Joan

Ledgerwood Ruprecht

July

24,1934 to February 25, 2025

It all began innocently enough. Joan Marie Ledgerwood was born to Mary (Creel) and Howard Ledgerwood at the University Hospital in San Francisco. She may have been tiny, but she would become a Force of Nature.

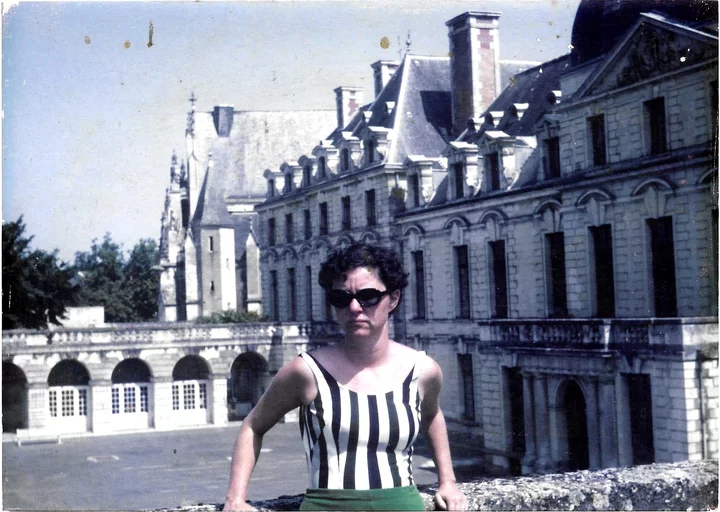

Our friends and family love to tell Joanie Ruprecht stories. Let’s just begin with this picture, our father’s favorite. It was taken about 1969, while the family spent a year in France, and our mom still looks stunning after five pregnancies.

In her childhood dreams, she flew on her winged white horse. When the horse grew tired, they landed, and Joan opened a cabinet in his belly to pull out her tool box and make repairs. She wanted to be a vet when she grew up.

She was an intrepid adventurer, riding when she rode buses alone all over San Francisco as a child. After the family moved to Soquel, she and her dog rambled in the mountains, just the two of them.

During World War II, like all the other kids, she collected scrap metal and purchased a War Bond. She and her brother Jim loved the Lone Ranger Movies at the Saturday Matinee. One morning after the war, all the Japanese kids returned to school, and Joan was shocked to realize she hadn’t even noticed they were gone.

She was a teenager when her dad and his friends went hunting for gold in the Los Angeles hills. Her mother got a phone call her mother got from the morgue asking where to send the body. This was the first Mary knew he had been killed. Howard had been down inside a mine shaft when the rope broke and the bucket of rocks hit him on the head. His so-called friends went on the lam. This terrible phone call haunted Mary all the rest of her life.

Joan was a senior in high school, playing tennis with a girlfriend, when a complete stranger stopped tell them if they maintained B averages, they could go to college anywhere. Because women weren’t allowed in to vet schools in the 1950s, Joan chose UC Berkeley and Public Health.

The summer before college, she worked as a scab while the switchboard operators were on strike. Afterward, at Berkeley, Joan worked the switchboard in the dormitories. One day, while wearing a low-cut dress, she attracted the attention of a graduate student who was working as “housemother” in the international dorm. Ted Ruprecht invited her to a dance. And that was the beginning of their 70 years of romance.

Ted was six years older, and Joan’s roommate asked why she was dating “that old man?”

Perhaps the roommate didn’t yet know what we all have learned. The quickest way to get our mom to do anything was to tell her she shouldn’t.

Ted proposed on both knees.

She once told me her wedding night was the happiest moment of her life. The morning after, her new husband told her he had just been laid off his job because the shop was closing. Luckily for him, she was used to the idea of unemployed husbands!

After graduation, Ted taught at his alma mater, Occidental College, and Joan worked at the Los Angeles Public Health Department. They were saving up for a European vacation when she accidentally got pregnant with me, Janet. She had no regrets: Europe could wait.

Ted’s second teaching job was at Humboldt State College, when he was still ABD (All But Dissertation). These two “city kids” rented property that allowed them to have a milk cow, rabbits, chickens, ducks, a dog, and ultimately a pony. And then two more kids: Carol and Phillip, at two-year intervals.

This job was supposed to be a stepping stone in Ted’s academic career, but instead he and his colleagues decided to stay and make something of the tiny Economics department. The Ruprechts bought 20 acres north of Trinidad where they could be ‘gentleman farmers.” Joan applied her laboratory skills to pasteurizing milk, raising hens for eggs, and plucking the roosters for the dinner table. At night, they continued work on the dissertation on the kitchen table: she typed, while he cut and pasted.

When our mother was still a blushing bride, she hardly knew any swear words, and she remained vague about some of the meanings. One night, she announced at a faculty party, “Ted says the dean is a real cocksucker.”

You could have heard a pin drop.

Our father thought it wise to get out of town for a while. He applied for a Fulbright Research Fellowship in the Philippines, and he and his wife and their three kids got aboard a ship in San Francisco. We explored every port of call.

Our mother was pregnant with their fourth child. The birth was bungled, and the baby boy was born dead despite an emergency c-section. Mother just about lost her mind.

Then our three-year old brother Phillip was diagnosed with tuberculosis. In those days, the United States would not have allowed him back into the country. Fortunately, a second test proved negative.

After they returned to California, they began to clear pasture on the homestead. The preferred method was to stake out a goat to trim the branches, next a pig to root, and then the kids to drag brush uphill (it was always uphill) to Mother’s glorious bonfire. The pigs especially got loose a lot and came trotting to the house for handouts. Eventually, they got too big to hold with rope and ended up in the freezer. Meanwhile, all the kids inherited the pyromaniac bug.

After her electric cookstove broke down, Mother declared she wasn’t going to waste $500 on a new stove. Instead, she spent $500 on a refurbished wood-burning stove. We all learned to cook on that stove.

Joan loved to go to the animal auction. Once she bought Carol a tiny pig: it got loose in the car, squeezed under the back seat, and ended up under Mother’s feet and the brake and gas pedals. She was infamous for time she bought a heifer that jumped out of the back of the pickup on the highway. And for the bull she set loose in the pasture; it jumped out and bred the neighbors’ prize cows.

She was desperate to have a baby to replace the one she’d lost in the Philippines, and she gave our father an ultimatum: no more sex unless they were going to make another baby.

This time, her doctor told her, she would have to have another Caesarian. The plan was to wait until she started going into labor, so the birth would be as near natural as possible. But when her time actually came, the doctor was out of town. Mother was furious.

In those days, laboring women were given a medicine that acted like truth serum. Enraged, she kept asking, “Who got me into this?” Who, indeed?

When the doctor finally arrived, she told him exactly what she thought of him in some pretty raw language until at last Elaine was born.

Our dad got a research grant at Yale, and our parents decided to camp across Canada to get to Connecticut. Mom bought a very second-hand station wagon that her mechanic declared he would not trust to drive as far as Eureka. She hand-painted it brown and cream, named it Brownie, and loaded up her four kids. But first, she tied jingle bells to toddler Elaine’s shoes, in case she wandered out of camp in bear country.

That winter, she took us to every church in that Connecticut village so we could be exposed to all the denominations and enjoy the architecture. Our dad had been an altar boy, but our mom must have been raised outside the church. Not knowing any better, she instantly swallowed the Communion bread and wine.

She took us to museums. The way I remember it, she and Phillip would set out for the dinosaur display while I made a beeline for the Ancient Egyptians, and who even knows where Carol and Elaine got to? Mother taught us the joy of owning art by taking us to the gift shop and letting us each choose our favorite reproduction.

This was the sixties, and Mother decided she wanted to adopt another baby. She wanted to contribute to racial integration, but not being savvy about changing norms, she enraged a Black woman by saying she wanted to adopt a “Negro” baby. After the explosion, she chickened out.

On our way home, travelling across the South, she taught us about Jim Crow laws and racism by taking us to the “Colored” toilets. In Atlanta, she and our dad went to pay their respects to the newly assassinated Martin Luther King.

We had barely returned to Trinidad when our dad was recruited for a year-long consultancy at the prestigious Organization of Cooperation and Economic Development in Paris. Mother decided the best way to cross the United States with four kids was by travelling at night by Greyhound and skiing at resorts in the daytime. Not our dad: he took an airplane to New York. I should have gone with him.

We spent a very long, cold night shivering in a VW Bug in the parking lot of a ski resort because we were caught in a snowstorm. The lodge was locked tight and ours was the only car in the lot.

When we got to Paris, our rented house was not ready, and we holed up in the Hotel Confort. Mother took us to the American Library and unaccountably left us behind to be retrieved later—except that the library closed before she came back. We kids had to navigate the Metro back to the hotel. In the days that followed, she refused to get out of bed or eat. This was our first exposure to what in those days was called manic depression.

Our parents dumped us in the French school because “total immersion” was all the rage in education. The French teachers did not make us welcome. However, Mother made up for it by taking us on bike adventures or exploring the underground fortress in the woods that no one in our village would talk about. She enrolled Carol and me in Ballet and horseback riding, and Phillip in Judo. She said we should learn how to fall.

She was a tease. One evening, she secretly prepared horsemeat for dinner before one of our riding lessons? Fortunately, she did not admit to this crime for years.

After we returned from France, she bought a half-starved Arabian mare, Faratha. Upon the advice of friends, we fed her all the grain and alfalfa she could eat. The mare became crazed and spooked at everything, yet who put her girl children on its back and sent us out into the world?

And who — after I had been dragged after the saddle slipped sideways, knocked unconscious, and later decided to give up horses forever — went right out and bought a second mare? Because Mother had driven the car, I had to ride the horse home. As a logging truck passed us, I prepared to die. But gentle Felina didn’t turn a hair. Slowly, my love of horses returned.

While I was away at college, Felina was stolen out of a locked field. Mother searched everywhere. She went to the auction with Felina’s photo and discovered the sheriff’s deputy who was supposed to be looking for her didn’t even know what color she was. My mare was never recovered, and once again I gave up horses forever.

Years later, she bred a grey mare to a brown stud. When the mare’s belly muscles tore internally so badly that they couldn’t hold up the foal, Mother and two friends created a girdle with a pack saddle to cinch her belly up and let her carry the foal to term. When the miracle baby was born alive, and as red and white as my lost horse, Mother said, “Here’s your new Felina.”

One summer, our dad went to Korea for a summer. Mother took it into her head to surprise him in Manila. All her friends advised against it. So of course, she went. Boy,was he surprised when he got into the hotel elevator and there she was.

She didn’t tell him she had taken up running while he was away because she was feeling depressed. She just took him to Clam Beach and ran away from him. Our dad had been a world class sprinter in college; he was furious about his decline. He took up running again.

She entered the Clam Beach Run. She discovered Ride & Tie, a sport in which two people take turns running and sharing a horse. While looking for an easy marathon, she ran the Santa Cruz Sky to the Sea fifty miles downhill all the way. She rode her first 50-mile Endurance Race. She dragged our dad into these sports.

Mom taught us that the best way to get a job is to volunteer. While her last child, Elaine, was in elementary school, Mom volunteered at the Health Department. Soon she was working full time, and ultimately became the head of the Laboratory.

Our mother was an early expert on the tick-borne Lyme’s Disease and went to international conferences. At the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, the public health nurses, fearful of contamination, refused to draw blood for AIDS testing. Our mother did it. She tested for other sexually transmitted diseases. She tested rabid bats and foxes. She also tested oysters from the Humboldt Bay. She was expected to dispose of them afterwards. Instead, she brought them home and declared them delicious.

During a Grand Jury inquiry, Mother testified that funds earmarked to upgrade the lab equipment were being spent elsewhere by the county administrators. The lab funding was restored.

The County administrators used to hire hatchet men every so often to clean house. One tried to force Mother out. She fought tooth and nail, claiming workplace-related mental health stress, until finally there was a compromise and she was allowed to honorably retire.

My parents spent another summer in the Philippines and Australia, this time with Grandma Mary and three of the kids. As a young married student, I stayed home and thus missed the incident in which Mother insisted on visiting an infamous prison. The inmates wore bright orange jumpsuits. Orange was Mother’s color. She really wanted a jumpsuit. She offered to exchange her blouse. If not for the guards preventing the trade, she would have stripped it right off.

Our dad received another Fullbright Fellowship, this time to teach capitalist economics in Bulgaria at the Karl Marx Institute right after the fall of communism. Our mom was stalked on the bus and down the street by a teenager who finally got up the courage to introduce herself and ask if she could practice her English. This was Slavena Savova. Mother later moved heaven and earth to get the State Department to grant a visa so Slavi could come live with the Ruprechts while she attended American high school.

One of her proudest accomplishments was the First Annual Hoopa Hike. Using logging maps, she, our father, our teenaged brother, our friend Bob Dickerson, our live-in college student, Bob Yarber, and his dog, Willie, hiked four days from Hoopa to Trinidad. They were propelled by the force of her sheer willpower — which was substantial. There has never been a Second Annual.

At retirement age, our parents both became full-time athletes. They competed in Ride & Tie and Endurance all across the western United States. Mother persuaded our dad that breeding horses was a terrific tax dodge. You could lose money in the horse business for seven years and write it off.

She traded a dog for a white Arabian mare that had foundered. This was Feather. Our mom bred her (of course) and brought her back from lameness to be competitive over 50-mile races. She said Feather was her dream horse from her childhood. Although not quite winged, Feather couldn’t be slowed, and Mother would ride at speed down a narrow forest path calling, “I can’t stop her!” This did not make her universally admired.

One summer, I came home to find a single-horse trailer parked in their forest. I recognized it immediately as a declaration of her independence. I feared their marriage was over. But I was proved wrong.

When my first husband, Jeff, was dying of cancer at age 25, my mom came to help. She loaded him, me, and the wheelchair into our Pinto, and took us to the beach. We got Jeff, who could barely walk, into the waves and he laughed aloud as he rolled back and forth.

I moved home again after he died, and Mother offered to take me to Mardi Gras in New Orleans, but I suggested we go to Carnival in Rio instead. She took all three daughters. In the back of beyond, our rental car broke down, and while I assumed we would be raped and murdered, she taught us that you can always wave down a trucker for help.

Later that night, she shared a bottle of red wine and a packet of kids’ photographs with the woman who was renting us a room in her house. Without a word of common language, they talked all night in the language of friendship.

After my sweetheart, Paul, followed me home to Trinidad, my brother and his wife moved in. Not very many grown children could have lived as happily with their parents as we did. However, denied grandchildren, Mother went into a breeding frenzy. In addition to breeding horses, she would trawl her bitch in heat through Trinidad, hoping to find a handsome father for the puppies.

This continued until my teen-aged sister surprised us by becoming pregnant. Mother’s breeding efforts abruptly stopped. For a few years, all the adults in the household raised the baby, Louis.

In retirement, our parents took classes in the Over 60s program at HSU. Mother frequently left her keys in the door or the ignition or the lock of her car trunk when she went to class. Eventually, the car was stolen. This car was of great sentimental value because our father had given it to her. By the time the police recovered it, the car had been stripped of everything, including the wheels. Mother was slowly restoring all the missing parts when four wheels of exactly the right make were advertised in the Tri City Advertiser. Joan bought back her own wheels, identified them by the serial numbers of her tires, and turned the evidence over to the police. No one was ever arrested.

My own husband became a Fullbright scholar, and we went to live in Germany while Paul did his Ph.D. research. My parents brought our friend Betty, Grandma Mary, and Elaine and her boyfriend to visit. Grandma Mary was determined to visit Toledo, Spain, before she died. My mother was determined to visit a colleague who had retired from the lab in Finland. My husband patiently tried to explain this was impossible. He spread maps across the floor to show them the train routes. He calculated the distance and time. He was wasting his breath.

Mother and Grandma Mary traveled from Germany to Toledo to the Artic Circle and back in five days. They were triumphant.

After she got home, Mother discovered a slug race to be held at Patrick’s Point. She had admired the deep orange slugs in our forest in Germany. She told us to send her one for the race. Even though we knew we were breaking international laws, such was the force of her nature that we dutifully packed up a slug and a spare in a metal tea box and sent them to Trinidad. By the time they arrived, they had turned a sickly grey and they performed poorly. Mother released them into the wild. Of course she did.

Mother was intuitive, perhaps psychic. On the night her father died, he appeared to her in her bedroom. Years later, as our sister Elaine prepared for her wedding, Mother had a very bad feeling about the officiant. He was a former Catholic priest turned Episcopalian and he did not approve of weddings held outdoors in a field instead of a sanctified church, nor of having children stand up with the bride and groom, nor of horses in the ceremony. Clearly not the right priest for a Ruprecht wedding. After the pre-marital counseling, he took Jim aside and recommended calling off the wedding because he thought Elaine was not ready to commit. After a sleepless night, Jim decided they needed to find a new officiant.

Luckily, Mother had seen this coming. She had secretly lined up a judge who loved having the bride ride up on horseback and the children serve as bridesmaids and groomsmen.

In retirement, Mother taught dozens of girls to ride. She recruited 10-year-olds and took them on adventures into the deep woods. She also had a soft spot for grown women who had always longed to ride but had never had the opportunity. She introduced her friends to Endurance and Ride & Tie. She and our father became leaders in the local clubs and helped put on competitions in the Redwoods.

Everywhere Mother went, she took her dogs. She was famous for loading them into the trunk of her car. She rode with a succession of hounds — to protect her from bears and mountain lions — and small dogs who thought they were hounds, including a Pomeranian, a chihuahua mix, and something shaped like a Shi-tzu.

All was not sweetness and light. Horse clubs are very contentious. In one of the biggest conflicts, our local club divided sharply between the lovers of dogs and the despisers of dogs, especially in Ride Camp. Especially loose dogs in camp.

Did I note that the quickest way to get her to do something was to forbid it?

On one notable occasion, when dogs were outlawed from a local ride, she reserved a family campsite outside Ride Camp and sent her grandson Louis with a whole pack of dogs to stay there. Except the dogs saw Mother across the campground and came running to greet her. Things got ugly with Ride Management.

Our parents took up cruising. They treated the ships like floating hotels, and they travelled all over the world, including Antarctica and the Norwegian Fjords. What they liked most was the social aspect, and toward the end, they cruised to Mexico, Hawaii, and Alaska, not really caring about the destination.

Whenever I asked for advice on life, Mother answered, “Have fun.” And if you weren’t having fun, she advised you to something different. Joan Ruprecht lived her life to the utmost, and although there was tragedy as well, she most certainly had a great deal of fun.

Our mother was an extremely lucky person, and she knew it. She was scary behind the wheel, but I was willing to get in the car with her because I knew she was incredibly lucky.

She never quit marveling at how lucky she was to marry our father. Last summer, we celebrated their 96th and 90th birthdays. Our father passed peacefully this last December, and after 70 years of true love, Mother was lost without him. Although her memory was failing, she never forgot her beloved. Most of the time, she knew he was gone, but she still called out for him in the night. After two and a half months, she followed him to wherever he’s gone.

They are still having adventures.

Once again, the family would like to thank Shelly Luna and Jaime Sumahit for their tender care of our parents.

We will hold a joint Celebration of Life on August 2nd at the Ruprecht Ranch.

I am putting together a book of the Joanie stories we love to tell, but I’m sure some great ones have yet to written down. Please email me at janet.ruprecht@gmail.com or call me at (707) 407-6258 and tell me your favorite. Maybe I can wedge it into the book.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Joan Ruprecht’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

CLICK TO MANAGE