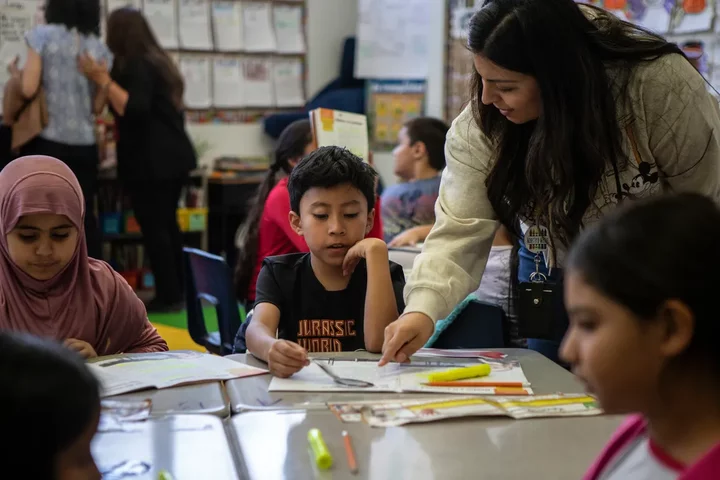

Students at Washington Elementary School in Madera on Oct. 29, 2024. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

In his first year as governor, Gavin Newsom made the creation of a comprehensive, statewide education data system one of his top priorities, but its debut is behind schedule.

In 2019, he launched the Cradle-to-Career Data System, a multi-year initiative to collate data from preschools, K-12 districts, colleges and job training programs, culminating in a series of public dashboards that track students’ progress. A few years later, during his 2022 re-election campaign, “cradle to career” was the tagline of his education platform.

“This was a signature initiative by the governor,” said Alex Barrios, the president of the Educational Results Partnership, an education data nonprofit. “You’d think taxpayers would be asking: “Where is this thing?’”

The Cradle-to-Career team initially said the public would have access to some of the data by the spring of 2024, mostly through a website that would show the progress of specific school district students through college and their first few years of employment. Later, the Cradle-to-Career team updated the timeline to say that the data would be publicly available in the fall of 2024. Now, Angelique Palomar, a spokesperson for the data project, said the first data dashboard will be publicly available “this spring,” though she did not specify a date.

Palomar said the first stage of the project is nearly ready for release and that the delays stem from an abundance of caution regarding students’ privacy. For example, she pointed to certain populations, such as students in rural areas or certain racial/ethnic groups, which are so small that it’s easy to figure out someone’s identity. Federal law prohibits schools from sharing students’ personal data.

“We are prioritizing securing the data system, ensuring privacy protections, and providing linked information that is accurate and reliable before we can make our tools publicly available,” she said.

The state’s Department of Technology, which periodically reviews IT projects, says the Cradle-to-Career Data System needs “immediate corrective action” because of its delayed schedule.

Once it’s released, the Cradle-to-Career data system could reshape parents’ and students’ decisions and lead to significant policy changes. With this data, parents would be able to see the long-term college and employment results of their child’s local elementary school district. School and college counselors could provide more precise advice to students about their futures, and state programs, such as the under-utilized savings program CalKIDS, could use the data to pinpoint potential beneficiaries.

Lacking an adequate data system

Before the launch of Cradle-to-Career, California was “one of only a handful of states without a student data system that can answer important questions about the educational pipeline and the impact of education on work and earnings,” a report by the Public Policy Institute of California stated in 2018.

Kentucky’s data system already allows for that kind of analysis and is the “canonical” example of good education data, said Iwunze Ugo, a researcher with the institute. He acknowledged California’s progress since the 2018 report. “The Cradle-to-Career system in California is particularly notable for how ambitious it is.”

Since 2019, the state has allocated more than $24 million for the project. The Cradle-to-Career Data System became an official state entity, with a 25-person team, 21 board members, and two, 16-member advisory boards. Ugo pointed out that unlike other states, California has made “community engagement” a centerpiece of the data tool: The state embarked on a multi-year campaign, surveying communities in both Spanish and English across the state about potential uses and concerns with its data and the way it will be presented.

Cradle-to-Career has signed data-sharing agreements with 16 other state agencies, such as the California Department of Education and the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency, and processed over a billion data points about students’ education and workforce outcomes.

At a February board meeting, the Cradle-to-Career staff shared a progress report, outlining over 20 accomplishments, each with a check next to it. The only blank box in the checklist was the last one: officially launching the first data dashboard.

In his opening remarks, Cradle-to-Career Board Chairperson Gavin Payne didn’t acknowledge the delay — none of the board members did, overtly.

Mary Ann Bates, executive director of the Cradle-to-Career Data System, referred to the delay briefly in her remarks to the board, saying that her office is committed to releasing the first tranche of data and “looking at all options to hold the contractor accountable” for “some delays and lost time.” Asked by CalMatters to clarify the comments, Palomar, the spokesperson for Cradle-to-Career, said Deloitte is the contractor, but she refused to specify why it may be responsible for these delays.

Could the data be ‘used against’ school districts?

Although unprecedented in scope for California, many of the features of the Cradle-to-Career Data System aren’t new. The data already exists, albeit in some hard-to-find places, and some groups have already started working together to analyze shared trends.

Barrios’ nonprofit, the Educational Results Partnership, has received over $13 million since 2012 to help create and operate Cal-PASS Plus, which allows users to see how students from specific California high school districts perform at the college level. But Cal-PASS Plus is only available to researchers as well as school and college administrators, and most K-12 districts are not required to participate. Still, in any given year, Cal-PASS Plus has records from more than 70% of high school students in the state, Barrios said.

A mandatory data-sharing system, such as Cradle-to-Career, is harder to implement, he said. “School districts don’t want the data used against them.” For example, he said one fear is that residents and policymakers might blame a high school for a low college matriculation rate instead of working to improve it. Palomar said the current delays are not tied to any reluctance by school districts since the data already exists and is shared widely.

Barrios said his organization stopped operating Cal-PASS Plus a few years ago, in part because he assumed it would soon be obsolete.

“We walked away from all these things thinking the state was going to do it,” he said. “But that obviously hasn’t happened.”

CLICK TO MANAGE