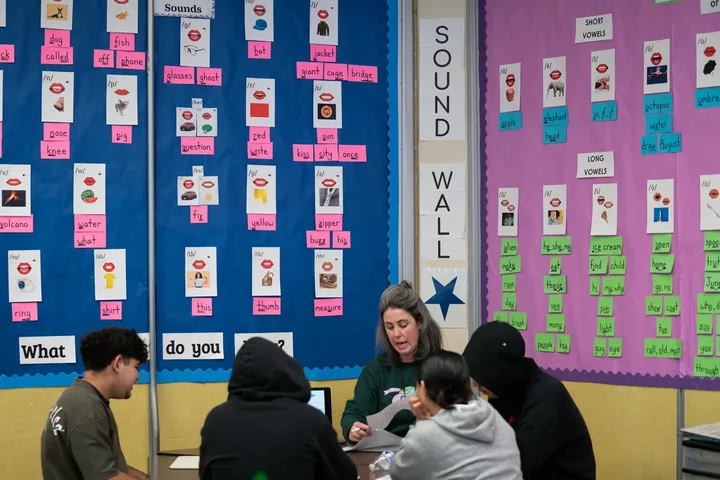

Teacher Katy Reese, center, works with students in a literacy class at Oakland International High School in Oakland on March 7, 2025. Photo by Florence Middleton for CalMatters

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

Can you spell deja vu?

The battle over the best way to teach children how to read has re-erupted in the California Legislature, as dueling factions haggle over a bill that would mandate a phonics-based style of reading curriculum.

The new bill, AB 1121, would require all schools to use a method based on the so-called “science of reading,” which emphasizes phonics. Last year, an almost identical bill died in the Assembly after pushback from the teachers union and English learner advocates, who argued that curriculum isn’t effective with students who aren’t fluent in English, and therefore shouldn’t be required.

The stakes are high, as California’s reading scores have stagnated since the pandemic. Nearly 60% of third graders weren’t reading at grade level last year, with some student groups faring even worse. More than 70% of Black and low-income students, for example, failed to meet the state’s reading standard.

The bill would build on existing legislation that requires credential programs to teach phonics instruction to teachers-in-training. The proposed legislation would require existing teachers to undergo training in the topic.

Assemblywoman Blanca Rubio, a Democrat from West Covina, who sponsored both bills, hopes this year’s version will fare better than its predecessor, even though it only contains minor tweaks from its earlier version.

“At this point, it’s personal for me. I’m termed out in four years and I want to get this done,” Rubio said. “Reading is such a foundational skill. We need to create the best opportunities for all kids to read, not just for those who can afford after-school tutors.”

Phonics vs. whole-language

The science of reading refers to research that shows reading isn’t a natural skill, like learning to speak. It must be explicitly taught, and the best method, primarily, is sounding words out rather than memorizing whole words by sight or trying to guess a word based on its context — an approach known as whole-language or balanced literacy instruction.

California schools use about half a dozen reading curricula, and some are more phonics-based than others. Typically, schools use a combination of programs and give teachers some leeway. Proponents of Rubio’s bill say that system makes it hard to track which reading curriculum works and can make it tough for students who switch schools, if the new school is using a different approach to literacy. That’s why the state needs a uniform reading curriculum, they said.

The California Reading Coalition, an advocacy group, surveyed 300 districts statewide in 2022 and found that 80% were using older curriculum that didn’t focus sufficiently on phonics. The report highlighted 10 districts that have large numbers of high-needs students but also had high reading scores — including Bonita Unified in Los Angeles County, Clovis Elementary near Fresno and Etiwanda Elementary in San Bernardino County. The districts use a variety of reading programs, but most have an emphasis on phonics.

Nearly 40 other states require phonics-based reading instruction.

“In other states, we’ve often seen governors and state education heads take the lead in driving these policies,” said Todd Collins, an organizer of the California Reading Coalition and former Palo Alto Unified school board member. “That would make a big difference for California — leadership from the top is crucial for getting good results. … We have a state-level reading crisis. State-level problems call for state-level action.”

Opposition from teachers, English learner advocates

The California Teachers Association, the union that represents 310,000 of the state’s K-12 educators, fought the previous literacy bill, arguing that teachers need flexibility in the classroom. So far the union has not taken a position on the new bill.

English learner advocates have fought both bills particularly hard. The California Association of Bilingual Education said the latest bill “fails to address the needs of English learners” and would cost too much money because it requires teachers to undergo training.

Students in a literacy class at Oakland International High School in Oakland on March 7, 2025. The school primarily serves students who are newly arrived immigrants and offers foundational literacy and English language development for its multilingual learners. Photo by Florence Middleton for CalMatters

First: A whiteboard with learning materials in a literacy classroom at Oakland International High School in Oakland on March 7, 2025. Last: Marcela Smith, center, an instructional assistant, works with students in a literacy class at Oakland International High School in Oakland on March 7, 2025. Photos by Florence Middleton for CalMatters

They also said that California already has a literacy framework and the state should do a better job of promoting that rather than introducing a new program altogether.

Students who aren’t native English speakers need a more flexible approach to reading, the group said. Reading programs that are heavily focused on phonics are too narrow and confusing for students who struggle with English, especially if they can’t understand what they’re reading, they said.

Martha Hernandez, executive director of the English learner advocacy group Californians Together, said the new bill is a “non-starter” unless it can include a broader approach to reading instruction, not one that focuses primarily on phonics.

English learners, she said, need schools to teach phonics hand-in-hand with oral language development and reading comprehension in a way that’s specifically suited to second-language acquisition. Prioritizing phonics gives short shrift to those other skills, she said.

“Literacy is multi-dimensional,” Hernandez said. “English learners need a more comprehensive approach.”

The bill has not yet been scheduled for a hearing, as both sides continue to work on a compromise.

Evidence of English learner success

Some districts that use phonics-based programs have seen good results with English learners and low-income Latino students generally.

At Kings Canyon Joint Unified, for example, English learners scored almost twice as high on reading tests last year as their counterparts statewide, according to the Smarter Balanced assessments. Almost half of low-income Latino students met the state reading standard, compared to 33% statewide. Kings Canyon, located in Fresno County, uses a curriculum called Wit & Wisdom, which is phonics-based.

Last year at Bonita Unified, near Pomona in Los Angeles County, which uses a phonics-based program called Benchmark, English learners scored nearly three times higher than their peers statewide. Almost 60% of low-income Latino students met the state reading standard, nearly double the percentage of their peers statewide.

Rubio was an English learner in California schools, and feels strongly that phonics is the most effective way to teach students who aren’t fluent in English. It can help them learn English vocabulary at the same time they’re learning how to decode words, a useful skill in any language.

“Reading is such a foundational skill. We need to create the best opportunities for all kids to read, not just for those who can afford after-school tutors.”

— Assemblymember Blanca Rubio

Yollie Flores, president of Families in Schools, an advocacy group that’s cosponsoring Rubio’s bill, was also an English learner in California schools. Literacy was a priority in her family, she said, in part because her father never learned to read. A laborer from Mexico who never attended school past third grade, he “worked his whole life, but couldn’t read a rental application, he couldn’t read basic instructions, he couldn’t read letters from our school,” Flores said. “He always told us, you must learn to read. It was very important to him — he knew that our ability to read would open our world.”

Flores is frustrated by the state’s persistently dismal reading scores for English learners — a situation that she believes could be improved with a phonics-based program.

“It is mind-boggling and disappointing and frankly, I find it harmful that (the California Association of Bilingual Education) would oppose something that could help all kids, including bilingual students, succeed in school and life,” said Flores, a former Los Angeles Unified school board member. “There is a vast body of research from the most respected reading scientists in the world telling us one unequivocal truth: there is a specific, evidence-based approach to teaching children to read. I struggle to understand why they are fighting it.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom hasn’t taken a position on the bill, but has been a strong supporter of literacy generally. He championed a screening test for dyslexia, which will be given to all kindergarten-through-second-graders starting this fall; approved funding for 2,000 literacy coaches to work in high-needs schools; and fought for transitional kindergarten for all 4-year-olds, which is intended to boost students’ reading skills.

Over the past few years, the warring factions of the literacy battle have found common ground, publishing a pair of papers that essentially call for a truce. In the papers, both sides agreed that English learners have unique needs when learning how to read, and any formal policy or curriculum should address those needs. They also agreed that both sides should dispense with labels and over-simplifying the various approaches to reading instruction, and look at the issue with more nuance.

The truce doesn’t seem to have reached the Legislature, though. So far, English learner groups remain opposed.

‘Unlocking something’

At Oakland International High School, a public school for recent immigrants, nearly all students are English learners and a majority read at a kindergarten level when they enroll. That’s because they’ve had little formal education in their home countries or their schooling has been disrupted, in some cases for years.

International flags hang in the cafeteria as the courtyard is reflected on a window at Oakland International High School in Oakland on March 7, 2025. The school primarily serves students who are newly arrived immigrants and offers foundational literacy and English language development for its multilingual learners. Photo by Florence Middleton for CalMatters

But teachers there use a phonics-based approach that’s tailored to English learners, with good results. A student will learn to sound out the word “hop,” for example, while seeing a picture of a person hopping, then spell “hop” and read “hop” in a passage. They learn to connect the sound of a word with its meaning.

“When they start to see the patterns and rules, it starts to make sense and they get excited,” said Aly Kronick, a literacy teacher at Oakland International High for the past 10 years. “It’s like they’re unlocking something. They feel successful.”

She said the process can be slow, but within two years students go from minimal literacy skills to reading whole passages with high levels of comprehension. Some students have even gone on to four-year colleges. One student went on to become a bilingual teacher. Others have returned to the school after they graduated to lead phonics instruction in the classroom.

Rachel Hunt, a parent in Los Angeles Unified who’s a former teacher and school principal, has been a proponent of phonics-based reading instruction. She noticed firsthand the importance of a good reading program when her family moved from Massachusetts to California about eight years ago. Her child, who uses they/them pronouns, was in second grade when the family enrolled them at an elementary school in Los Angeles County that was using a phonics-based curriculum. Although her child was reading at grade level, they struggled with the ability to identify sounds, which affected their spelling skills.

“They were so behind in that regard,” Hunt said. “They felt so self-conscious. Other kids would call them ‘stupid.’ They developed a lack of self-esteem which was really damaging.”

Her child eventually caught up and is now a sophomore at Eagle Rock High School near Glendale, where they’re an avid reader and doing well.

“If you see that a majority of kids aren’t reading at grade level, and we know that explicit (phonics) instruction works, it seems obvious that this is something we should be mandating,” Hunt said.

CLICK TO MANAGE