Aryay came to Humboldt County, like many others, to live out some of the visionary propositions

of the 1960s. He had so far been rewarded with beatings, arrests and a fat file in the offices of

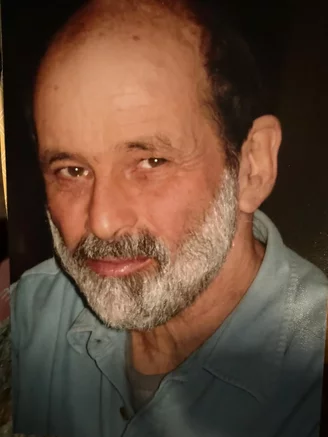

the FBI. His photo had made the front page of the San Francisco paper when HUAC (the House

Unamerican Activities Committee) came to town hunting for commies and subversives. Sprayed

by fire hoses along with other protestors, cops dragged him feet first down the marble stairs of

city hall’s rotunda, hands jammed in the pockets of his corduroy jacket, looking like he was

exactly where he wanted to be.

Even as the child of a liberal and cultured Portland family-he began violin at an early age-he reacted badly to unreasoned authority. Sent to a pre-eminent eastern college, he left during his first year with an allergic reaction to the prevailing idea of order. Only after living a year with relatives in Berkeley, who introduced him to leftist living and found him a job driving a furniture truck — beautiful music and working class politics-did he begin to find his way to health and happiness.

He enrolled at UC Berkeley, studied history, and joined SLATE, the political group that preceded the Free Speech Movement, introducing politics to the “quiet generation” of 1950’s college students, around issues like racial discrimination-yes, in Berkeley!-as well as apartheid in South Africa, atomic bomb testing but also mandatory ROTC and the segregation of women at UC football games.

From college he went east again, working for the National Lawyers Guild as an organizer wherever his skills were needed — in the Jim Crow south, north again, then back to the west coast where he worked with the Farmworkers under Cesar Chavez, and with the Panthers in some of their early organizing around breakfasts for children and the armed defense of neighborhoods.

All these now-famous actions attracted increasing violence during the Vietnam years, from Nixon’s dirty tricksters to hard-hat goons, leather-wearing bikers, and from trigger-happy cops and national guardsmen. This repression created strong solidarity on the left, but it was also met with hardening dogma and an all too familiar authoritarianism.

It was time to move to the country.

Aryay began half a lifetime of work on an old house in Manila, he started an organic garden, supported himself by knife sharpening and carpentry-and he continued to be a political organizer wherever a social ill presented itself. In mid-century America, spraying toxic herbicides had become a chief tool of forest management, highway maintenance, and yard care, and it spoke personally to anyone with allergies. Aryay and his partner, Ann-Marie Martin, worked as co-chairs of Humboldt Herbicide Task Force, and under their leadership this practice-so widely accepted as to appear “normal,” never to be questioned-turned out to be deeply unpopular with a huge swath of the public, from Native basket weavers to nursing mothers, from health workers to farm workers. Organizing is never finished-many of these toxics are still permitted-but now in Humboldt County there are rules and regulations in place. You can still see the signs in front of rural houses: NO SPRAY.

A decade later, still in Manila, Aryay and a hand-picked group of activists began a campaign against off-road vehicles that were destroying its dunes and threatening the peace and safety of the community. Again, off-road driving was an accepted activity (Ronald Regan declared it a national form of recreation) affecting only some low-value hills of sand and a fewlow-income people. But organizing begins with asking questions and when people were queried at the mall and grocery stores, it was true that they didn’t care as deeply as they might about their poor neighbors and endangered wallflowers, but they really, really wanted dune buggies off their beaches. And when they formed a coalition, and held it together for years of protests and meetings, people got their property, their personal safety, and their beaches back.

These contributions to community well-being, and many others, smaller and quieter, were never Aryay’s end goal, not what he was most proud of. When he was in hospice and wrote his own brief obit, he mentioned none of that. It was his home repair, small jobs for people of modest means-he’d place an ad in Senior News-along with his organic gardening, and especially his composting that he listed among his chief accomplishments. In musical quartets and on remodel jobs, while bowling and engaged in friendships were his greatest pleasures, most especially with long-time companion and wife,Marcia Brenta and her two children, Amelia Hughes and Mario Brown. Aryay celebrated community in their home in Bayside, honoring day of the dead and solstice for many years. He embraced excursions to Breitenbush,Oregon and Rubio, Smith River for process and rejuvenation. Aryays loud gutfaw-hawl when something struck his funny bone, was a reminder of his delight in good company.

But when he saw the need for change in our lives, he was on us. From our most private moments-to his last breaths he argued for the efficacy of the compost toilet-to the most dire challenges of sea level rise, he was organizing us like lost sheep. In his final days in hospice, his letter to the editor appeared in the Mad River Union.

“The people who survive the coming changes and challenges will have to live closer to the Earth, from [off] the Earth, and with each other.” Like a good organizer, he told those people (maybe you) to ask questions: “Questions about what of the industrial culture can be salvaged, and for how long, will be important to ask.”

Thanks, Aryay. You will be missed.Our VERBEENA. Aryay will be remembered by many family and friends in Portland, Humboldt, Berkeley, San Anselmo and Santa Rosa.

Celebration of life will be held at the Humboldt Unitarian Fellowship

24 Fellowship Way, Bayside, CA 95524

June 7th

5-8 pm

RSVP

707-601-4687

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Aryay Kalaki’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

CLICK TO MANAGE