###

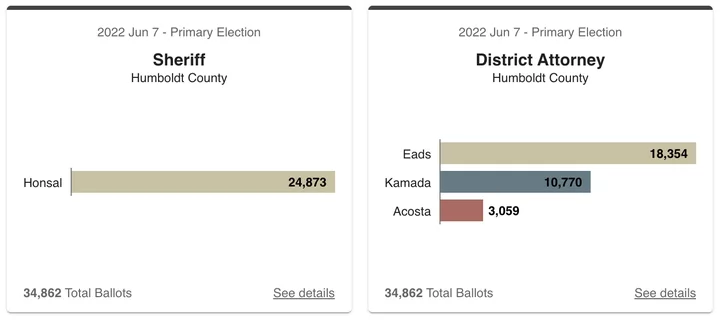

[NOTE: Humboldt County Sheriff William Honsal and Humboldt County District Attorney Stacey Eads were both elected (or re-elected, in the former case) in 2022. That, as you’ll read below, means that neither office-holder will have to face re-election until 2028. —RB]

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

A Bay Area sheriff facing imminent removal will get an extra two years in office if the move to oust her fails because of a little-noticed change in California law that moved the dates for local law enforcement elections.

San Mateo County Sheriff Christina Corpus has an unusual six-year term because state legislators in 2022 changed the law to put elections for sheriffs and district attorneys in the same years as presidential elections, which meant moving local campaigns originally slated for 2026 to 2028.

Every sheriff or district attorney who ran in 2022, including Corpus, got those two extra years, unless the official was removed from office in the meantime. That means they get two additional years for voters to forget about a scandal, or ride out other controversies.

San Mateo County moved a step closer to removing Corpus this week when retired Superior Court Judge James Emerson found cause to remove her on Monday night, more than a month after a two-week trial that included a cascade of allegations portraying a chaotic picture of her two-plus years in office.

Emerson found that Corpus had “a close personal relationship outside the boundaries of a professional working relationship” with a subordinate, unlawfully ordered the arrest of the president of the sheriff’s deputies’ union and retaliated against a captain who refused to conduct the union president’s arrest because he believed it violated state law.

“Appellant Sheriff Corpus’s purportedly non retaliatory justification for ordering an investigation against (the deputies’ union president) is, at the very least, questionable and, more likely, pretextual,” Emerson wrote in the advisory opinion.

Emerson’s recommendation will be heard in a separate hearing by the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors, which already voted 5-0 in June to proceed with the process to remove Corpus.

6-year-term once had an appeal

When former Corpus supporter Jim Lawrence first learned of the proposed change to election dates during Corpus’ 2022 campaign, he was delighted.

“We were so high on (Corpus), we campaigned for her, it was such a welcome change,” said Lawrence, board chair of the nonpartisan nonprofit Fixin’ San Mateo, which advocates for civilian oversight of the San Mateo Sheriff’s Office.

“We were gonna have someone pushing for visibility, transparency, accountability, and we didn’t have to deal with the (2026) election cycle. We could wait until 2028. There was just almost no downside.”

His feelings about the sheriff have changed.

“She had an amazing group behind her: house parties, street parties,” Lawrence said. “We got behind her and then she got in the office and made a complete about-face. It’s just, it’s really hard. How can the residents of San Mateo County live with this for another two-and-a-half years? It’s just unbelievable.”

Corpus could not be reached for comment.

The issue is of particular import to the group of San Mateo County residents who led a recall effort against Corpus this year.

After a county investigator found Corpus violated policies on nepotism and conflicting relationships, voters in April passed a measure empowering the county board of supervisors to remove her. If successful, it would be the first removal of a county sheriff in California history.

In the meantime, unions representing San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office deputies and sergeants have issued no-confidence votes in Corpus. Six cities in San Mateo County called for her ouster.

Why California moved sheriff elections

The law to change election years came about because California Democratic legislators sought to put elections for county offices on the years where voter turnout is highest, an effort that was opposed by Republicans in the Assembly and Senate.

“Overall, presidential elections attract significantly more voters than midterm elections,” the League of Women Voters of California wrote in 2022 in support of the bill. “Furthermore, midterm electorates include fewer people from underrepresented populations – including youth, Black, Latino, and Asian American people than do presidential electorates.”

The move faced opposition from the California State Sheriffs’ Association, which argued that presidential year elections are “no guarantee that voters will examine their choices more carefully.”

“A longer election ballot could result in voter fatigue and fewer votes cast in ‘down-ticket’ races,” the sheriffs’ association wrote in opposition to the bill.

Fresno County voters went as far as passing a ballot measure last year that would have forced the county to maintain off-year elections for sheriffs and district attorneys. Attorney General Rob Bonta sued, and a Fresno County Superior Court judge sided with Bonta and the state, keeping Fresno’s county elections on the presidential election calendar.

In Alameda County, the successful 2024 campaign to oust former District Attorney Pamela Price was lent heightened urgency by the prospect that she would serve until 2028 if not recalled. The Alameda County Board of Supervisors picked new District Attorney Ursula Jones Dickson as her replacement.

As for Corpus, even if the county board of supervisors votes to remove her, the Palo Alto Daily Post reports that a San Mateo Superior Court judge overseeing Corpus’ lawsuit against the county ruled that Corpus won’t be removed right away.

The judge ruled she should receive some extra time to challenge her removal: not an extra two years, but an extra two weeks.

CLICK TO MANAGE