Grant and Dax Williamsons’ Alcohol Abuse II. Photos: Dezmond Remington.

The car is long.

Really long.

The whole thing is a javelin, a narrow wedge that rides on foot-wide tires in the back and skinny little wheels in the front. The driver’s seat is a foxhole. The exposed engine lives as a permanent rear passenger and drinks nothing but grain alcohol.

Its torque? Practically instantaneous. The handling? Not good, but that doesn’t really matter because it only goes straight. But just how fast can the thing go?

It’s slower than a Prius.

Despite its aerodynamic stylings, the so-called Alcohol Abuse II only spits out around five horsepower and tops out at 85 miles an hour. It’s a junior dragster — a baby brother to the fire-eating V-8s that can rip through a quarter mile in less than 10 seconds —but it’s still a nasty little thing that can whip some heads back pretty hard.

Alcohol Abuse II is the shared love between Grant and Dax Williamson, a Eureka-based father and son duo that race junior drag events from the Samoa Drag Strip to Las Vegas. There’s a deep field of junior drag racers in Humboldt, ranging in age from as young as 8 to as old as 17. Races are an eighth of a mile long. The rules are a little complicated — for safety and to prevent winners from only being kids with parents who can afford to dump money into the cars, racers aged 13 and up can’t make the run in under 7.9 seconds under the National Hot Rod Association rules, and younger drivers have to go even slower. Drivers race in head-to-head matchups. False starts (called “red-lighting” in drag racing) are disqualifications. Racers compete for points, and the season runs from April to September.

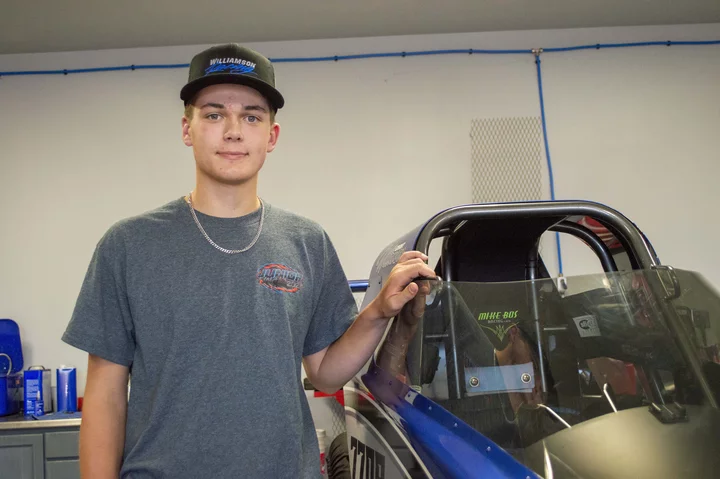

Grant Williamson poses next to the Alcohol Abuse II.

Junior drag isn’t most racers’ first motorsport. Grant Williamson, 15, has been auto racing in some form or another practically since he could walk. He started on go-karts when he was 8. When he was 13, he had an opportunity to sit in a junior drag car at a racing event. He was captivated. Soon after, Grant and Dax drove to Canada and bought their first dragster.

Twelve-year-old Jeremy Johnson’s gateway was through his father Matt, a lifelong auto enthusiast who owns a heavily modified Honda Civic that makes 1,500 horsepower. Jeremy started racing dirt bikes when he was 4, and when he was 8 he tried a junior dragster for the first time.

All three of his younger brothers also race; Jeremy and his 9-year-old brother Logan went head-to-head several times last season. Jeremy won most of the matchups, but Logan snatched victory from his jaws in the final round of a competition once.

“I was very confident,” Logan said. “So I beat Jeremy, and he got really mad.”

Isabel Fuentes-Zittel stands next to her junior dragster. Photos: Dezmond Remington.

For Isabella Fuentes-Zittel, 15, this season’s top overall scorer at the Samoa Drag Strip, the start of her fascination was just as simple — all it took was a rip down the track in a family friend’s junior dragster and she wanted in. But the Fuentes-Zittels are not a racing family, and did not have the $8,000 to spend on a car plus the money for safety gear. Isabella had to raise the money herself, going around Eureka to get sponsorships.

“I had to make this whole list, this pitch of what I was going to say,” Isabella said. “I remember sitting in the living room, having my mom help me write it down, and I’m like ‘I can’t do this, Mom, I can’t do this!’ I was in tears. I would have panic attacks before going into the places, like, ‘Dad, help me, I can’t do this.’ And then I just did it, got it done, got it over with. It was rough, but we got through it…[what made it bearable was] the thought of being able to drive the car. I would just replay the moment of me going doing the track and think, ‘It’s all worth it.’”

Her dad Todd laughed. “She’s addicted and she doesn’t even know it.”

###

Drivers and their parents spend hours tightening bolts, replacing gaskets, changing fluids, swapping engines, installing clutches — the cars are babied, carried hundreds of miles in trailers full of tools and spare parts, before being forced to work harder than any single-cylinder engine should have to. Racers spend hours and hours maintaining the cars, traveling, sharpening their reaction times until the space between the go-light turning green and the accelerator being slammed into the carbon fiber frame measures only two-one hundredths of a second. The time investment adds up. Every parent said their children do well in school and make sure they know it’s their top priority, but for a couple of them the allure of professional drag racing outweighs all else. The Williamsons spent 26 weeks out of the last year on the road traveling.

“This is probably the biggest commitment I have as a 15 year old,” Grant Williamson said. “Even my job — still a big commitment, but this is probably the biggest thing, because this will really lead to my future and possibly a million-dollar paycheck.”

Isabella Fuentes-Zittel is dual-enrolled in community college and her high school and isn’t concerned about what she’ll do when she ages out of junior drag, though she does admit that it can be difficult to find time to do school and compete and maintain the car.

There’s camaraderie in the pits and on the bleachers between parents too, who get time to spend with their kids and chances to watch them win races.

“My car racing has always been a passion for me in my life,” Matt Johnson said. “And I’ve done eight seconds in the quarter mile at 175 miles an hour. It’s super freaking cool. But I’ve never felt as good as I feel when any one of those boys wins a race. And it could be a regular race, nothing special, and it’s still the coolest freaking thing in the world for me. It’s just those proud dad moments, and I get to have them pretty often.”

Many of them are also active participants in the process. Part of the byzantine scoring system is guessing how fast a car will run the race, but many parents assume that responsibility, considering factors like wind speed, air density, humidity, temperature, and any other million factors before “dialing it in.”

All the parents mentioned how grateful they were that so many other parents were so supportive of each other. When a part fails, another is always willing to give it to them, even when their kids are competing against one another.

“They’re all helpful parents out there,” Dax Williamson said. “If they see you need help — and we’ve lent out parts to other kids — then we’re going to race! Let’s have a good time, but let’s also have a good race. Let’s not win because you’re broken.”

Jeremy Johnson shows off some of his trophies.

“If you’re racing my kid and you need a motor, I’ll pull the motor off one of my other cars and give it to you,” Matt Johnson said. “And it’s happened for me. It’s happened for other parents. I’ve helped put motors and cars in between rounds that somebody gave them out of their car or trailer, just so they can make the next round.”

But none of this answers why any of them do it in the first place. Of course, it feels awesome to go fast and meet other people that also like to go fast, but there’s more to it than that for a lot of competitors.

“After racing, I was getting — not ego, but just happiness and confidence and the [knowledge] that I can do it,” Isabella said. “And then I get first place, and I’m like, ‘I can definitely do this. I can basically do anything.’ If only the girl who was driving and getting third could see me, her mind would probably blow up.”

CLICK TO MANAGE