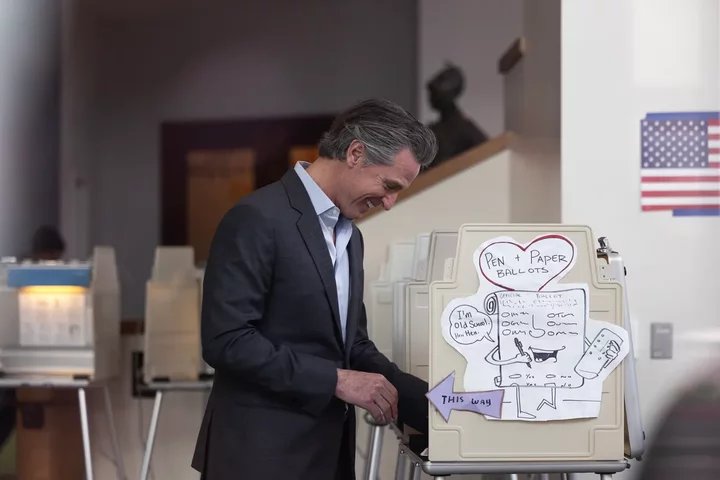

California voters in the March 2024 election narrowly passed Proposition 1, a proposal to fund new construction of housing and treatment facilities for people with serious mental health illnesses. Gov. Gavin Newsom championed the measure and called it critical in addressing the state’s homelessness crisis. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters Credit: Miguel Gutierrez Jr.

After days of uncertainty, the results are finally in: Californians, by a slim majority, have voted to throw their support behind Gov. Gavin Newsom’s latest effort to overhaul how the state cares for people with serious mental illness.

The Associated Press on Wednesday declared that Proposition 1 passed by the narrowest of margins, 50.2% to 49.8%.

The passage of the two-pronged ballot measure will give Newsom funds to fulfill promises he has made while rolling out a series of other mental health policies in recent years – more housing, more treatment beds and a concerted focus on unhoused people with serious mental illnesses.

But it leaves the governor’s critics — including disability rights advocates and individuals living with mental illness — worried about cuts to other mental health programs and fearful it will result in the state placing more people in involuntary treatment.

The governor championed Prop. 1, which he has said “will help California make good on promises made decades ago.”

The initiative includes a $6.4 billion bond to pay for treatment beds and permanent supportive housing. It also requires that counties spend more of the mental health funds they receive from a special tax on income over $1 million on services for people who are chronically homeless.

While the ballot measure initially seemed a shoo-in, public support wavered in recent months. In part, that’s because the state’s ballooning deficit came into stark focus — with the Legislative Analyst’s Office projecting last month that it might be as big as $73 billion. Opponents of the ballot measure had also raised concerns that it could siphon money from community mental health organizations, possibly causing some to close.

Public concern about homelessness and a multi-million dollar advertising campaign eventually carried the measure to victory — but just barely.

“It’s still not a huge vote of confidence,” said Thad Kousser, a UC San Diego professor of political science. He says Newsom failed to convince voters of just how effective other billion-dollar investments in helping unhoused people have been.

“To me, given the strong message, the money behind the message, the lack of organized opposition, I would have guessed at the beginning of this campaign it was headed for a 60-40 win,” Kousser said.

Kimberlee Booth, center, of San Luis Obispo marches with other supporters following speeches at a rally in support of Prop. 1 at the state Capitol on Jan. 31, 2024. The proposition aims to reform mental healthcare in the state. Photo by José Luis Villegas for CalMatters

Nevertheless, it did squeak by. And under the just-approved ballot measure, counties are now required to invest 30% of the money they receive from the state’s “millionaire’s tax” into housing programs, including rental subsidies and navigation services. Half of that will be used to target individuals who are chronically unhoused or living in encampments. Up to a quarter of the money could be used to build or purchase housing units.

The second part of the measure, the bond, is divided into two parts. About $4.4 billion will go toward inpatient and residential treatment beds. The rest is earmarked for permanent supportive housing, half of which would be set aside for veterans.

Darrell Steinberg, the mayor of Sacramento who co-authored the 2004 law that created the millionaire’s tax, said that, back then, he could “only dream that there would someday be a governor that would make mental illness and fixing the broken system a cornerstone of his governorship.”

“Gavin Newsom has done that,” he said.

Gavin Newsom’s mental health plans

Mental health has been one of Newsom’s priorities since before he took office. He campaigned for the governorship with big ideas about how California’s mental health system might be fixed and, specifically, about how funds from the “millionaire’s tax” for mental health could be better used.

In a 2018 post on Medium months before he was elected, Newsom decried the state’s lack of commitment to improving mental health care.

“We fall short because we lack the bold leadership and strategic vision necessary to bring the most advanced forms of care to scale across the state,” he wrote. “We lack the political will necessary to elevate brain illness as a top-tier priority. We lack the unity and fervor needed to rally the medical and research communities around an unyielding search for ever-better diagnosis and treatment. We’re all living with the fallout.”

Supporters of Prop. 1 march at the state Capitol in Sacramento on Jan. 31, 2024. Photo by José Luis Villegas for CalMatters

The need for mental health treatment continued to skyrocket since he took office. The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically worsened the problem. The public experienced escalating trauma and anxiety, while mental health providers became increasingly burnt out.

Meanwhile, the number of unhoused people in the state continued to explode– growing 40% since 2018, the year Newsom was elected, to a current estimate of 181,000.

In response, Newsom has championed a stream of major mental health initiatives. These include:

- A $4.7 billion package of programs for children and youth mental health.

- The creation of new court systems to address the needs of people with serious mental illness. They’re called Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Courts.

- A new law that makes it easier to force certain people with serious mental illnesses into involuntary treatment. It amended the definition of “grave disability” originally laid out in the landmark 1967 Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, which limited involuntary confinement in the interest of protecting the civil rights of people with mental illnesses.

- In addition, his administration is also overseeing the implementation of a statewide effort that promises to expand and streamline access to mental health care for people insured by Medi-Cal, the public insurance program for low-income Californians. It’s called California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM).

Expecting better outcomes

Sen. Susan Talamantes Eggman, a Stockton Democrat who has carried legislation to enact Newsom’s mental health programs, said the stream of recent policy changes will eventually lead to changing outcomes – but not yet.

“Policywise, the landscape is shifting dramatically,” she said. “It will take a few years for practice to catch up.”

She emphasizes that Prop. 1 has a lot of transparency and accountability measures attached, to ensure that the measure leads to concrete change.

But Newsom’s critics worry that many of his big initiatives – including Prop. 1, CARE Court and the broadened definition of grave disability – reflect an effort to move the state toward more forced treatment.

“It’s all in preparation of hiding the homeless instead of helping them,” said Paul Simmons, executive director of Californians Against Prop. 1. “It will still be a bridge to nowhere, pushing people into a system that can’t even handle what we have now.”

Questions about Prop. 1

Alex Barnard, a New York University professor who has written extensively about California’s mental health system, called fears of returning to mass reinstitutionalization “a little bit overstated.” But, he said the state is indeed moving toward a more paternalistic and institutional approach toward treating the most seriously mentally ill.

The passage of Prop. 1 will help the administration to fully implement both CARE Court and the recent law expanding the definition of grave disability. But it also raises some thorny issues, he said.

One of these: What type of treatment beds will the state purchase with the bond money and where?

Another: How will county systems deal with the money they stand to lose for mental health services?

A state facing a massive deficit is not coming to the rescue, he said.

And then, there’s the question of just how transformative this latest influx of money will prove to be for actual Californians.

“The status quo has been remarkably enduring even in the face of a lot of attempts at reform,” he said. “The system has had an incredible amount of inertia.”

###

CalMatters reporter Jeanne Kuang contributed to this story. CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE