Sacred Groves, a 40-acre “green conservation” cemetery in Kneeland, pictured on a foggy morning. | Photo: G. Paoli.

###

For a place that prides itself on living close to the land, it’s strange that it has taken Humboldt County this long to develop a burial option that returns our loved ones to the Earth in an environmentally sustainable way, free from the chemicals and pollutants used in modern burials.

For many, modern burial practices — which have ironically come to be known as “traditional” — feel sterile and unnatural. Arcata resident Michael Furniss wants to change that through his nonprofit Sacred Groves, an eco-friendly “green conservation” cemetery nestled in the oak-studded hills of Kneeland.

“One of the things we want to make a contribution to is shifting American burial culture toward a more natural approach … that is as helpful to grieving families as it can be,” Furniss told the Outpost. “Cultural change is something we’re looking toward, not just this one facility. This is something that can be done, that people want and need, and it should become more available so that people have that choice, right?”

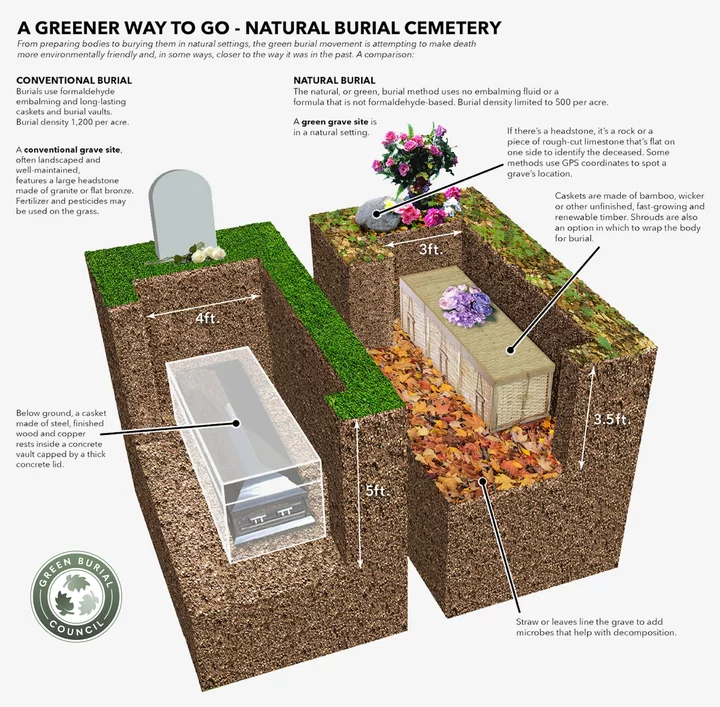

As you might guess, “green” burial is a natural approach to interment that forgoes chemical embalming, plastic liners, impermeable caskets and concrete vaults to encourage natural decomposition. In a green or natural burial, the body of the deceased is often wrapped in a cotton shroud or encased in a simple wicker casket. Everything that goes into the ground is biodegradable.

Modern burial versus green burial. | Graphic: Green Burial Council

Up until the mid-19th century, natural burials were standard practice in the United States, with most families opting to bury their loved ones in modest family plots or churchyards. Modern embalming practices came about during the Civil War era as a means to preserve the bodies of fallen soldiers long enough for their remains to be transported and returned to their families for proper burial. Embalmers learned they could make a decent profit preserving bodies, and eventually it became the de facto method in the U.S.

Green burials have grown in popularity in recent years as people look for new ways to reduce their carbon footprint, even in death.

Traditional burials use an estimated 4.3 million gallons of embalming fluid each year, along with 20 million board feet in hardwood for caskets and 1.6 million tons of reinforced concrete, according to an August 2025 report from U.S. Funerals Online. While cremations have a lesser environmental impact, the report notes that cremations are still responsible for nearly 700 million pounds of the nation’s annual CO₂ emissions.

“The standard practice of embalming people [uses] very toxic materials, and a lot of people aren’t interested in that,” Furniss said. “A lot of people like [the idea] of going back into nature and having your remains nourish an ecosystem. It sounds good to us. It’s very ‘Humboldt’ and we’re trying to provide that option here.”

‘I had this aspiration to create a tree-based cemetery’

Earlier this month, the Humboldt County Planning Commission approved a conditional use permit for Sacred Groves’ 40-acre cemetery, located on a sprawling ridgeline parcel owned by the Eric and Mary Almquist Trust. The cemetery will accommodate both single and family plots, allowing a maximum of 120 graves per acre, each with an accompanying tree. The cemetery will also accommodate people wishing to spread the ashes or compost of a loved one.

One day, this meadow will become a “restored savannah” with scattered, small oak groves. | Photo: Michael Furniss

The vision for Sacred Groves stems from an experience Furniss had while studying soil science and plant nutrition as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkley in the 1970s. Sitting outside of the university’s agricultural building on a drizzly afternoon, watching raindrops fall from the sky and disappear into the ground, Furniss found himself thinking about death.

“I thought, ‘When my time comes, I want to be in the root zone of a redwood!’ That sounds nice, you know?” he said. “I was always sort of on the side, looking for a cemetery where you could be planted under a tree, and I never really found anything. There are some minor exceptions, but basically, it wasn’t available. So, I had this aspiration to create a tree-based cemetery.”

Decades later, Furniss would coin the term “entreement,” which he describes as the “placement of individuals in the root zones of the trees, where their remains quickly ascend into the trees and other plants to nurture and nourish the environment above and around them.” Through “entreement,” Furniss aims to restore the oak woodland native to the region.

After working on a green burial site down in Sonoma County — which is still in the works — Furniss proposed a similar idea to Eric Almquist, founder and owner of the Almquist Lumber Company, and the pair got to work on a plan for a cemetery in Kneeland.

“I knew Eric was a real conservationist, and I knew he had some land, so I took him to coffee one day and asked [if he was interested],” Furniss said, noting that Almquist had used the land to grow hay in recent years. “As most ranch owners are, he’s always looking for sources of revenue that are not extractive [and] leave the land intact. He kind of brightened up and said, ‘Yeah, this sounds really interesting,’ and we just started working on it.”

Not wanting the cemetery to be a “money-making venture,” Furniss and Almquist agreed to form a nonprofit and assembled an 11-person board of directors to oversee operations, many of whom have backgrounds in conservation or end-of-life care.

[CLARIFICATION: Furniss contacted the Outpost following publication to note that the Sacred Groves nonprofit was formed “years ago” with a two-person board. Almquist is an independent landowner partnering with the nonprofit, but he is not a board member.]

Through the environmental review process required for the county-issued permit, Furniss was pleased to find that the Kneeland property has “particularly good soil” for decomposition.

“When we looked at the Kneeland site, it has everything,” he said. “There are places where you don’t want a cemetery, you know, with sandy soil that’s close to water. … When we went out there with an excavator and dug up some soil, I was super excited … [because] it’s a really suitable site. It’s on a ridge top, and there are no streams anywhere nearby. There’s no groundwater because there’s no recharge area until you get down the slope a ways.”

The Planning Commission agreed with Furniss’s environmental assessment of the site. The only issue raised by commissioners was about the proposed depth of the graves, which was set at 18 inches, the minimum depth required by state law.

Speaking at the Nov. 6 meeting, Commissioner Jerome Qiriazi asked if it was up to the county to “ensure that desecration doesn’t happen, or is that solely a liability for the property owner?” Staff said the matter was considered during environmental review, and the applicant had agreed to a utility easement as a condition of approval, which would prevent utilities from digging up potential gravesites in the future.

Staff also assured commissioners that animals digging up human remains buried at the recommended depth is virtually unheard of. Furniss agreed.

“When I first heard about the 18-inch depth minimum, I was like, ‘That’s not enough, animals will dig you up.’ … But it turns out animals don’t dig you up at that depth for a variety of reasons,” Furniss said. “One is that animals didn’t evolve with food being down there at that depth, and digging is really hard. Also, a decent topsoil is very good at capturing smells.”

“If there’s any animal interest or any digging at all at the site, we’ll respond to that right away,” he added.

Photo: Michael Furniss

The cemetery will begin facilitating burials in a few months, after a few legal and contractual matters are settled, Furniss said. As of this writing, more than 500 people have already contacted Sacred Groves to inquire about green burials and start planning their own plots subscribed to Sacred Groves’ emailing list.

Several people spoke in favor of green burials during the public comment section of the recent Planning Commission meeting, including Dr. Rebecca Stauffer, a former public health officer and board chair for Sacred Groves.

“The minute I learned about this possibility … I have been so enthusiastic about the thought of the cleanest, greenest, and really most beautiful way to bury our loved ones,” Stauffer said. “I have been the chief thorn in Michael’s side for years to keep this project going.”

Rick Littlefield, owner of Eureka Natural Foods, acknowledged the irony in green burials as a “new” approach to death rituals, given that natural burial has been around since humans started burying one another.

“It’s the oldest thing on the planet, and it’s ironic that it seems like it’s sort of a new age thing because the way we’re doing things now is the new thing,” Littlefield said. “This would be going back to the old thing.”

‘Think about your death every day’

Before closing out our interview, I asked Furniss if creating Sacred Groves and talking to new people about natural burials had altered their — or his own — perspective on death. He acknowledged that the death of a loved one is one of the most painful experiences a person can endure, but felt a more holistic approach to end-of-life services — “one that is connected with nature, love, community and beauty” — can help ease the grief.

“We’ve seen that in other tree-planting ceremonies I used to do without burial, where we planted a tree in memorial to a person, and it’s usually quite helpful to the family,” he said. “That last memory that you have with that person, that should be something that is positive and affirming. … And as the Buddhists say, ‘Think about your death every day.’ … Recognize that that’s going to happen, and it helps you to live more fully.”

CLICK TO MANAGE