Crabbers load pots onto their vessel in Trinidad Harbor on opening day of the season this past January. | File photo by Matt Filar.

###

Crab fishing in California has never been so complicated. Recent seasons have been delayed, truncated and subject to mandatory gear reductions for a variety of reasons, including a spike in whale entanglements, unhealthy levels of the neurotoxin domoic acid, low meat quality (a measurement of meat yield percentage) and ever-increasing layers of bureaucracy.

These complications were recently dubbed “the four horsemen of the crab apocalypse” by Dr. Craig Shuman, marine region manager for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). When he made the remark at a statewide fisheries forum led by Senate Leader Mike McGuire last week, he was likely half joking. After all, following a few years of lower prices the state’s crab fleet last year reached a record price for Dungeness of seven dollars per pound.

“We also had the highest number of active permits since the 2019-2020 season,” Shuman said during the forum.

Opening day was delayed in the northern zones of the state until January 15 due to meat quality issues and delayed in the rest of the state due to the presence of whales offshore. And when the fisheries did open it was under trap reductions in both zones. Still, by the time the season came to a close, California’s fleet had landed about eight and a half million pounds of crab worth close to $55 million, which is about average for the past 10 years.

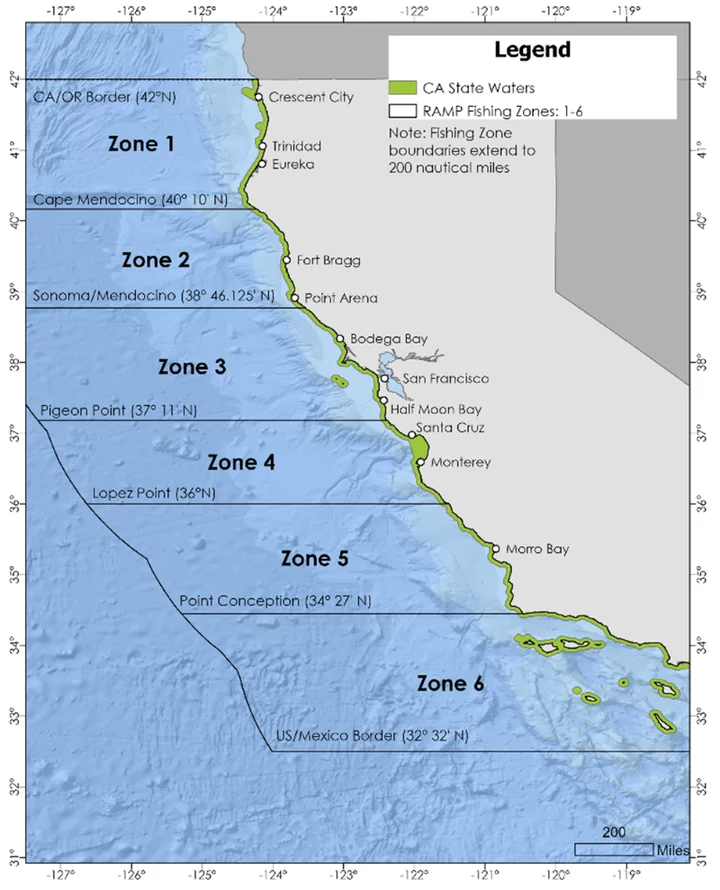

California’s Dungeness crab fishery is divided into six management zones. | CDFW.

###

Nonetheless, crabbers both locally and statewide have never felt so hemmed in by restrictions.

“It’s very hard to express and get out to the public the complexity of the hurdles and the regulatory constraints that we’re now bound by,” Harrison Ibach, president of the Humboldt Fisherman’s Marketing Association, told the Outpost in a phone interview last week.

Many of those regulations are contained in RAMP, CDFW’s Risk Assessment and Mitigation Program, which took effect five years ago. Designed to reduce the frequency of whale entanglements, the program was developed in the wake of a large, multi-year marine heatwave that would become known as “The Blob.”

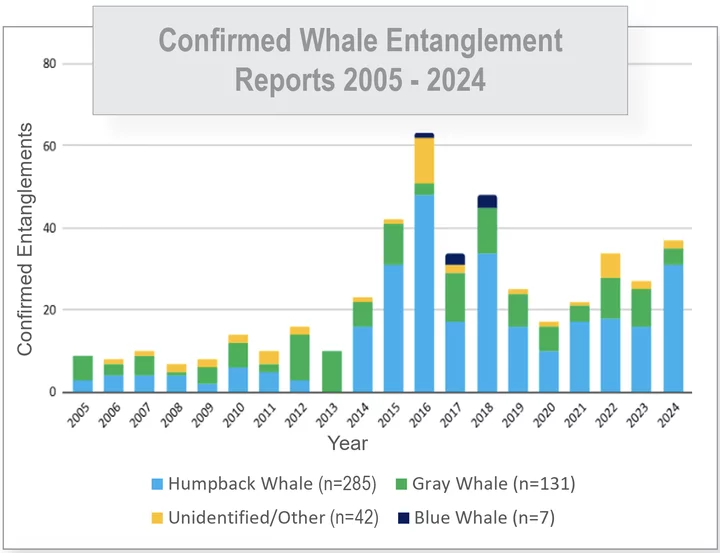

The phenomenon, which was likely tied to human-caused climate change, had serious impacts on the marine ecosystem, causing toxic algae to multiply while altering whale migration patterns, among other effects. In 2016 there was a record number of whale entanglements in fishing gear off the West Coast, and while the rate declined for a few years, the frequency remains elevated, as shown in the chart below.

Whale entanglements off the West Coast. | NOAA.

###

A new blob arrived this year as sea surface temperatures across the North Pacific hit a record high.

In partnership with California Ocean Protection Council and National Marine Fisheries Service, CDFW also established a Dungeness crab fishing gear working group, comprised of commercial and recreational fishermen, environmental organization representatives, and state and federal agencies.

The working group was formed in 2015. Two years later, the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity sued CDFW, arguing that the agency was moving too slowly to protect whales and thus in danger of violating the Endangered Species Act.

Ryan Bartling, senior environmental scientist supervisor at CDFW, said the development of RAMP complied with the terms of a settlement agreement for that lawsuit, though he said the agency had already been working toward such a program with the goal of reducing whale entanglements.

The program works, Bartling said, by giving the agency’s director “a suite of management options to choose from to try to draw down the number of entanglements that occur in any one year.”

Ibach sounded weary even talking about these regulatory mechanisms.

“For every entanglement that takes place in our fishery, it’s a point,” he said, “and now we’re graded on a point system. If we have too many points in a calendar year, we can’t go fishing.”

Even if whales don’t get caught up in crab gear, the season can be canceled or delayed based on whale sightings. CDFW conducts regular surveys while fishermen also report sightings.

Ibach voiced frustration at the array of regulations and restrictions that have resulted from whale entanglement while relatively less has been done to reduce vessel strikes, which are another source of whale mortality.

Lisa Damrosch, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen, likewise expressed annoyance at last week’s fisheries forum.

“The problem is we’re being held to an expectation of zero [entanglements],” she said. “That’s like saying you’re being held to an expectation of driving on the freeway and there’s never an accident — and if there is an accident, we’re going to stop driving. … And unfortunately for us, when there’s an accident, the commercial Dungeness crab fishery stops, but all the other ocean uses don’t. Ships don’t.”

A breaching humpback whale entangled with line through the mouth, around the right pectoral flipper and trailing along its body. The whale was documented off Laguna Beach. | Photo: Delaney Trowbridge Photography, via NOAA.

###

McGuire noted another factor negatively impacting the industry: namely, drastic cuts to fisheries funding to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) under the Trump administration. Partially driven by the Elon Musk-led Department Of Government Efficiency (DOGE), the cuts, which could total more than $1 billion, target specific programs including the Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund.

“If I could be so candid, we would be in real trouble if we did not see Proposition 4 funding in the state of California,” McGuire said at the forum, referring to the $10 billion climate bond measure approved by voters last year. Governor Gavin Newsom has appropriated roughly $267 million in Prop 4 revenues for coastal resilience and another $256 million to protect and enhance fish and wildlife resources.

But Wade Crowfoot, California’s Natural Resources secretary, said such spending is insufficient.

“As remarkable as the state investment has been … it’s not enough,” Crowfoot said during last week’s forum. “You know, the federal government simply can’t divest in our fisheries in order for our fisheries to recover — just can’t happen. … We haven’t seen [any] signs of support from this administration, really, in any respect.”

McGuire concurred, noting that state revenues intended to fuel expansion may instead have to be used to backfill the loss of federal dollars.

While fishermen may grumble about RAMP, Kate Kauer, fisheries strategy lead for The Nature Conservancy, defended the program as a science-based effort to reduce whale entanglement risk, though she noted that its success depends on accurate data about whale presence and abundance along the coast.

Speaking at last week’s forum, she said her organization advocated for putting $17 million in Prop 4 revenues toward vessel-based whale surveys, lost gear recovery efforts and investment in new types of gear. Newsom wound up allocating $11 million to CDFW for climate-ready fisheries.

The Promise of Pop-Up Gear

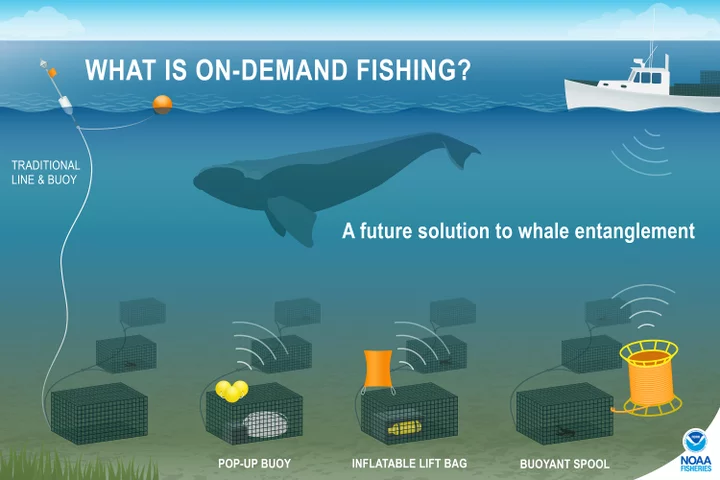

Environmental advocates and a growing group of fishermen believe that a relatively new type of crab fishing gear can serve as an important tool for reducing whale entanglement.

Geoff Shester, California campaign director for the nonprofit group Oceana, told the Outpost in a recent phone interview that whale-safe “pop-up” crab traps — also known as “ropeless” or “on-demand” gear — have already proven successful through experimental CDFW fishing permits up and down the coastline, though mostly in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Based on technology developed by the Department of Defense (recently renamed the Department of War) to hide mines, nuclear warheads and other expensive equipment on the ocean floor, pop-up crab traps are equipped with inflatable buoys that can be triggered to inflate remotely. Each of these traps can be lowered to the ocean floor and left there until a fisherman returns and sends an acoustic signal that triggers a release mechanism, inflating the flotation device and sending the crab pot back to the ocean surface.

“So there are no buoys at the surface or vertical lines anymore while the gear is fishing,” Shester said. “That that eliminates the risk of entangling the whales and sea turtles, which has been one of the major causes of fishery closures over the last last six or seven years.”

Graphic via NOAA.

###

These pop-up traps can also be tethered to a “ground line” with up to 50 traditional crab pots. Putting one pop-up on either end of such a line allows for all the pots to be retrieved at once.

“The goal is to restore the fishing opportunity that has been lost over the last few years, particularly in the springtime when the whales are returning — usually sometime around March or April,” Shester said.

This gear’s not cheap. One pop-up unit can cost $1,000-$1,500, according to Shester.

“It’s running about twenty to thirty thousand dollars [per vessel] to get the full setup out there,” he said. “What we’ve seen, though, is that that opportunity has has been well worth it.”

Most fishermen who tried this gear last season were able to make their initial investment back after just a couple of trips, Shester said.

“It does have some additional cost, but the the benefit in terms of the restored opportunity is more than compensating for that.”

When we talked to Ibach about pop-up gear, he was skeptical, referring to it as “a purple unicorn idea.” He said the technology is too expensive and unreliable to be implemented across the industry. He and other local fishermen worry that nonprofits will push to replace all traditional gear with pop-ups.

Bartling, the CDFW scientist, said that’s not the case.

“We think there’s always going to be a core season with traditional gear,” he told the Outpost.

Shester agreed, saying pop-up gear will simply offer crabbers a new tool.

“We’re hoping to eventually have multiple options out there so that fishermen can choose what works best for them and let the market decide what technology they want to use,” he said.

Under current state regulations, pop-up gear can only be approved after the traditional season has been closed. Any day now, though, the state is expected to release a new set of regulations under RAMP 2.0.

At last week’s fisheries forum, Shuman, CDFW’s marine region manager, said the new rules include updated thresholds for entanglement and whale sightings.

“For example, if we have three humpback whales entangled in one calendar year, that will automatically delay the start of that season the next year until January 1,” he said. There have already been three confirmed humpback entanglements in crab fishing gear this year, so if RAMP 2.0 had already been implemented, the season would automatically be delayed.

Shuman said he expects CDFW will likely take a conservative approach, meaning this year’s opening could easily be delayed again.

“I think the one silver lining of that, if we were under those rules, is [that] the fleet would have the certainty that they’ve been looking for,” Shuman said.

Ibach agreed. In recent years, the local fleet stood by week after week, waiting on new information to roll in regarding domoic acid and meat quality, unsure whether CDFW would open the season in a matter of days, weeks or months.

“And so we were constantly on the edge of our seat all fall and early winter, waiting to hear,” Ibach said. With this year’s high entanglement score, there should be more certainty.

“We would like CDFW to just state whether or not we’re delayed so everyone has a chance to better understand when we’re actually going to get started so we can plan life, execute other fisheries, make holiday plans, whatever.”

Shester, meanwhile, is optimistic about the future.

“It’s really exciting that through collaboration and getting these new technologies, fishermen are really leading the way towards innovation,” he said. “Without them, we wouldn’t have these new systems that are out there that have now moved past the testing phase [and] that are now ready for prime time.”

It may be a while yet before the local fleet agrees to adopt pop-up traps. Ibach said he doesn’t think they’ll work as well on our ocean floor given the amount of silt deposits we get from the Eel, Klamath and other waterways. Plus, local fishermen have always used traditional gear.

Even when told that neither CDFW nor nonprofits are pushing to have pop-up gear be the new standard, Ibach said the local fleet hopes to maintain the traditional fishery for the foreseeable future.

CLICK TO MANAGE