A rite of passage for outdoor folk living in our glorious neck of the woods is to hike the Lost Coast Trail, the 25-mile path from the mouth of the Mattole to Black Sands Beach in Shelter Cove. A glance at a road map of California gives a feeling for the topography, with highways hugging virtually the entire length of the state, except for the stretch where Highway 1 turns inland north of Fort Bragg a mile north of Westport-Union Landing State Beach (and great campsites). The road doesn’t return to the sea for another 80 miles, west of Petrolia. That un-roaded stretch, where the King Range sweeps steeply thousands of feet down to the sea below, is the most rugged coastline in the contiguous U.S. No wonder early road builders gave up on it and built the Highway 101 inland.

The trip takes a leisurely 3-4 days, camping at one of the many inviting streamside gullies en route. Everyone we have seen on the trail is heading south, that is, starting at the Mattole campground, where it’s possible to leave a vehicle for several days. Even if you don’t go the distance, the day hike to the Punta Gorda light, a seven-mile round trip, gives a worthy taste of the wild coastline avoided by early road-builders. Don’t go without (1) checking tides, three stretches of the trail are impassable at medium to high tide, including between Mattole and Punta Gorda; and obtain backpacking and fire permits from the BLM if you’re camping.

Photos: Barry Evans.

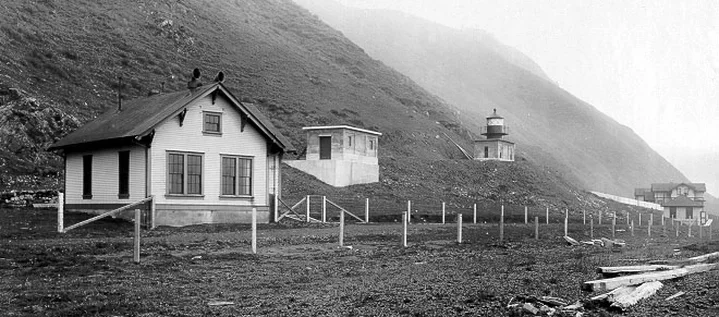

Not much is left of the Punta Gorda lighthouse settlement now. Originally, in addition to the light itself, it comprised three houses, several storage sheds and a workshop. Supplies were brought in on horseback from Petrolia, 11 miles away. In winter, washed out roads and high winds cut the outpost off for weeks at a time. A diesel generator supplied power for the light.

Punta Gorda Light settlement in its heyday. Photo: US Coastguard

Besides the shell of the lighthouse, all that remains today is the oil storage building on the right. (Barry Evans)

The light was originally requested by the Lighthouse Board in 1888 following a series of wrecks, and between then and first light in 1912, nine more ships were lost. One of these, the schooner Columbia, was wrecked in 1907 with the loss of 87 lives, giving impetus to funding construction of the light. Up to 30 Spanish galleons may have foundered on the rocky shore south of Cape Mendocino, the lost ships out of hundreds that made the four-to-six month voyage from the Philippines to New Spain (now Mexico) between 1565 and 1815. Every year, over a 250-year period, between two and four huge “Manila galleons” built of Philippine hardwood made four-to-six-month eastbound voyage from Manila to Acapulco, bringing cargoes of porcelain, ivory, silks, wax, chinaware and spices. The voyages only ceased when the Mexican war of Independence put a stop to the trade in 1815, six years before Mexico finally seceded from Spain after a long struggle.

Model of a “Manila galleon” in Acapulco museum. Photo: Barry Evans.

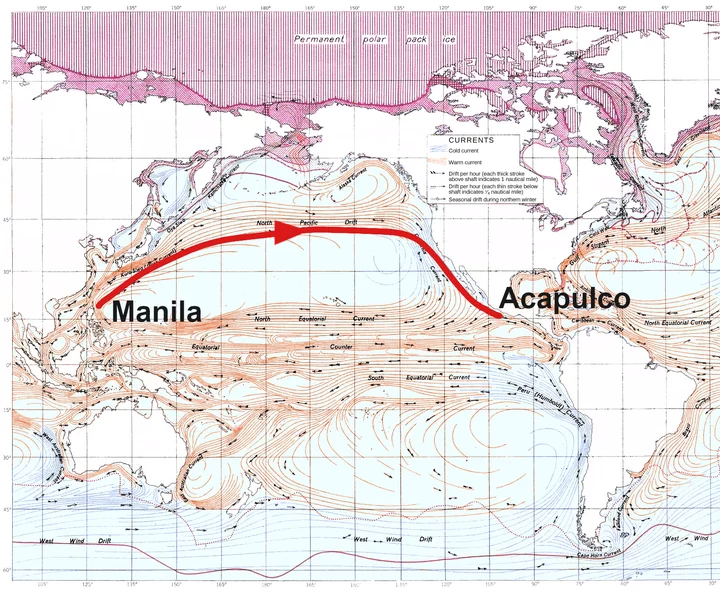

The route, which took advantage of easterly winds and the North Pacific Drift Current at around 45 degrees north latitude, had been pioneered by the near-mythical Basque seafaring monk, Andrés de Urdaneta (1508-1568), and used Cape Mendocino (California’s westernmost point) as a navigation point. From there, the galleons followed the coastline down to Acapulco.

Urdaneta’s route from Manila to Acapulco, via Cape Mendocino. 1943 US Army chart.

Which brings us to the Legend of King Peak. In the July 1963 issue of Western Folklore magazine, Humboldt county author Lynwood Carranco retold a story he’d heard from legendary Humboldt Times columnist Andrew Genzoli. Genzoli claimed to have heard the following when he was a youngster from Johnny Jack, a Mattole and Wiyot tribal member who lived at the mouth of the Mattole: A Spanish ship carrying a rich cargo of gold, gems and silk was wrecked on the Lost Coast south of the Mattole. The crew either drowned or were killed by local Native Americans, who recovered the cargo and stashed it in a cave below King Peak, tallest mountain on the Lost Coast. An earthquake subsequently sealed up the opening of the cave, and (you have to take my word on this) the loot is there to this day.

Does this tale, passed down through the years by Mattole tribal members, explain the disappearance of one of the 30 missing Manila-Acapulco galleons? Get out there, locate the cave, and we’ll find the truth!

CLICK TO MANAGE