo cual es un resultado final inaceptable.

“Tenemos preocupaciones sobre la continuidad de la atención”, dijo ella. “Cuanto más tiempo pasan los terapeutas matrimoniales y familiares haciendo papeleo, menos tiempo con el cliente. Y eso es por lo que las personas entran en esta profesión en primer lugar.”

Esta historia fue posible en parte gracias a una subvención de la Fundación A-Mark.

CalMatters.org es un proyecto de medios sin fines de lucro y no partidista que explica las políticas y la política de California.

CLICK TO MANAGE