Ted

Ruprecht’s Obituary

August 1, 1928 to December 14,

2024

The best life stories are the ones the person writes himself. This is excerpted from an essay our father wrote for his 80th birthday celebration. We celebrated again on his 90th, and he continued having adventures until past his 96th. Here’s what he wrote:

###

I was born to Lorraine Follet & Fredrick Kilian Ruprecht in New York’s Presbyterian Hospital. My grandfather migrated alone from Germany at 16 years old and rose to became head of the Standard Oil maritime division. My mother was the first female Art Director of a New York advertising agency. My father quit college to go to sea on a Standard Oil ship. He became a naval architect.

I grew up in Brooklyn a sickly child, as evidenced by having to repeat the first grade and my memory of taking cod-liver oil and having to sit by the window to absorb sunlight. I remember my first fight on the streets of NY, which I lost. That night my father gave me a boxing lesson and the next day out I went to restore justice with my first fight victory.

Our apartment was next to the baseball field in Prospect Park. My father and I would go up to the roof and watch the games. Thus, was born my enjoyment of baseball. I became a lifetime fan of the Dodgers.

When I was seven, my parents wanted to get me and my sister out of NY and so we moved to Ardsley, a small Italian community about 25 miles north of the city that was settled by Italian workers brought to the US to build the NY Aqueduct.

We lived a few miles from town in the country. I loved it. My activities were gardening with my father, sledding in the winter where you belly-flopped immediately after another kid, sledded faster, reached out, grabbed and jerked his runner and sent him into the snow bank.

Christmas was very important in our family. We never saw the tree until Christmas morning. This was during the Depression, and I found out later that my father waited until Christmas Eve when the trees were cheaper to buy it. I slept very little on Christmas Eve because I knew Santa was going to give me a kiss and I was afraid his beard would tickle me and wake me up and if I woke there would be no Christmas. In the morning, I would lead a family parade through the house and by the tree and presents while singing “O Tannenbaum.”

In about the third grade, I began to notice I couldn’t see the blackboard but I didn’t want to wear glasses, so when we lined up at school for our eye exams, I memorized the eye chart—which worked fine until they asked me to read it backwards.

During the Great Depression, when there was no war on and no need to build more naval ships, my father was laid off. My mom was the primary breadwinner. We moved frequently because we were living in foreclosed houses. Eventually the bank would sell that house, and we’d move to another. By the fifth grade we were in Crestwood, still 25 miles from NY, along the Bronx River where we lived in a 3-story Victorian house with sliding doors, a curved staircase and a tower. I had the entire third floor with my electric trains in the tower. Lots of kids to play with, learned to ride a bike, had my first girlfriend, and put in a big flower garden with my father.

During the summers, we spent a week at a relative’s farm in Vermont who took in visitors to augment their farm income. We kids watched the cows being milked; we slopped the pigs and jumped in the big hay pile in the barn. Thus, was born my desire to live in the country and have animals.

During WWII, my father came out to California to design cargo ships being built in Long Beach. When times seemed safe, he brought the rest of the family west to Long Beach, California, the summer before the seventh grade.

I was painfully shy. Back East in the summer, we wore shorts, but when I did this in California the neighborhood kids made fun of me. The result was I never again went outside to play for the rest of the summer. I gardened and made balsa plane and ship models and miniscule clay ship models.

Despite the sickly childhood, I never had an absent day in Jr. High, mostly because I didn’t know what the process was to return to school after missing a day and was too shy to find out. I remember air-raid warnings and blackouts with our heavy black curtains and boxes of sand to put out the incendiary bombs. In Junior High I did all the athletic activities and got my first exposure to track in the All-City Jr. High track meet. When we tried out for it at school, I ran a sprint but they sent me back to try again because they said I wasn’t trying; they hadn’t seen me straining. I was trying, I just ran relaxed, and I was not yet very fast.

At Woodrow Wilson High School, I went out for track. My father had run middle distance in college and my mother had gotten her nickname Coy from the star university football player noted for his speed. For the first workout, we all lined up to run a quarter mile race. I had no clue, but toward the end I began passing gobs of people so I was entered in the ‘B’ 220 at our first meet. I got second, and the couch came and said, “Give this kid a uniform,” as I had run in my gym clothes.

As a Junior, I won the All-City 440 in probably the most significant race of my life because coming toward the end I was very tired (I was always very tired, always throwing up after each race) and in third place. I remember thinking, “I can just coast in and nobody will ever know,” but I decided not to, to give a final effort in what I now consider a momentous life course decision. As a senior, I was elected captain and ran the sprints, set the school record in the 220, was selected All-City, got second in both sprints, was selected in the So-Cal Interscholastic Federation, placed in the state meet, and had the ego-stroking experience of being recruited for college.

I chose Occidental College (Oxy) mostly due to the guidance of my high school teacher, Vince Reel, who was a graduate from Oxy. He was also a great coach, being selected by the US Dept of State to coach three different countries’ Olympic teams, an important element in my maturation. My Oxy coach was Payton Jordan, himself a great sprinter and later a US Olympic coach. The two most memorable track events of college were first, anchoring the meet that decided the final relay in Oxy’s dual most victory over Stanford University, and second, the four man mile relay in my junior year in the Coliseum Invitational before 40,000 spectators.

Because this was an invitational meet, teams were from all over the US. The favorite, Morgan State, was a black team from the East Coast with three National Collegiate Champions-to-be. We were invited as a sort of local flavor afterthought. In a neck and neck race, Oxy won in the fastest time in the world for that year and the second fastest winning time in history.

I aspired to be a naval architect like my father, but he advised against it. He said it was only a good profession when there was a war on.

While working on my Ph.D in Economics at UC Berkeley, I continued to run. My first year at Berkeley was an Olympic year and I tried to make the Olympic team. I did run my personal best time, and although I didn’t make the team, my time would have qualified me for every other country’s team except Germany.

I had culture shock when I went to large and impersonal Berkeley from little, sheltered Occidental. My appointed advisor was a famous economics theoretician, but I never met him, he was too busy; my advising was done by the secretary.

During my third year, I was the “house mother” in one of the dorms, and I noticed a cute switchboard operator wearing a low-cut dress. I sought her out at the first “mixer” dance. Later, when I got down on both knees and asked her to marry me, Joan Marie Ledgerwood made my life by saying yes.

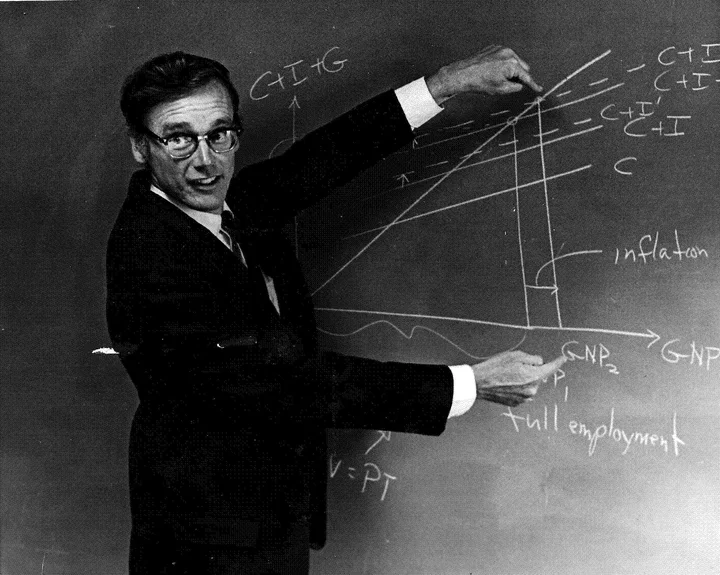

I left Berkeley to teach at Occidental while I continued to work on my dissertation, “Population Growth and Egyptian Economic Development.” As a graduate student, I published a paper in the prestigious American Economic Review.

We had our first child, Janet, in Los Angeles. When we came to Humboldt State College in 1958, there were only two economists and a student body of 2000. I intended to stay 3-4 years as that was how to play the academic game, but ended up staying 33 years — until retirement.

During this, time we added Carol, Phillip and Elaine to the family and spent considerable time abroad on various leaves.

The was a Fulbright research grant to the Philippines to continue working on the issues of rapid population growth’s impacts on economic development. I had the privilege of working with one of the all-time greatest demographers, Frank Lorimer, who became a mentor and promoter for me. The year spent there was exciting, with terrific collogues, breakthrough research and eventually a book on the subject, as well as collaboration on a Philippine Economics textbook, a number of papers and conference presentations in the Philippines and at the world population conference in Belgrade, Yugoslavia.

Sadly, we lost a second son, Luke, in childbirth in the Philippines.

The Fulbright experience later led to an invitation to be a member of an elite International Labor Organization team to go to the Philippines and prepare a study on Philippine economic development for the government. President Marcos invited the team to breakfast at the palace, where I ate the best mangos I’ve ever tasted.

The family spent 15 months in Paris, France, while I was a consultant to the Organization for Economic Co-operation & Development and its Population Center. All our children went to French school and learned French without previously knowing any at all. Another book was one outcome of this very interesting experience in a large prestigious international organization.

I spent a term as a visiting scholar in the Demography Department of the Australian National University in Canberra. Later, with support from the Population Council in New York, I served for a summer as advisor on population to the Koran Development Institute in Seoul. Where, among other things, I learned to hate kim-chee.

My colleague at HSU, Frank Jewett, and I developed a computer program that allowed us to examine the effect of demographic change at the family economic level in contrast to the common macro economic level. One result of this work was to be invited to contribute a chapter to a book edited by the French demographer, Leon Tabah, for the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, the leading world organization for population study. Frank Lorimer, one of its past presidents, nominated me for membership and into I was admitted. A second result was an invitation to present some of our findings at an international conference in Tunisia, a paper and discussion of this and others’ papers that had to be done in French. A third result of our work was the publication of the book, The Micro-economics of Demographic Changes.

The final international academic experience was another Fulbright, this time to the Karl Marx Institute of Higher Economics in Sofia, Bulgaria in the Fall of 1992. What made this rather extraordinary was that I was the first western economist after the change from communism to be at this University, which was the elite economics university in the country. I taught in English to the best and most eager students I ever had. In fact, I had teacher’s shock when I got back to HSU due to the contrast and decided to retire.

In Sofia, I enjoyed interviewing the people selling goods in the street market. They were avid entrepreneurs.

During my years at HSU, I gained a reputation as a very hard grader. One of my students famously said, “I worked harder for this C than any other grade I ever got.” Notwithstanding, I was selected HSU’s Outstanding Professor by the student body.

I was careful never to serve as the Economics Department chair, as this was a thankless task. But I did serve as president of ACSCP, the forerunner of the Academic Senate. I retired in 1993, as did Joan.

Years later, a former student, Don Lewis, who had become an economics professor at the University of Wollongong in Australia, honored me by funding a Research Assistanceship at HSU. I remembered him well: he came to office hours to discuss an exam and I asked him his major. He replied, “Athletics.” He wanted to become a football coach. I said, “What a waste.” This casual remark changed the trajectory of his life.

Travel was an important part of our retirement. Joan and I traveled in the Caribbean, cruised from Manous, Brazil, to Senegal, Morocco and the Mediterranean, and around South America from Chile to Argentina, and across the Atlantic to Europe and the Baltic countries, and to 34 ports in the Norwegian fjords. Later we cruised to Mexico, Hawaii, and Alaska.

During the running boom of the 70s, I returned to running locally with the Six Rivers Running Club, and also in the combined running and horseback riding discipline of Ride & Tie where Joan and I, and later my daughter Carol, competed in the world championships—of which I completed 25. Overseas I competed in Australia in the Canberra Times Championship 10 Kilometer and in the Blagoevgrad Half Marathon in Bulgaria. I also competed in Endurance Horseback Riding, which involves long distance, usually 50 miles, cross-country races. I accumulated 12,000 race miles.

The nicest things ever said to me were:

1) yes, I will marry you, by Joan to my proposal,

2) you ride like a 13-year-old girl,

And 3) you passed your Ph.D qualifying examination.

###

Our dad lived another 16 years after writing this. He doesn’t mention his extensive vegetable and flower gardens, for which he is justly famous. Or that he and our mom helped raise their grandson, Louis Ruprecht, and greatly enjoyed their other grandkids, Sara (Howard) Landrum, Jessica Ruprecht, Kate (Ruprecht) Rust, who are now raising the great-grandkids. He also served as a mentor to Robert Yarber, who lived with our family for six years, and Slavena (Savova) Castle, who as a teenager befriended them in Sofia and returned with them to continue her education in the States.

He was active in the Ride & Tie Association, serving as a board member and the treasurer, as well as managing two World Championships in Humboldt County. He also served as a board member and treasurer for the Redwood Empire Endurance Riders.

He was a fierce warrior to protect the greater Trinidad area from development. He was a founder of Save Rural Trinidad and a board member of the ensuing Trinidad Coastal Land Trust. He granted an easement on the Ruprecht Ranch property to the Trust in order to keep it rural forever.

The family would like to express our gratitude to Shelly Luna and Jaime Sumahit, who helped lovingly care for our parents.

Because we held a big birthday celebration in August for both parents, the family is not planning a celebration of life at this time. If you can, please send a memory by email to janet.ruprecht@gmail.com.

If you are so inclined, you may make a donation to the Dr. Ted Ruprecht Research Assistantship in Economics for students involved in research with an Economics faculty member, by choosing Fund ID: A6687 at this link. Or mailing to the Gift Processing Center, Cal Poly Humboldt, 1 Harpst St, Arcata, CA 95521. Please note “In Memory of Ted Ruprecht” in the memo line.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Ted Ruprecht’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

CLICK TO MANAGE