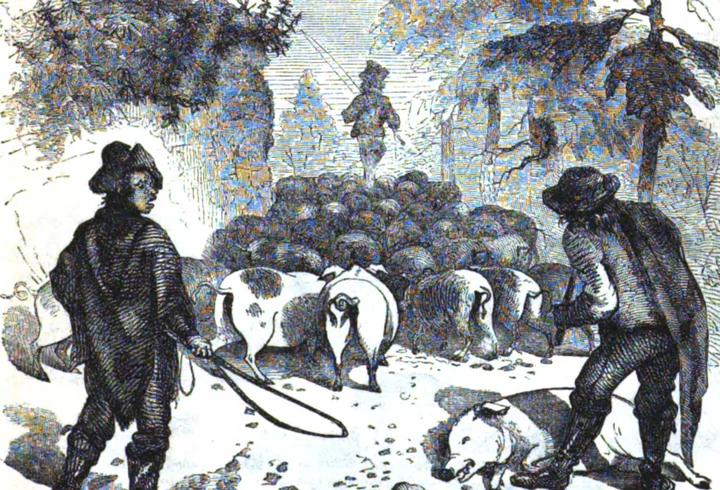

“Cuidadores de cerdos.” Revista mensual Harper’s New, octubre de 1857. Dominio público.

###

El año era 1905, el decimoquinto año de mi vida. Acababa de terminar la escuela de gramática en Blue Lake, Condado de Humboldt, California, y estaba buscando trabajo para poder ganar dinero y asistir al Colegio de Negocios Eureka. La matrícula en esa institución era de $120.00 a tiempo, o $85.00 en efectivo, para un curso de once meses. Muchos de ustedes, que eran de la vieja guardia, probablemente recordarán a C. J. Craddock, el Profesor Glenn, el profesor de matemáticas, y la Srta. Mae Smith, la instructora de taquigrafía y mecanografía.

Mi tío, Jack A. MacPherson, era dueño de una caballeriza en Blue Lake, con casi todo tipo de vehículos de tracción animal, surreys con franjas en la parte superior, buggies con llantas de goma, con y sin toldo, etapas de dos a seis asientos, una etapa de correo, el coche fúnebre de la ciudad, y 27 caballos. Empleaba a dos hombres en las caballerizas, uno de los cuales dormía en el establo por la noche para atender cualquier negocio o carruajes que regresaran durante la noche. Estos hombres eran Danny McCann y Vic Jensen.

Había muchos hombres viajeros en esos días, llamados “Drummers”, que necesitaban carruajes para transportarse a sí mismos y sus maletas de muestra de tienda en tienda, y a menudo pedían un conductor, ya que no tenían tiempo para cuidar del caballo. Si era un viaje que requería pasar la noche, mi tío debía encontrar un conductor para la ocasión, y me llamó varias veces para este tipo de trabajo.

El Sr. Ike Denney, conductor de la etapa de correo, solía salir de Blue Lake hacia la Reserva India Hoopa, a 50 millas en las montañas, a las 6 de la mañana de los lunes, conducir hasta la mitad, a la estación de correo, pasar la noche, y recorrer la distancia restante el martes, quedarse hasta el miércoles para preparar el correo y la carga, descansar a los animales para su viaje de regreso, luego partir de Hoopa a las 6:00 de la mañana del jueves, de vuelta a la estación de correo, pasar la noche allí y llegar a Blue Lake el viernes por la noche.

Platt Lupton tenía una pequeña finca a unas 14 millas por este camino hacia Hoopa, y a 2-3 millas a la izquierda, alejado del camino principal. En ese viernes en particular, Platt caminó hasta el camino principal a tiempo para tomar la etapa de correo en su viaje de regreso a Blue Lake. Cuando llegaron a la caballeriza, Platt le dijo a mi tío que había venido a la ciudad para comprar un buen bucboard de segunda mano para usar alrededor de su rancho. “Mac” pensó que tenía justamente la carreta, y acordaron reunirse temprano el sábado por la mañana. Luego Platt se fue al Hotel Blue Lake para pasar la noche.

Regresó a la caballeriza temprano el sábado por la mañana, y se hizo el trato, con el entendimiento de que se proporcionaría un caballo y un conductor para transportar la carreta a la finca de Platt. Quería empezar el viaje a casa para las 2 p.m., del sábado, ya que tenía que hacer algunas tareas el domingo. Luego bajó al salón a tomar una copa o dos antes de dejar la ciudad. “Mac” me llamó a la 1:30 p.m. preguntando si podía conducir por él, y a las 1:45 p.m. ya estaba en la caballeriza, y comenzamos a prepararnos para el viaje.

Enganchamos al caballo a la carreta, pusimos una silla de montar, mantas, cabezada, un costal y 4 pies de cuerda para empacar las correas para el regreso. A las 2 en punto, Platt no había llegado. Los hombres de la caballeriza fueron a ver qué estaba causando la demora. Platt estaba bastante ebrio y no parecía tener prisa por comenzar el viaje de regreso. Los hombres regresaron, desenganchamos al caballo y lo pusimos de regreso en el establo. A las 3 en punto los hombres bajaron una vez más. Platt, para entonces, no le importaba si volvía a casa.

“Mac” dijo que esperaríamos hasta las 4 p.m. y si no había llegado para entonces, irían a buscarlo aunque tuvieran que llevarlo.

At 4 o’clock we started to get ready again. “Mac” said: “Now that you are getting such a late start, I am going to give you ‘Silver-mane Fanny’ to drive. She is awfully good in the dark and will automatically yield one-half the road if you should meet anyone.” The men headed for the saloon and practically carried Platt back to the stable. He was placed in the buckboard, feet forward, under the seat, with his bead on the seat of the saddle, padded with blankets to make him comfortable as possible.

Now we were off for his ranch. The hour was 4:30 p.m. Some four miles later we passed the John Anderson sheep ranch, just at the base of the mountain. Here they raised hundreds of head of sheep each year. From this point on I was not too familiar with the road. About 3 and a half miles beyond was a stand of timber, which hadn’t been logged yet, and through which we would have to pass.

As it was a bright, moonlit night. I did not think this would pose any problem, but when we entered the forest it was so dark that I could not see my hands before me. I could hear Fanny’s footsteps on the gravel road, and it was getting pretty lonely. I called down to Platt a couple of times, with no response. He was still dead drunk.

Through the quietness of the timber, it seemed I heard a man’s voice, and as we advanced, step by step, the voice became louder. I saw the light of a lantern and a man on horseback. I could see by his light that I was approximately 4 feet from the bank on the right and about 8 feet to the shoulder of the road on my left. I stopped the wagon, and Mr. Swanson, a hog raiser from Hoopa, rode up beside me.

He said that he had 500 head of razorback hogs for the Bull slaughterhouse in Arcata, and that he had come from the mail station that morning, expecting to reach the Anderson ranch before dark, but that it bad been such a hot day and the hogs were tired, so he bad to travel very slowly. He still had about four miles to go before reaching the Anderson ranch.

He started off down the road, calling to the hogs, and for the next 10 or 15 minutes it was perfect bedlam. There were hogs under the buckboard, and on both sides. I could feel the rig sliding back and forth across the road, and was afraid the wheels would cave in and let us down in the path of the animals. I slid off the seat and down onto my knees, astraddle Platt’s legs, to make us less top-heavy.

At the rear of the drove of pigs were two burly young Indians, each with a straight limb, about 4 feet long, which they used as a sort of cane to urge the slower hogs along. I suppose they had noticed that the drove had been delayed somewhat, and it made them angry, for when they reached us, they cursed us and one of them struck Fanny across the nose with his stick, knocking her down onto her stomach. They went on, leaving us helpless there in the road.

I waited for a time in the seat, thinking my horse might get to her feet. I could hear her struggling to rise, but the wagon shaft made it the more difficult for her. Climbing down the left side of the rig, I went to her head and patted her neck and stroked the swollen nose.

We were on a rather steep grade and I didn’t have anything to block the wheels, had I been able to find a rock or limb in the darkness, and I did not dare free Fanny from the shaft. I took hold of the lines at her head and kept talking soothingly, patting and rubbing her sore nose, and on the third attempt, she managed to struggle to her feet.

We waited a while for her to regain strength, then started on. We were two-thirds through the timber by now. “Mac” had told me that when we emerged from the timber stand, in the moonlight I would see a very large rock to the right, silhouetted against the sky, and that I was to go no further than a quarter mile beyond this rock, where I would see Platt’s mailbox and his private road.

We found the landmarks, and still had two miles to go down Platt’s road, which was much overgrown, and two or three times the overhead branches almost raked me off the wagon seat. We reached our destination in about three-quarters of an hour. I approached his cabin and found the door unlocked, went in and lit the lamp, and then had before me the task of getting him out of the rig and on his feet again. Half-dragging him into the cabin, I dumped him upon the bed, clothes, shoes and all, put out the lamp, closed his door and proceeded to ready myself for the return trip.

I unharnessed Fanny, loaded the harness into the gunny sack, tied it with bailing rope and placed it on the seat of the buckboard. Then, blanketed, saddled and bridled Fanny, mounted the saddle and eased her up to the buckboard from which I pulled the sack of harness over in front of me on the horn of my saddle. Feeling much relieved that this task was accomplished, I started homeward.

It was much easier traveling on horseback than with the rig. I had passed through the timber stand and out into the moonlight again, when suddenly, a panther cried within about 12 feet of the road. Fanny almost jumped from under me. In my efforts to hold my position on her back, the sack of harness fell to the ground and Fanny dashed down the road as fast as she could travel.

I allowed her to run for about a quarter of a mile, then reined her in and tried to quiet her as best I could. I hesitated for some time, thinking maybe to leave the sack of harness in the road and return for it in the morning. Then, since it was a brand new harness, costing $25, a lot of money in those days, and just might jeopardize my chances of getting more driving to do should I abandon it, decided to go back for it.

Fanny was not too cooperative. She snorted and pranced about in circles. After considerable coaxing and persuasion, I managed to get her started back up the road. I knew there would be no trouble in finding the big sack, she would let me know when we approached it. Sure enough, she walked within 60 feet of the “bulk” and would go no closer.

By moonlight I could see the object in the middle of the road, but could not distinguish whether it was the sack of harness or the panther crouched there. I watched it for several minutes, while my horse pranced and wheeled around in the road, and, seeing no movement, started my approach.

I dismounted, taking the reins down over Fanny’s head, putting my right arm through them to the elbow, so that if the panther should cry out again, my horse would not get away from me. We started toward the bulky object very slowly. The closer we came, the more convinced I was that it was the sack of harness. I walked up to it and retrieved it with both ends of the baling rope, leaving a loop in the middle, by which to lift it over the saddle horn, remounted, and pulled the sack up before me. Once more we started for home.

As we passed the Anderson ranch I could see the hogs in his corral. From then on I really enjoyed the ride in the moonlight, arriving at the stable approximately 2 a.m. Sunday.

When the night man learned of my trials and saw poor Fanny’s swollen nose, he was pretty much disturbed and said we would demand an apology from the Indians when they came through town; but they did not come. Mr. Swanson took the Scottsville road, skirting the town. I suppose he thought they would have less trouble going that way, as there were no intersections and most of the homes had front-yard fences.

We did not see the Indians on their way to Arcata nor on the return to Hoopa, and we never did get an apology from them.

###

The piece above was printed in the May-June 1970 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE