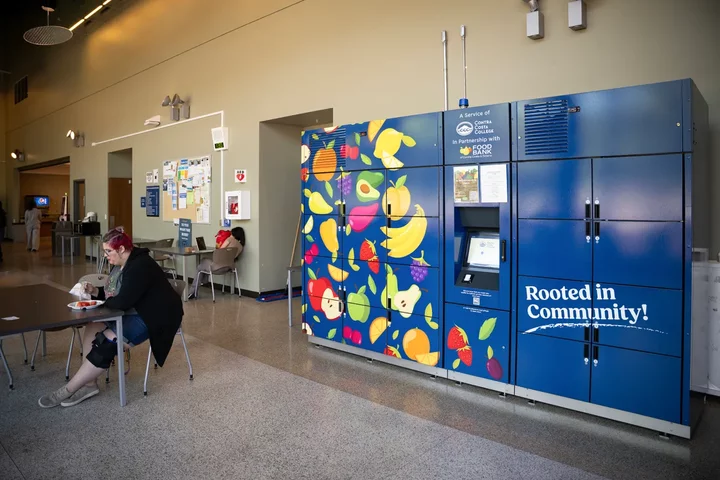

Teddy Thollaug eats at the Contra Costa College dining hall in front of the refrigerated food lockers in San Pablo on May 8, 2025. Thollaug works as a student worker at the campus’ Basic Needs Services, which offers weekly free food to low-income students through the lockers. Photo by Florence Middleton for CalMatters.

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

Since 2022, California has been offering free lunches to all students in elementary through high school. But once they reach college, more than two-thirds of students experience food insecurity.

The federally funded CalFresh program feeds some college students, but the complicated application process and eligibility rules prevent many from accessing funds. More than 70% of eligible students don’t receive CalFresh, according to a 2024 California Policy Lab report.

To improve CalFresh outreach and enrollment, California started setting aside annual funds in 2021 for public colleges and universities to establish and operate basic needs centers with food pantries, where students obtain free food staples. The California State University and University of California systems each receive $15 million and California Community Colleges receives $30 million annually. As of 2023, every public higher education campus in the state has a basic needs center and food pantry.

However, for many campuses, these solutions still aren’t enough. To fill the gaps, some have created their own innovative solutions. From free meals to food lockers, staff and students at five campuses around California offer creative alternatives.

Humboldt students level up their food pantry

At Cal Poly Humboldt, through the full-service food program “Oh SNAP!,” students stock the shelves, fill pantry orders and offer CalFresh application support. They also greet their peers as they enter, offering them tea or coffee.

To reduce food waste, students negotiated in 2016 with the campus dining services department to collect unused food to offer at the pantry at no cost to students. The department notifies the basic needs center when leftovers are available; students bring their own containers to package up what they need.

Oh SNAP! has hired a local organic farmer to provide produce and give classes on cooking and gardening. The program also offers pop-up thrift stores where students can fill a bag with clothes and housewares for $5; proceeds go back into the program.

Oh SNAP! “provides peace of mind,” said Anna Martinez, a student studying political science, law and policy at Cal Poly Humboldt. “I don’t have to really worry too heavy on whether or not I can afford food, because if I can’t, there’s always Oh SNAP! I can go to.”

As the social justice, equity and inclusion officer for Cal Poly’s student government, Martinez successfully advocated for the student board to increase funding for cultural foods. She values the sense of community Oh SNAP! provides.

“They’re very welcoming when it comes to different needs,” she said.

The program, vital for the 6,000 students at Cal Poly Humboldt, clocked 30,000 visits to Oh SNAP! last year, according to Mira Friedman, health education and clinic support services lead.

Compton College serves free meals to all

Sara Goldrick-Rab, a Philadelphia sociologist and advocate for college student basic needs, thinks a free meal every day is “exactly what is needed” on college campuses. She conducted a study giving students free, daily meals for three semesters at Bunker Hill Community College in Boston.

“It allowed students to eat in a regular way in the school cafeteria, just like they would in the National School Lunch Program. And lo-and-behold, it increased graduation rates,” Goldrick-Rab said.

Compton College President Keith Curry read about the Bunker Hill pilot program and decided to implement a similar program at Compton. Now, every Compton student — and employee — receives a daily meal. Students also get $20 each week to spend at the campus farmer’s market. Students enrolled in CalFresh receive $50 each week for the farmer’s market and can use their EBT card at campus dining services. The college uses a mix of grants and various campus funds to cover the costs of the meal program.

“We’re doing more than any other community college in the state of California and also nationally,” Curry said. “How many schools can say that students receive one meal per day on their campus from their cafeteria?”

The Compton College campus in Compton. Photo via Compton College

Some California colleges offer a limited number of free meals, such as UC Davis, where a food truck serves between 300 and 400 meals per day and students pay what they want. In fall 2025, West Valley-Mission District in Santa Clara County will begin offering free meals.

Student Corinthia Mims said the first time she entered Compton’s cafeteria, “it was joy, always buzzing,” she said. Her twin, Cynthia Mims, said the free meals bring everyone together like family.

“[Students] feel embraced and they feel important. It’s a feast,” she said.

Feeding students keeps them in school. According to data the college gathered last year, students who received free meals and money for the farmers’ market were more likely to stay in their classes for the entire semester with a completion rate of 1% or 2% higher than the general population.

Curry visits the cafeteria to get feedback from the students. “They’re proud to tell me what they like and what they got today. Because there’s no negative stigma around it, because everyone is treated equally,” he said.

Goldrick-Rab highlights the program at Compton College as an example of what a college student universal meal plan could look like. “It’s a very nice modern version. … It’s not really a cafeteria in the classic sense. It is refrigerators full of prepared meals, the way that adults would go into a Whole Foods and get a grab-and-go,” she said.

In 2019, U.S. Sen. Adam Schiff, a Democrat from California, introduced the Food for Thought bill, which proposes universal meal pilot programs on college campuses. The bill failed and was reintroduced in 2022 and 2023 but never enacted.

Contra Costa College fills food lockers with free meals

At Contra Costa College, students who work full time have difficulty accessing the food pantry during open hours. In April, the college unveiled 20 refrigerated lockers in the campus cafeteria where students can pick up their pre-ordered, free groceries between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. Monday through Friday. Students order online and student staff fill the orders.

The campus basic needs center, called the Compass Center, also offers free meal vouchers to students three days a week, giving out 50 for breakfast, 75 for lunch and 15 for dinner.

Teddy Thollaug, a first-year student studying art and journalism at Contra Costa College, says they appreciate the hot meals and food lockers, especially on days when their disability makes it too hard to stand and cook. Because Thollaug’s classes are all online, they are not on campus regularly.

Teddy Thollaug at the Contra Costa College dining hall in San Pablo on May 8, 2025. Thollaug works as a student worker at the campus’ Basic Needs Services, which offers weekly free food to low-income students delivered through refrigerated food lockers in the dining hall. Photo by Florence Middleton for CalMatters

A typical order includes fresh fruit and vegetables, butter and cheese, and a “mystery package,” which contains grains, sauces and canned food. “Honestly, I feel like a kid on Christmas every time I open a mystery package,” Thollaug said.

In 2024, the center served 5,008 students and 14,785 families of students, according to Hope Dixon, the basic needs center coordinator.

Antelope Valley College students earn points for food

To encourage and support students to take full course loads, Antelope Valley College initiated Fresh Success, a CalFresh program that “pays” enrolled students in points for enrolled units.

Full-time students get more points, “because that’s our goal. We want you to get your degree, and [if you’re a full-time student,] you’re less likely to be able to run around and get all the other community resources,” said Jill Zimmerman, dean of the Antelope Valley College student health and wellness center.

Fresh Success is part of CalFresh’s Employment and Training program, and is overseen by the Foundation for California Community Colleges. Currently 20 colleges across 18 counties participate in the program, which partially reimburses schools with federal dollars for workforce development services such as job training and job search assistance for low-income students.

Fresh Success allocates points for each unit enrolled, up to 40 points per week. Students use their points at the on-campus pantry to purchase food, toiletries and laundry soap.

For Alliza Wade, having access to Fresh Success means being able to put more time toward school rather than working more hours. Wade, a STEM major at Antelope Valley College, is enrolled in CalFresh but it doesn’t cover all of her food expenses.

“[Fresh Success] has a very, very significant impact on how I’m able to live and eat, and how I’m going to be able to pursue my future, because [it helps with] saving and being able to eat healthy,” Wade said.

Since the college is reimbursed 45 cents for every dollar spent, the Fresh Success program benefits the college as well by providing funds to put towards employment and training support like job-specific clothing and gear, cooking classes and car tune-ups through the campus automotive program.

Cerro Coso feeds students who aren’t eligible for CalFresh

When Lorena Moreno started as the basic needs coordinator in early 2024 at Cerro Coso Community College in the southeastern Sierra region of the state, she noticed that students without permanent legal status were in dire need of assistance. Non-citizens are not eligible for CalFresh.

Moreno tackled the need by creating an on-campus food program called WileyFresh — modeled on Aggie Fresh at UC Davis, which serves students who meet CalFresh requirements but lack citizenship. Eligible students receive a monthly Albertson’s gift card valued at $291, comparable to the amount an eligible single student receives on a monthly CalFresh EBT card.

Like the Aggie Fresh program, students who qualify for WileyFresh are required to participate in workshops that support academic and personal growth. Moreno offers the workshops as a webinar to protect student identities.

The Cerro Coso Community College in Ridgecrest. Photo via the Cerro Coso Community College

Last fall, Moreno increased outreach efforts. Her team of part-time student employees passed out flyers at events to raise awareness. They saw visits to the Wiley Food Pantry grow from about 350 per month in the spring semester to about 500 per week in the fall.

This summer, Moreno intends to expand the program to include more students who can’t enroll in CalFresh. “Because at the end of the day, that’s what it’s intended for — this population who is missing out.”

Research shows students can’t rely on each other’s charity

Many colleges now offer a way for students to donate unused card swipes from their campus meal plans to each other. However, research shows that these donations only reach a tiny fraction of students.

Before 2017, college dining services did not allow students to share their meal plans with other students. This didn’t sit well with students at Morehouse and Spelman colleges in Atlanta. They began a hunger strike to challenge meal plan policies that forbid sharing meal swipes. Their activism convinced their colleges to change the policies and led to a nationwide program, Swipe Out Hunger.

Meal-swipe programs, as they’re called at the approximately 850 colleges nationwide that offer them, allow students to donate unused meal swipes to fellow students who need them. In California, 17 colleges participate in Swipe Out Hunger.

But they are not effective, Goldrick-Rab said. She evaluated Swipe Out Hunger and found that the active programs see just 300 swipes a year.

“At the bottom line, I would rather give people money than food, but I still think the National School Lunch Program is important. I just want all of it. I want the guaranteed basic income. I want a higher minimum wage. Because all of it is scientifically working,” Goldrick-Rab said.

###

Amy Moore is a fellow with the College Journalism Network, a collaboration between CalMatters and student journalists from across California. CalMatters higher education coverage is supported by a grant from the College Futures Foundation.

CLICK TO MANAGE