After nearly 120 years in business, Sanders Funeral Home has closed. | Photo: Isabella Vanderheiden

###

Facing mounting financial losses, three local funeral homes abruptly ceased operations this month, leaving Humboldt County residents with just two options for local funerary and cremation services.

The closure — affecting Sanders Funeral Home and Humboldt Cremation & Funeral Service in Eureka, and Paul’s Chapel in Arcata — came just four months after workers formed an independent union, raising questions about whether the decision to shutter the facilities was driven solely by financial strain or influenced by tensions between the newly organized workers and out-of-state ownership.

In a recent interview with the Outpost, Guy Saxton, the Pennsylvania-based businessman who co-owns the three shuttered businesses, Ocean View Cemetery-Sunset Memorial Park, along with numerous other funeral homes and cemeteries across the country, emphatically denied claims that the decision to close had anything to do with the Humboldt Funerary Union.

“We were just hemorrhaging money with no reasonable prospect of ever becoming profitable,” Saxton said, adding that the businesses were losing between $20,000 and $30,000 per month. In December, those losses ticked up to $40,000 when several pieces of equipment broke at once. “Not only was it costly to repair, but we also had to send our cremations to Ayers. It was a disaster. … We considered two or three proposals to reorganize staff, but even those proposals didn’t have us breaking even. We would have still had to reinvest money to see if it was going to work, but there was really no path toward profitability.”

Asked why he and his business partner, John Yeatman, opted to close all three funeral homes at once rather than consolidating operations, Saxton said the facilities were all “run as one,” with most staff members working at all three locations. “And they were all losing money,” he added.

For decades — or in the case of Sanders, nearly 120 years — the three funeral homes provided local families with end-of-life planning and funerary services, ranging from traditional burials (the body is embalmed and buried in a casket, often with an accompanying ceremony) to direct cremation (the body is cremated without any viewing or funeral service). But traditional burials have been on a downward trend for decades as people gravitate toward more cost-effective options like cremation, which is often thousands — or even tens of thousands — of dollars cheaper than full-service ceremonies.

Data compiled in the National Funeral Directors Association’s “2024 Cremation & Burial Report” indicates that the U.S. cremation rate is “expected to increase from 61.9 percent in 2024 to 82.1 percent” by 2045. “The rising number of cremations can be attributed to changing consumer preferences, weakening religious prohibitions, cost considerations, and environmental concerns,” the report states.

Aubree Baker, former funeral director at Sanders Funeral Home and provisional president of the Humboldt Funerary Union, acknowledged the industry-wide shift toward cremation and shared Saxton’s concerns about the financial impact on local funeral homes, but felt those issues could have been addressed by smarter business practices and consolidation, not shuttering services.

“We agreed with the employer that, for example, Paul’s Chapel and Humboldt Cremation should close and that all of the business coming through there could be handled at Sanders … and offer competitive pricing in that model,” Baker told the Outpost. “There were a lot of other ideas that were brought up over the years … but the employer just kept pushing back and telling us we have to change the general price lists. … The costs of doing business have increased steadily over the years and we haven’t seen any increase in prices that would offset some of those additional costs.”

Some of these issues were what inspired Baker and other employees to form a union in the first place.

Forming the Humboldt Funerary Union

People who enter the death care industry aren’t in it for the pay. While salaries are generally dependent on experience and location, Google searches and online forums indicate that the average pay for a funeral director is comparable to a teacher’s salary. Comfortable, but not high-paying by any means. Baker entered the field, in part, because it gave more meaning to his own existence.

“It’s just something you’re drawn to. I’ve struggled with depression in my life, and while I was working with AmeriCorps doing removals as a kind of side gig, I had this renewed appreciation for my life,” he said. (In death care, removals refer to the process of moving a deceased person to a funeral home or other designated facility.) “Doing that work, being around death and being around people grieving really helped me — gosh, I’m getting sappy — appreciate the preciousness of life. It felt really comfortable to me to be in those types of environments and to help people through those moments.”

Megan Weshnak, former lead of operations and apprentice embalmer at Sanders Funeral Home and provisional vice president of the Humboldt Funerary Union, said her interest in the death care industry sparked when she was a teenager. Growing up in Los Angeles, the only air conditioner in the house was in her parents’ bedroom, where her mom had a collection of books about forensics that ignited an obsession.

“My parents were both at work during the summer, so I’d hang out in that air-conditioned room — they didn’t have a TV in there — and read these books by Patricia Cornwell,” she said. “The main character in the series is a medical examiner in Brockville, Virginia, and I just remember reading those books and being fascinated by the forensics and pathology — everything surrounding death investigation. And I was like, ‘I’m gonna do that! I’m gonna be the chief medical examiner at Quantico!’”

At the time, she didn’t realize how much schooling would be involved. She got into cosmetology after graduating from high school, but held onto her interest in death care. Years later, she found herself in a deep conversation with the embalmer for Paul’s Chapel.

“I just happened to run into her, and we had this hour-and-a-half conversation about all sorts of things. It ended with her saying, ‘I want to hire you,’” Weshnak said. “I started with removals, learning how to talk to grieving families and helping with daily operations. Eventually, I started the embalming apprenticeship, and I love it.”

“I do this because I can,” she continued. “It’s meaningful and it’s rewarding to me. So many people say, ‘I could never do what you do’, but I look at a Hospice nurse and say, ‘I can never do what you do’. Once someone is in my care, it’s about making that experience as peaceful as possible for the family.”

One of the problems with the death care industry, locally at least, is the lack of support for the people in it. Baker and Weshnak said they were driven to form a union to improve the “terms and conditions” of their employment, including increased access to mental health benefits and better pay.

“I think death care as a whole, not just in this particular company, is very underpaid. And there’s a significant mental health impact on the people that work in this field,” Weshnak said. “I don’t think the benefits really aligned with the needs of the people that worked [at the funeral homes]. … One specific thing we wanted to change was the pay structure for our removal staff. It was very difficult to get people to stay because it’s not very enticing work. In these negotiations, we were hoping to have removal staff paid in a similar manner as coroner’s on-call.”

While there are several trade associations representing funerary workers, unions are few and far between. Baker didn’t want to join a union representing a variety of trades, so he decided to create an independent union.

“We wanted to create something specific to us,” he said. “We know all of our issues and needs, so we felt it would serve us better if it were independent. That way, we would have control of it, versus having to put someone else in charge of our interests. The other thing is the timeline. We could be a lot more expeditious if we went independent rather than trying to affiliate and going through a whole process with an established entity.”

One of the first steps in establishing a union is gauging support. At least 30 percent of employees must sign the authorization cards before the proposal can be presented to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) for consideration. If more than 50 percent of employees sign authorization cards, the employer can choose to recognize the union without an election through the NLRB.

In September of 2024, Baker distributed the authorization cards and received signatures from a majority of employees. He shared the news with the business owner during a staff meeting and, later that night, sent an email to request formal recognition. The next day, he was asked to join a conference call with upper management.

“It was veiled as a sort of strategic meeting around some changes in business practices,” Baker recalled. “They said the businesses weren’t doing well, and they were having to make some changes to avoid continued financial loss. We felt that they were implying – or possibly threatening — layoffs or closure. A few days later, the owner [Saxton] showed up. He didn’t talk about the union, he just walked around and brought a friend over to look at the buildings.”

Baker said he hadn’t met Saxton in the five years he worked for the three funeral homes. During a subsequent meeting, Baker was informed that the company wasn’t going to voluntarily recognize the union, meaning the proposal would have to go through the NLRB process.

“They said, ‘We know you think that you should be in the union, but we think you shouldn’t.’ We’re just letting you know because that’s how we’re filing this petition,” Baker said. “Then we went through this intense nine-hour hearing with the labor board in November. … Long story short, the union was victorious in our hearing, and I was found to be eligible for union participation.”

“And then the smear campaign began,” he added.

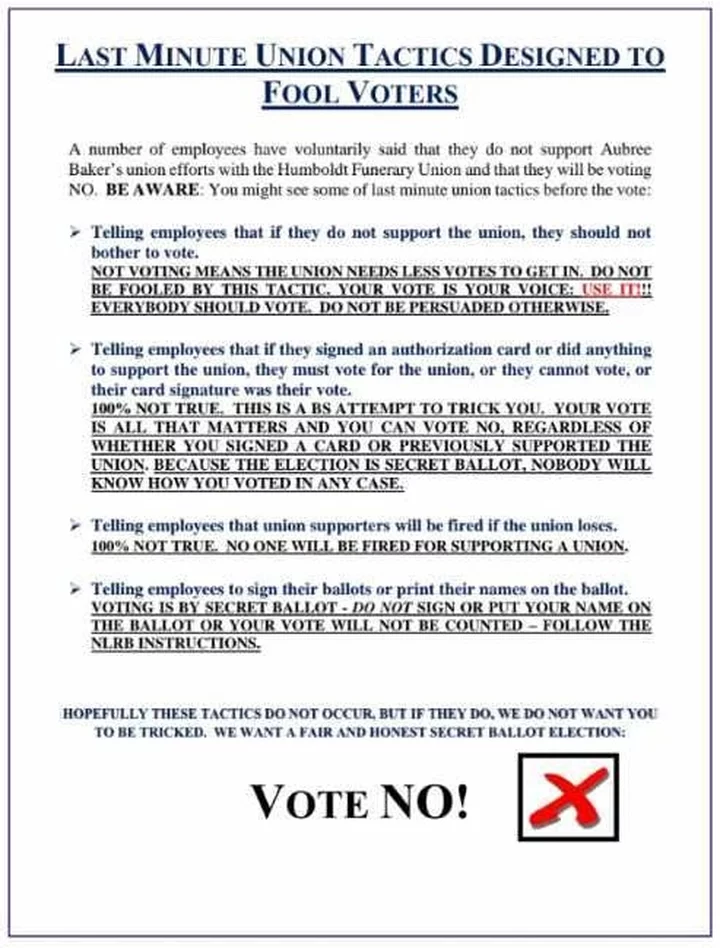

While employees waited for the NLRB to make a final decision, someone began distributing flyers containing misinformation about the aspiring union. The flyers alleged that Baker was attempting to fool employees and making false promises about the union.

Screenshot of one of the anti-union flyers.

“Aubree never said any of that,” Weshnak said. “It’s very strange that these are the things they’re putting in there. Tell people they cannot vote, or that their [authorization] card signature was their vote? That’s 100 percent not true. It’s just an attempt to trick employees.”

The smear campaign failed, and in mid-January, the NLRB certified the Humboldt Funerary Union. Over the next few weeks, the union started meeting and distributing educational materials to members. They started getting documents together for post-certification. “That’s when the company said they were going to lay people off,” Baker said.

The union fought back, arguing that the company couldn’t fire anyone because it would go against “status quo,” the agreed-upon terms and conditions of employment. “They can’t make any changes to our terms and conditions of employment without bargaining,” Baker said.

“We pushed hard,” he continued. “They presented their concerns and reasoning for wanting to do layoffs, certain financial goals they were trying to accomplish. And we replied with, ‘Here’s some things that we will do and some other things you can try. We project that if you do all these things, it would essentially meet your goals.’ They said, ‘No, we need to lay people off.’”

While union leaders weighed the pros and cons of standing their ground to “save as many jobs as possible,” the company started taking actions “to imply closure,” Baker said.

“They told all of us to stop ordering merchandise, to only sell off the floor,” he said. “We also heard from an employee at the cemetery that the funeral homes were closing. That communication was not happening with the union. So we asked, ‘Are you guys closing or not? We’re hearing rumors, and you’re acting like you’re closing.’ And they said, ‘We haven’t made a final decision yet.’”

Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act bars employers from threatening employees with adverse consequences, such as closing a workplace, if they support a union, engage in union activity, or select a union to represent them. However, it can be incredibly difficult to prove if a violation has occurred, especially if the issues predate the union.

“Whether or not an argument could be made, we’re a new, independent union. We don’t have money for legal counsel. How could we fight a complex case like this?” Baker asked. “The only last-ditch effort we had to save the company and everyone’s jobs was to relent on layoffs. We made a counterproposal that would preserve the financials. … A few days after we made that offer, they said they were closing all three funeral homes.”

I asked Baker and Weshnak if there was any indication that closure was imminent before unionization efforts started. Baker said he was aware that the company “was not terribly successful,” noting that there was a long-time manager who “was not attending to the financials as carefully and aggressively as they should have.”

During our conversation, Saxton maintained that the closures have nothing to do with the union, reiterating several times that the decision to shutter the businesses “was purely financial.” He said he wasn’t able to relay to the union just how bad the financial situation had gotten because of the “quiet period,” a term applied to companies in the process of going public. During a “quiet period,” companies must restrict certain communications and public information to ensure investors have access to the same information at the same time.

“It means that you can’t share information that might look like you’re trying to put your thumb on the scale or intimidate people to vote in a certain way,” Saxton said. “Once we got the request to unionize, I couldn’t come out and say, ‘Hey guys, just want to let you know we’re losing a lot of money.’ That’s not technically allowed. My understanding — I’m not an expert — is, at that point, you can’t really tell them because it could influence the vote.”

As soon as it was possible, Saxton said he shared financials with the union. At that point, he went over a few restructuring plans with the union but was met with resistance, due to proposed layoffs. “Even if we restructured, it was a Hail Mary to try to not lose money,” he said. “And eventually, we just ran out of time.”

Employees were informed of the impending closure around the beginning of April, and layoffs soon followed. As of this writing, the websites for all three funeral homes indicate business as usual. A call to each business was answered by polite people working for an outsourced phone service company who confirmed that the businesses were not accepting new cases.

Asked whether the businesses and properties were for sale, Saxton laughed at the question and asked if I had taken business classes or understood the value of a business.

“Would you buy something with perfect knowledge that into the future you would always lose money?” he asked. “No. We’ve listed the real estate at Paul’s for sale. I mean, if somebody wants to buy it and put a funeral home in there, they can do that. I’m told that that’s not the highest and best use for that property, and it’s going to probably end up being something else.”

Saxton said he intends to sell Sanders as well, though the property has yet to be listed.

Impacts on Remaining Mortuaries

The closure of the three funeral homes means Ayers Family Cremation and Goble’s Fortuna Mortuary will have to pick up the slack. Baker and Weshnak spoke highly of their former competitors but worried that the sudden uptick in cases could overwhelm their facilities.

“We handled over 500 cases a year between the three businesses,” Baker said. “Most of the death care in this community will have to be absorbed by the two other funeral homes, and it’s a huge impact. Not to mention that Sanders Funeral Home has been in business for over 100 years. It’s a huge loss to the community in terms of that legacy and all of the families that have used Sanders’ services over the years.”

Saxton said he’s been in contact with the owners about the closures and said he would be willing to help with transferring cases during the transition.

Reached for additional comment, Chuck Ayers, owner of Ayers Family Cremation, told the Outpost that his staff is preparing for a larger call volume and plans to expand some of their services to meet local demand. Ayers will take over some of the burial services that were previously provided by Paul’s Chapel. Goble’s will take over the rest, he said.

“I don’t think it’ll be drastic,” he said. “My understanding is that those three facilities [handle] less than 50 percent of local business. … It’ll be a substantial number of calls for us to take on, but not so much to overwhelm the two remaining mortuaries.”

The thing that keeps coming up, Ayers said, is concerns about prearrangements with the shuttered businesses. People who’ve prepaid for funeral or cremation services can have their arrangements easily moved to Ayers of Goble’s.

“We’re really getting the brunt of this frustration,” he said. “That money is safe. It doesn’t disappear with the closure of a funeral home. We can help transfer it, but there may be fees owed. It just depends on the case.”

The Outpost also contacted the Humboldt County Coroner’s Office about anticipated impacts associated with the closure. Sergeant Brandon Head said it’s difficult to determine the scale of the impact because the coroner’s office doesn’t keep tabs on each funeral home’s case volume, storage capacity or total cremation numbers.

If storage capacity becomes an issue, he said the coroner’s division would be willing to “help out where possible if decedents need to stay in storage longer than usual.” In 2024, his office conducted 350 death investigations, nearly 200 of which were determined to be natural causes. Another 400 deaths were reported to the coroner’s division in 2024, but did not require a full investigation.

“The severity of impact will depend on how the remaining companies adapt to the change and handle a likely increase in case load,” he wrote via email. “The remaining mortuaries offer a variety of services. I would hope the community still has access to what they need. It may just take a little longer to put their loved one to rest.”

The closure of the three facilities has hit Baker particularly hard. Not only did he lose the job he loved, but he also lost his on-site housing at the funeral home.

“I’ve lived there for over a year,” he said, noting that it’s common practice for funeral directors to live on-site to accommodate families in distress at any hour. “It’s not the company’s fault at all, but my personal financial situation is such that I may have to file for bankruptcy because of the sudden loss of income. The personal impact is really dire.”

Baker and Weshnak both expressed concerns about job prospects, given that they work in such a niche industry.

“I have a lot of different skills, but they’re all specific trades,” she said. “Could be an office administrator? No. Could I be a service advisor? Yes. Could I be a hairstylist? Yes. Could I work as a death care provider? Yes. … Not only that, but it seems everyone I talk to is getting laid off from their jobs right now. There’s a lot of people looking for work and not enough jobs.”

Neither Baker and Weshnak could say what’s next for their careers, but their dream is to open a new local death care facility that would offer alternative services and green burial practices, including green burials and human composting.

“That would be a huge benefit to our community,” Weshnak said. “We have all of these experienced death care professionals that work in death care for a reason. It’s a labor of love.”

CLICK TO MANAGE