Alders and willows crowd along the edges of Redwood Creek. | Photo: Andrew Goff

###

Standing at a property high above Redwood Creek, overlooking the lush green valley surrounding the small, unincorporated community of Orick, Ron Barlow points to a farmhouse on the south side of town that’s been in his family for generations.

“I grew up on that ranch,” he says. “I’m third generation, and now with my grandkids, we’ve had five generations of people on this farm. That’s generations of people working this land and making sure these fields and the cattle are taken care of. And if the creek overtops the levee, it’s not just a few people that will be affected. This is my home, and the herd of sheep out there and the cows having their babies, this is their home, too.”

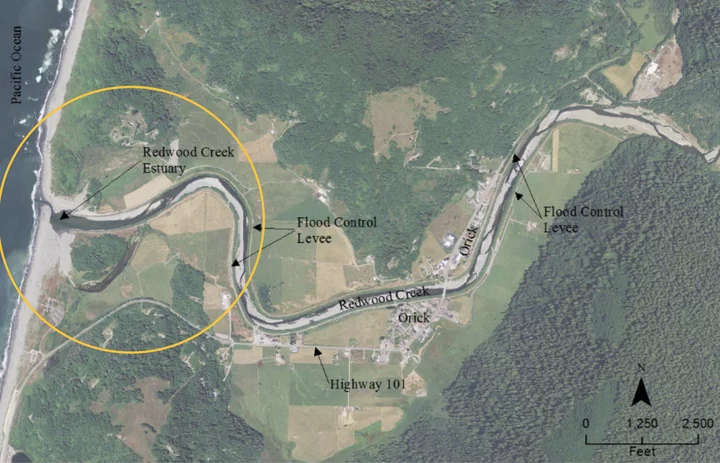

The levee system that runs through the heart of Orick consists of two earthen levees that flank each side of Redwood Creek. Over the years, the main channel has become impaired by vegetation and sediment deposits that restrict the channel’s capacity and increase local flood risk.

Over the last three decades, Barlow has written countless letters and convened dozens of meetings with county, state and federal officials on behalf of the Orick Community Services District (CSD) Board of Directors, which he chairs, to sound the alarm over ongoing maintenance issues with the Redwood Creek levee system. If the levee isn’t repaired – and soon – Barlow fears the creek will breach the levees and decimate the struggling community.

At the beginning of this year, during one of the worst storms of the season, Barlow and a few others walked along a section of the levee behind the Shoreline Market to look for any “bad spots” that could cause the levee to fail. “Redwood Creek came within about four feet of overtopping [the levee],” he said. “I’m going to tell you, if there had been snow in the mountains, Orick would not be here today. Or one-half of it, at least.”

As the agency responsible for levee maintenance, the County of Humboldt periodically removes sediment and vegetation from Redwood Creek to increase the channel’s capacity. However, it’s been about 10 years since any substantial maintenance occurred.

“It’s incredibly frustrating,” Barlow said. “People tell me that I’m way too passionate about these levees, but that’s what keeps our little community here. Highway 101 running through town and those levees – that’s why Orick is still here.”

At the Orick Community Hall a few hours earlier, we stood around a table neatly lined with manila folders full of old newspaper clippings, Xeroxed letters to elected officials, county staff reports, signed petitions and federal documents dating back to the late 1960s.

“The condition of the Redwood Creek channel has become a big concern to those of us living in the Redwood Creek Valley,” reads a Sept. 15, 1997 letter to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the agency that constructed the levee system in the mid-1960s. “We feel our homes and ranches could be in jeopardy.”

Another letter, from Oct. 5, 2004, asked for Congressman Mike Thompson’s help in addressing “a most serious situation” in Orick. “At this time, we have gained nothing in the efforts to protect our families, farms and businesses from flooding,” the letter says. “The capacity of the levee has dropped from the original 250-year flood down to a mere 50-year flood. There is a lot at stake here in Orick. Many of us have witnessed the floods prior to the levee being built to protect us, and remember the heartbreak and devastation.”

A petition attached to the letter (signed by about two dozen Orick residents) urges the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors to uphold the county’s duty to maintain the levee, as stipulated in the operation and maintenance manual for the Redwood Creek Local Flood Protection Project. “The county supervisors need to recognize this situation is very serious, and immediate attention is essential before another winter season is upon us,” the 20-year-old petition states.

Each letter depicts an increasingly desperate situation in Orick, one that persists today.

“The levees are the main thing,” Barlow explained, “but there’s a lot of other stuff, too. Our volunteer fire department is struggling. We work hard to secure funding but it’s difficult to keep it all going. We’re patting people on the back, saying come on, come on, we’ve got to do this, but I sometimes wonder, when do I bail off this boat?”

Orick’s heyday has long since passed, but Barlow is a firm believer that a little investment could go a long way for the economically depressed community and its 300-odd residents. The interest is there, but it’s slow going.

Last year, the Yurok Tribe received a $6 million grant to build a “state-of-the-art” fuel mart, laundromat and tribal office on the footprint of the aging Shoreline Market. The Orick CSD was recently awarded $900,000 in federal grant funds to build a solar-powered microgrid to provide reliable power for critical infrastructure for the volunteer fire department, the community hall, the water pumping station and the grocery store. The county is also working with the Orick CSD to improve its water and wastewater infrastructure.

“It’s slowly coming along, but we have a lot going on in this small community,” Barlow said, readily adding that the Roosevelt Base Camp hotel was recently renovated and a new food truck is selling wood-fired pizza. “That said, our main asset is the levee system. And without that, there’s no need for us to even be here.”

However, the core of this complex issue isn’t maintaining the levee system. It’s the fact that the levees were built at all.

The Shoreline Market at the southern end of Orick. | Photo: Andrew Goff

A History of Floods

Humboldt County is no stranger to torrential rain and inundated rivers, but after the unprecedented floods of 1955 and 1964 – both declared 1,000-year flood events, meaning there is a 1 in 1,000 chance of a similar flood occurring in any given year – devastated the region, local and federal officials agreed that it was time to intervene.

“At that time, Orick had a lot of dairies and a booming timber industry, so the Army Corps of Engineers came to the conclusion that it was in the federal government’s interest to build a levee at Redwood Creek,” Hank Seemann, the county’s deputy director of environmental services, told the Outpost during a phone interview. “As you can imagine, the Board of Supervisors was probably very willing to make that deal because of the loss that everyone had experienced during the 1964 flood. So the county agreed to operate and maintain the levee after it was constructed.”

In 1966, the Army Corps of Engineers broke ground on the Redwood Creek Flood Control Project, a system of two earthen levees that run along the lower 3.4 miles of Redwood Creek, all the way out to the estuary. The levee was certified by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to provide 250 years of flood protection withstand a 250-year flood event along Redwood Creek. When construction wrapped up in 1968, the Army Corps turned over maintenance responsibilities, including “periodic” sediment and vegetation removal, to the Humboldt County Department of Public Works.

But just a few years after the levee system was constructed, Redwood Creek became impaired by large sediment deposits, dramatically reducing flood capacity. Eventually, the channel became overrun with vegetation.

The county went in and cleared the channel of sediment and vegetation in the late 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, though it’s not clear how much material was removed at that time.

“In 1987 and 1988, over 200,000 cubic yards of sediment were removed to provide construction material for a major state highway project,” according to a 2019 letter to the Army Corps of Engineers signed by Seemann. “Humboldt County initiated a program of nearly annual treatments in the mid-1990s. Sediment was removed between 1996 and 2000 and between 2004 and 2010, in volumes ranging from approximately 2,700 cubic yards to 41,000 cubic yards per year.”

When the flood control project was constructed in the 1960s, the county didn’t know the channel and the estuary would fill up with sediment so quickly. The project’s design is a big part of the problem.

“Literally, the first winter after it was constructed, there were observations of gravel deposits within the levee embankments,” Seemann said. “What that tells us is that the original geometry with having a lowered and flat channel bottom is just not sustainable, and it’s not consistent with a watershed that generates and conveys sediment. … It wasn’t that the design was inherently unstable, but it didn’t achieve the equilibrium that they envisioned, which reduced the capacity of the levee system.”

The levee was built to withstand floodwaters up to 77,000 cubic feet per second (CFS), which is about 40 percent more than the 1964 flood, according to the project manual. A hydraulic analysis from 2014 – the most recent analysis on file – determined that accumulated sediment had diminished the channel’s capacity by as much as 25,000 CFS, reducing flood protections for Orick residents and critical habitat for threatened salmonids.

A study from the Army Corps of Engineers estimated that 430,000 cubic yards of sediment – 93 percent of the “original excavation volume” – would need to be removed from the channel to restore 250-year flood protection. Doing so would cost the county over $4 million, Seemann said, and it’s difficult to justify a project of that scale when it just doesn’t last.

“A massive amount of sediment was removed from the channel in the 1980s to help build the bypass road for Redwood National Park … but the area they excavated filled in over the next several years,” he said. “So, what that tells us is you can do some sediment removal, but it won’t last long.”

Another option: The Army Corps of Engineers could come in and raise the levee to increase capacity in the channel. However, that option would be even more expensive – somewhere in the ballpark of $20 million.

“We have to work within a benefit-cost ratio – the benefits need to outweigh the cost,” Seemann continued. “The concept of a major levee improvement project, it’s just, it’s hard to see how that could pencil out. … It’s not an urgent situation. There isn’t an imminent risk, so it makes it even more difficult to justify. … If there was a 50 percent chance that the levees would be overtopped or compromised, that would justify urgent action to either repair the levees or work on trying to relocate the town. However, we’re not at that point.”

Well, what about vegetation removal?

Over the years, Redwood Creek has become overgrown with vegetation – mostly fast-growing alder and willow trees – reducing the channel’s ability to move floodwaters. Trees growing in the channel can slow flows and “enhance deposition,” making it easier for sediment to accumulate along the creek bed and tree roots. However, overgrown vegetation is only considered to be a “contributing factor” to the levee’s ongoing issues, Seemann said.

Aerial view looking east.

Aerial view looking west.

“It’s hard to really quantify the effect of vegetation,” he explained. “It adds roughness or friction to the flow … that can encourage more sediment to deposit. … I mean, when Redwood Creek really rips, the vegetation – a lot of those willows and alders – kind of bend down and get ripped away. Not all of them, but that does happen during high flows.”

In those first few decades after the levees were built, county staff and chainsaw-wielding locals would just go in and cut back overgrown trees. Now, that type of work requires a federally-issued permit because Redwood Creek provides critical habitat for several salmonid species, including federally listed coho salmon.

“This is where it gets confusing with the Army Corps of Engineers,” Seemann explained. “They’re still involved with the levees because it’s considered a federal levee system. So they’ll do periodic inspections and … support the county in maintaining the levee, but they also have a regulatory role. If there’s an activity that requires a permit through the Clean Water Act, the Army Corps’ regulatory branch administers those permits. If the Endangered Species Act is involved, they have to refer that permit application to the National Marine Fisheries Service or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, depending on what species are involved.”

When the county applied for a permit in 2000 to remove sediment and vegetation from Redwood Creek, the Army Corps forwarded the application to the National Marine Fisheries Service (aka NOAA Fisheries) for environmental review, which usually takes about 90 days, according to Seemann. The permit wasn’t issued until 2004.

“It took three and a half years to issue the draft biological opinion, which is far beyond the timeframe for these documents,” Seemann said. “With an extension, they can go to 135 days, but they blew through that timeline, too.”

In its biological opinion, NOAA Fisheries “blindsided” the county with a determination that its plans to remove sediment and vegetation from Redwood Creek would jeopardize threatened salmonid species. NOAA Fisheries issued a counter-proposal that asked the county to pursue estuary restoration first.

“So, we had discussions about that over the course of two and a half years, and we concluded that we couldn’t accept their proposal,” Seemann said. “There’s no way we could commit to that because that’s a huge, multi-million-dollar endeavor.”

Map: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Restoring the Redwood Creek Estuary

When the levee system was constructed in the 1960s, the Army Corps of Engineers didn’t evaluate how it would impact the Redwood Creek estuary and its ecosystems, at least not to the degree it would have in 2024.

“Today, I think the Army Corps of Engineers would have a different perspective on levees and their suitability within the floodplain,” Seemann said. “After the 1960s, the Army Corps essentially got out of the levee-building business … because there’s an awareness that levees come with tradeoffs. Whether [levees] are suitable in a floodplain is a bigger question today than it was considered back then.”

The levees were built before the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the nation’s first major environmental law, was enacted in 1970. The landmark legislation, often called the “Magna Carta” of Federal environmental laws, requires federal agencies to consider the environmental impact of their actions. The Clean Water Act (CWA) and the Endangered Species Act (ESA) were signed into law just a few years later.

Leslie Wolff, a local hydrologist with NOAA Fisheries, told the Outpost that the levee design “would have never made it through those environmental laws.” Moreover, Wolff said the Army Corps of Engineers no longer designs levees to meet a 250-year flood event, making it less likely that the levee system would ever be fully restored.

“I want to stress that NOAA Fisheries wants to focus on solutions to these long-standing issues for fish and for communities,” she continued. “We understand issues surrounding public safety, and we would never want to promote anything that does not result in public safety. … With that said, our charge is under the ESA, and we have these fish that are barely hanging on.”

If you look at an aerial view of the Redwood Creek estuary, you can see where the levee system cut off a large meander on the south side of the main channel. Doing so not only reduced the size of the estuary, it also impaired its ecological function.

“[The levees] have destroyed estuary habitat,” Mary Burke, California Trout’s North Coast regional manager, told the Outpost. “[The flood control project] fundamentally disconnected the river from its ability to slow, spread and connect to wetlands and form a lagoon, which was historically there. The levees even cut off a large left meander that used to go around an island. This whole rich dynamic of an estuary, which connects to freshwater coming from the hillslopes, is just cut off because of the levees.”

Burke became familiar with the Redwood Creek watershed when she started working on a project to restore Prairie Creek, a tributary of Redwood Creek located about 3.5 miles upstream from the estuary. The Prairie Creek Restoration Project, which broke ground in 2021, centers around the former site of the Orick Sawmill – ‘O Rew in the Yurok language – a 125-acre property at the gateway of Redwood National and State Parks. The project aims to enhance aquatic habitat and floodplain connectivity in the Prairie Creek watershed.

However, if Redwood Creek’s estuary isn’t restored, the Prairie Creek project and goals for salmonid recovery would be “less successful overall,” according to Leonel Arguello, deputy superintendent for Redwood National and State Parks.

“A restored Redwood Creek estuary can provide anadromous salmonids with optimal habitat for growth and marine acclimation, increase riparian cover, create off-channel habitat, lower water temperatures, and decrease predation,” Arguello told the Outpost. “Fully restored hillslopes upstream of Orick in Redwood National and State Parks and restoration of the Redwood Creek estuary is critical to the overall goal of improving opportunity for salmonid recovery.”

For the last decade, Arguello, Burke and Wolff have been working with the Army Corps of Engineers, the County of Humboldt, the Yurok Tribe and local landowners to form a collaborative focused on restoration efforts and “win-win” solutions for everyone involved, but it hasn’t been easy. Naturally, everyone involved has their own set of priorities.

“You know, you have state lands, you have a federal project, and then you even have a local agency – in this case, Humboldt County – and you have to figure out how to get all alignment across the agencies, as well as landowners and all the various interests,” Burke said, adding that there will always be tensions when it comes to land and water use. “Through intentional and slow relationship building we were able to tease apart what our shared interests are, and we have advanced to this position where we’re ready to go into a feasibility design process.”

While estuary restoration would largely exclude the portion of the levee system that runs through Orick, restoration efforts are still intrinsically tied to the levees and require federal approval.

In this case, the collaborative wants to “modify the levee footprint to help restore the estuary and its function,” Wolff said. One way to do that is to go to Congress. Another way is to file a request through the Army Corps of Engineers’ Continuing Authorities Program (CAP) under Section 1135 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1986.

“[T]he County put in a request for a CAP 1135 federal interest determination, and the Army Corps of Engineers determined it is in the federal interest to move forward with the next step, which is the feasibility study,” Wolff explained. “It’s my understanding that the feasibility study is not only the scientific study that develops different design alternatives for levee configuration that will allow for the restoration of the estuary, but it also would take us through the NEPA process.”

That process will probably take about two and a half years, she said. Once that’s complete, the collaborative will finalize the design selected through the NEPA process and apply for various environmental permits to move forward with estuary restoration.

The restoration project is a huge step toward addressing ecological concerns in Redwood Creek. When it’s all said and done, young salmonids will, once again, have access to critical habitat in the estuary and adjacent wetlands.

However, estuary restoration doesn’t address immediate concerns about the integrity of the levee system.

‘They have to do something’

As the rainy season quickly approaches, Barlow worries that this will be the year the levees fail. Asked to respond to Seemann’s claim that there is no “imminent” flood risk to Orick, Barlow reiterated what happened back in January when Redwood Creek came within just a few feet of overtopping the levee.

“We may have dodged a bullet during the storm this year, but we’re headed for a mess,” Barlow said. “My concern is that the alders are getting so big that they could uproot and tear the rock face loose. That would really create a problem. … They have to do something.”

The storm that happened in January “definitely caught [the county’s] attention,” Seemann said. “One of the things we realized is that we need better coordination in responding to flood events in terms of notifying emergency responders, being prepared to notify the public and activating emergency services.”

The Humboldt County Office of Emergency Services submitted a grant application to the state Department of Water Resources seeking funding to improve flood monitoring along local levees and update the county’s safety plan. Seemann said the county is also working to improve lines of communication with Orick’s community leaders, the volunteer fire department and other responding agencies.

“Unfortunately, there’s just no way for us to eliminate risk behind a levee, but we can try to understand it and then communicate it and manage it to the extent we can,” Seemann added. “What we can do is improve our readiness for flood events, and that’s in the near-term plan.”

That said, Seemann acknowledged the unfortunate situation surrounding Orick and admitted that federal investments are often “stacked” to benefit cities rather than small, rural communities.

“Orick’s safety is critically important,” he said. “Orick deserves protection and investment just like any other community in Humboldt County. … There’s definitely an awareness that they’re an economically disadvantaged community [with] limited resources and capacity. And it is a priority of mine to try to find ways to work with Orick and help them – not just with the levee, but with improving their wastewater infrastructure and trying to help with other things.”

CLICK TO MANAGE