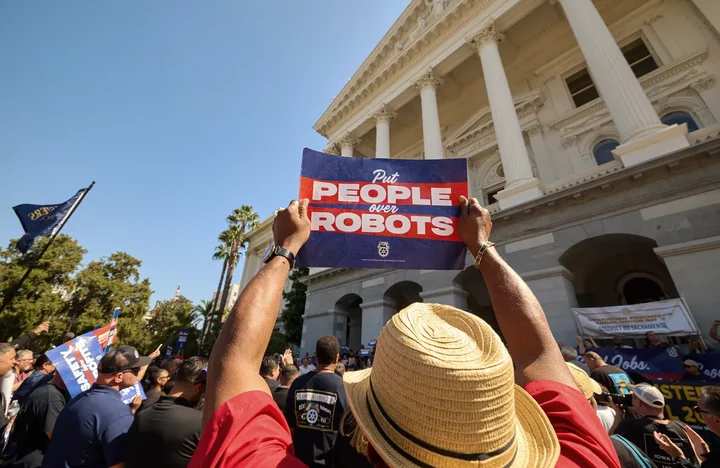

A protester holds a sign on the steps of the state Capitol calling on Gov. Gavin Newsom to sign a bill that would require a human operator in all autonomous vehicles in Sacramento on Sept. 19, 2023. Photo by Fred Greaves for CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

The bill was dead. Twice dead, in fact: Two times in the past two years, Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed legislation to ban California companies from deploying driverless trucks.

Yet lawmakers have resurrected the idea and inserted it into a new bill — with the Teamsters union hoping the third time will be the charm.

There’s no indication Newsom has changed his mind. Still, Democratic Assemblymember Cecilia Aguiar-Curry, representing the Davis area, said she brought the autonomous trucking bill back because it’s good policy aimed at “protecting our public safety and our jobs.” She said it has nothing to do with the Teamsters’ large donations to lawmakers.

Assembly Bill 33 is an example of a phenomenon in the California Legislature: Even when a bill dies one year, and even if a governor kills it, there’s a strong likelihood it will return, especially if big money interests like labor unions and business groups want it signed into law.

A CalMatters analysis using the Digital Democracy database that tracks the more than 2,000 bills introduced this year found at least 80 measures that are similar – some identical – to legislation that Newsom or other governors have vetoed in previous years. Around a quarter of the resurrected bills had support from prominent labor groups; an almost equal number were backed by business.

CalMatters relied on the Legislature’s bill analyses to determine whether a measure had been vetoed before. If a previous veto was not noted in the bill analysis it wouldn’t show up, meaning the figure is likely an undercount. The analysis didn’t tally the dozens of other resurrected bills pending in the Legislature this year that already died before reaching the governor’s desk.

The previously vetoed bills tackle issues large and small including dangerous cigarette lighters, prevailing wage, jury duty for probation officers, colorectal cancer screenings, reproductive health care access, groundwater use at duck-hunting clubs, statewide guaranteed income, newspaper ads and environmental, labor and social justice measures.

The number of failed bills returning year after year helps fuel one of the Legislature’s most troubling issues. The massive number of bills introduced each year contributes to lawmakers rushing through the democratic process and fosters a culture of secrecy at the Capitol. As CalMatters reported, lawmakers routinely silence members of the public during hearings in order to jam through the huge volume of bills. Lawmakers also regularly make their decisions behind closed doors, in part because there is so little time to debate their hundreds of bills in public.

Experts say that doesn’t necessarily mean bills shouldn’t come back after failing. Some good ideas take time to gain political support. Alex Vassar, a legislative historian at the California State Library, noted that it took decades of failed legislation to pass laws that eventually built the state’s highway system and that gave women the right to vote.

“You can keep an issue on the front of the public’s mind, keep it alive in Sacramento, by using the vehicle of the bill to advance conversations happening outside the capital,” said Thad Kousser, a former California legislative staffer who’s now a political science professor at UC San Diego. “Sometimes, it’s part of a longer-term strategy to move policy forward.”

‘Not here to serve the lobbyists’

The Teamsters union is a major funder in the California statehouse, contributing at least $2.7 million to lawmakers’ campaigns since 2015. Aguiar-Curry received at least $15,950 in campaign cash from the Teamsters and its affiliate unions in that time, according to the Digital Democracy database.

But she said that didn’t influence her decision to try again on autonomous trucking.

“I’m not here to serve the lobbyists,” she said.

Aguiar-Curry said she hopes that tweaks she made to the latest legislation could appeal to Newsom, who has tended to be friendlier to Big Tech companies than legislators are to big labor. The latest proposal would prohibit driverless trucks from delivering commercial goods directly to a residence or to a business, instead of barring all driverless trucks over 10,001 pounds as in previous legislation. Newsom’s press office declined to do an on-the-record interview for this story.

Assemblymember Cecilia Aguiar-Curry, representing the 4th California Assembly District, speaks at a protest led by The Teamsters calling on Gov. Gavin Newsom to sign a bill that would require a human operator in all autonomous vehicles at the state Capitol in Sacramento on Sept. 19, 2023. Photo by Fred Greaves for Cal Matters

“The governor’s veto messages speak for themselves,” his spokesperson, Izzy Gardon, said in an email. “And our office does not typically comment on pending legislation.”

Citing polling that shows Californians are leery of fully autonomous trucks, supporters say that if Newsom vetoes it again, they’ll just keep bringing it back until he signs it – or until the next governor does.

“We’re right on this issue,” said Peter Finn, the Western region vice president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. “The only person that’s wrong on this issue is the governor, and just because one person is choosing Big Tech over people and drivers doesn’t mean we should stop pursuing this issue.”

This year’s bill easily passed the Assembly floor on Thursday with only a handful of Republicans voting “no.”

Doctors again fight private equity

Business groups, meanwhile, are pushing at least 20 other bills that Newsom or other governors have vetoed.

A prominent example is Senate Bill 351, co-sponsored by the California Medical Association, which lobbies on behalf of the state’s physicians. The organization wants to regulate private equity groups and hedge funds when they try to buy medical and dental practices.

Last year’s legislation sought to give the California attorney general power to block the sale of health care companies to for-profit investors.

In vetoing the measure, Newsom said it wasn’t necessary. This year’s bill doesn’t go as far, but it contains nearly identical language that would prohibit investors from “interfering with the professional judgment of physicians or dentists in making health care decisions,” according to the bill’s analysis. The measure also would allow the attorney general to sue if an investment firm violates the rules.

“Private equity firms are gaining influence in our health care system, leading to rising costs and undermining the quality of care,” Erin Mellon, a spokesperson for the medical association, said in an email.

CMA has given at least $3.5 million to legislators since 2015, according to Digital Democracy. The doctors lobby also has donated at least $9,500 to this year’s author, freshman Democratic Sen. Christopher Cabaldon, the former mayor of West Sacramento.

Cabaldon said in an interview that he introduced the bill because it’s about “taking care of the patients.”

“Doctors and other health care providers,” he said, “are leaving their practices, or in some cases, leaving the industry altogether, because their ability to practice as clinicians and deliver the best possible care has been under threat by overly aggressive private equity operators who are putting the profits first.”

Cabaldon’s proposal passed the Senate last week with Republican opposition.

Lawmakers bring back passion topics

While wealthy groups push for their favored bills to come back, other pieces of legislation return simply because a lawmaker is passionate about the subject matter.

That’s why Assembly Republican Leader James Gallagher, who represents the Chico area, reintroduced a bill Newsom vetoed last year that would have given families legal authority to visit loved ones in health care facilities during pandemics. Gallagher said he hated not being able to visit his dying aunt during the Covid-19 outbreak.

“It’s wrong, man, especially if it’s a loved one,” he said.

Newsom vetoed the first measure, saying that California’s pandemic visitation policies struck the right balance, and he was concerned Gallagher’s bill would “result in confusion and create different access to patients.”

Gallagher’s newest version of the bill didn’t get a hearing this year.

For Assemblymember Tom Lackey, a Republican representing the Palmdale area, it bothers him that victims of the 2020 Bobcat Fire in his district have to pay state taxes on settlement payments they received from the power company whose lines started the fire.

“It’s brutal,” he said. “I mean, ‘Here’s your money to try to restore yourself, but, oh, by the way, you can’t have it all. We want some of it back.’ … It’s a second kick in the mouth.”

It’s why he reintroduced a settlement tax relief bill this year after Newsom vetoed it last year along with a number of other similar bills.

Lackey said he hopes his latest bill is unnecessary. Newsom noted in his veto message that the settlement tax provisions “should be included as part of the annual budget process.” Newsom’s proposed budget this year includes tax breaks for some disaster settlements. Lackey hopes that will include the Bobcat Fire.

Social justice bills come back

Other previously vetoed bills seek to address social justice issues that are important to lawmakers. They include proposals to create anti-discrimination awareness campaigns, putting non-English language accent marks on government forms and diversity audits for gubernatorial appointees. Newsom has vetoed “substantially similar” diversity audit bills six consecutive times.

Democratic Assemblymember James Ramos, representing the San Bernardino area, is the Legislature’s first Native American member. He believes that California’s first peoples have been silenced and marginalized for too long.

It’s why he’s authored two bills that have been previously vetoed. One would remove requirements from school administrators to approve the cultural regalia students wear at graduations. Former Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed a similar bill, saying “principals and democratically elected school boards” should decide what’s appropriate to wear. Another previously vetoed Ramos bill seeks to expand tribal police forces. He’s also a co-author of a previously vetoed measure seeking to provide resources to locate missing Indigenous people.

Ramos said he applauds Newsom for doing more than other governors have to apologize for the historic harms done to Native people, but more work needs to be done.

“When the state became a state, they did not include the voices of California’s first people,” he said. “So these bills do a lot more than other bills in the Legislature. These bills educate, and they move forward for reckoning and atonement.”

Should Newsom decide to veto Ramos’ bills again – or any of the others he or other governors have previously killed – it’s unlikely lawmakers will push back.

As CalMatters reported, nearly all of the 189 bills Newsom vetoed last year had support from more than two-thirds of lawmakers — a threshold large enough to override the governor’s veto.

But that almost never happens. The last time the Legislature overrode a governor’s veto was in 1979 on a bill that banned banks from selling insurance.

###

Digital Democracy’s data analysis intern, Luke Fanguna, contributed to this story.

CLICK TO MANAGE