(VIDEO) There’s More Humboldt in This Full-Length Trailer for DiCaprio’s ‘One Battle After Another’

Ryan Burns / Thursday, March 27, 2025 @ 10:02 a.m. / MOVIED!

###

We open on the back of a man walking away from camera and through the swinging double doors of a grocery store’s back room.

Cut to: Handheld shot, on the move. The man is Leonardo DiCaprio, squinting in the sunlight, grabbing a pair of sunglasses off a rotating rack in the produce aisle. We recognize the lettering on the store’s back wall, and in the next shot we see the familiar window paintings and that telltale “Deli” mural. This is Murphy’s Market, Cutten location.

There’s more Humboldt to be spotted over the rest of this full-length trailer for “One Battle After Another,” the latest feature film from renowned director Paul Thomas Anderson (“Boogie Nights,” “There Will Be Blood,” “Phantom Thread”).

We spotted the Arcata pedestrian bridge, with Raliberto’s Taco Shop in the background, for example. And an extended sequence of Leo on the phone outside Murphy’s. No shots of Eureka High this time around, though. Regardless: Color us very excited for this movie’s release, scheduled for Sept. 26.

Costars include Benecio Del Toro, Sean Penn, Teyana Taylor, Regina Hall, Wood Harris, Alana Haim and newcomer Chase Infiniti.

Relive last year’s local production activity via the links below.

###

PREVIOUSLY

- Film Set to Shoot in Eureka is From Renowned Director Paul Thomas Anderson, With Leonardo DiCaprio, Sean Penn and Regina Hall, According to Industry Reports

- (PHOTOS) Hollywood Magic Transforms Cutten Plaza Into a Mexican Mini-Mall for DiCaprio Movie Production

- Northtown Arcata Will Be Swarming With Movie Folk Tomorrow, As Bigtime Production ‘BC Project’ Films in the Neighborhood

- (WATCH) First Look at Leonardo DiCaprio In Character for New Paul Thomas Anderson Film Currently Filming in Humboldt

- MOVIE DAY! My Diary of Hanging Around Waiting For The Stars to Show Up In Northtown, and the Things I Saw There

- Buh-Bye, Leo! Local Production on Paul Thomas Anderson’s New DiCaprio Movie Has Wrapped

- Alas, We Have to Wait Until Summer 2025 to See Leo Dicaprio’s Locally Filmed Paul Thomas Anderson Movie

- (VIDEO) Teaser Trailer Just Dropped for the New DiCaprio Movie Partly Filmed in Humboldt and Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 17 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Feb. 6

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

100% Humboldt, with Scott Hammond: #107. Jan Friedrichsen: Veteran Rescuer Explains How Search Dogs Track, Find, And Bring People Home

RHBB: Crash Blocks Lane on Northbound U.S. 101 at Humboldt Hill Onramp

RHBB: Crash off 101 into Trees North of Willits

Study Finds: When Moths Freeze: How LED Streetlights Are Silencing the Night

Marijuana Enforcement Team Busts Illegal Indoor Grow on Freshwater Road, Sheriff’s Office Says

LoCO Staff / Thursday, March 27, 2025 @ 9:41 a.m. / Cannabis , Crime

Photos: Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office

###

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

On March 26 around 8 a.m., deputies with the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office Marijuana Enforcement Team (MET) served a search warrant to investigate indoor illegal cannabis cultivation near the 1800 block of Freshwater Rd. in Eureka.

The parcel investigated during the service of the warrant did not possess the required county permit or state license to cultivate cannabis commercially. During the investigation, John McGhan, 42, of Eureka, was identified as the owner of the parcel.

During the service of the warrant, deputies eradicated approximately 168 cannabis plants growing in a converted residential garage. Deputies seized and destroyed over 37lbs of cannabis bud and over 37.5lbs of cannabis shake.

McGhan was placed under arrest and transported to the Humboldt County Correctional Facility to be booked for the following charges:

- Illegal Cultivation of Marijuana—H&S 11358

- Possession of Marijuana for Sale—H&S 11359

- Maintaining a Drug House—H&S 11366.5

Anyone with information about this case or related criminal activity is encouraged to call the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office at (707) 445-7251 or the Sheriff’s Office Crime Tip line at (707) 268-2539.

Inside the Efforts to Identify Humboldt County’s Missing Dead

Dezmond Remington / Thursday, March 27, 2025 @ 8:09 a.m. / Crime

Image by Carley & Matt T. via Pexels.

In 1998, someone riding a horse on Clam Beach found a chunk of bone and called the police.

The sheriff’s office did what they could; an anthropologist determined it was human, that it was the top of a skull, and that it came from a man. The Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office sent a DNA sample to the Combined DNA Index System, a DNA database maintained by the FBI. It wasn’t a match with any DNA from any missing people in that database, and there the trail ended.

But 30 years on, DNA technology has improved to the point where there’s a chance that person could be identified.

The Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office has been working with Othram, a company that helps solve cold cases with DNA matching. Though this particular case is still currently in the works, Othram has helped HCSO solve six previous cases over the last two years, including identifying a victim of serial killer Wayne Adam Ford.

One victim was in her mid-twenties when she was killed by Ford, dismembered and thrown into Ryan Slough in 1997. Her torso was found by a duck hunter in October of that year, and no one knew who she was until 2023. According to HCSO cold case investigator Mike Fridley, even Ford tried helping police identify her after he turned himself in in 1998.

But she had a cousin who had sent their DNA to 23andMe, a direct-to-consumer DNA testing company that analyzes DNA samples for genetic markers and estimates a customer’s ancestry, and Othram managed to find that link.

Fridley reached out to the cousin and asked if he had any missing relatives. He said he had: One of his cousins, Kerry Ann Cummings, had been missing since the ‘90s, when police found the remains. Fridley found her sister, sent her DNA to the Department of Justice, and waited.

“They never tell you that this is a direct relative,” Fridley said. “They give you odds. This one was something like a 360 million to one chance that it wasn’t a direct relative, which is basically 100 percent.”

Fridley has been one of HCSO’s cold case investigators for about four years. He worked for HCSO before this chapter of his life began for 30 years, retiring as a lieutenant. Retirement got a little stale, Fridley thought working on cold cases would be interesting, and he decided he’d come back. It’s a frustrating job with its own set of benefits. Identifying missing people can be “kind of a high,” Fridley said.

The Clam Beach remains aren’t nearly as simple a nut to crack. What Othram has managed to figure out is that the closest direct ancestor they can find to whoever that person was is a woman named Catherine Francis Prince, a member of the Bear River Tribe. Although Fridley would love to simply just ask her about any missing relatives she has, she was born in 1843, and although she lived a pretty long life, it wasn’t quite long enough to answer that question.

The process of finding these closest direct relatives is a long one. Researchers start with the DNA they’ve managed to extract from the dead, then compare it with their DNA databases, vast troves of data composed of DNA samples from millions of people. Some of that data is from companies like 23andMe, some of it from government indices. Hopefully, they find a relative. Sometimes it’s a close one, sometimes it’s a third or a fourth cousin a few steps removed.

Investigators then move to looking at public records to find missing relatives of that match, and then try to get a DNA sample from the closest living family member of that person. If someone has long been deceased, there might be a grandchild or a niece around to test. Fridley is looking for anyone related to Prince to hopefully find a closer relative that might know of any missing relatives.

There are no certainties in this game, no easy solutions. There’s a possibility that the remains from Clam Beach are from an burial site, or even washed up here from far away. According to Fridley, there are even times when people who jumped off of the Golden Gate Bridge will wind up on Humboldt’s beaches, grisly gifts from the ocean’s currents and temperamental storm swells.

Fridley said there had been a large amount of public interest in the Clam Beach case. Amateur genealogists have reached out to him offering help reconstructing family trees, and Prince’s relatives have offered their genetic codes.

It wasn’t too difficult to find some of them. Fridley said that the person working for the Bear River Band he called to ask about Prince’s ancestry turned out to be her great-great-nephew. But no one on one side of the family can figure out anyone that’s missing. That means investigators have to go up a couple rungs on the genetic ladder to Prince’s grandparents, people born in the 18th century whose existence may never have generated any records, so they can figure out who the other side of the family is and ask them if anyone ever went missing. It’s a two-step dance that always ends in a backpedal.

Even if the identity of the dead man from Clam Beach is ever discovered, Fridley probably won’t get to take it off of Humboldt County’s missing persons list if he’s on there. An intimidating document with over 150 people listed, it doesn’t do much to allay Humboldt’s reputation as a place where people wind up and then vanish.

There are some factors that make that list so long. Humboldt has many millions of acres of forest and ocean and rivers, places where it’s easy to die and never reappear. Many were casualties of cannabis-related violence in the ‘80s. Some people move here, stop calling their family, and then get added to the list when their family files a missing persons report. But even when people do find identifiable human remains, they often stay on the list. If only a chunk of them is found, and their DNA is removed from the databases, then any of their body parts found in the future won’t turn up as a match.

“When I first started doing this, I had a case where they recovered the guy’s head,” Fridley said. “I’m, like, ‘Well, we could take him out of the system. He can’t live without a head. He’s dead.’ And the sergeant said [we] gotta leave him in there…There are cases that are never going to go away. They’re going to be there long after you and I are gone.”

Othram charges a hefty fee for their services (Fridley said they had looked at HCSO’s six cases for between $8,000 and $11,500 apiece), but he thinks it’s a worthy price to pay. When he managed to contact Kerry Ann Cumming’s sister, she was devastated at first.

“At the beginning, she was crying and sad, and then she was happy to find out what happened to her sister,” Fridley said. “If you had your mom go missing, you never hear from her, you’d always wonder what happened to her…When I called her she said, ‘I know exactly why you’re calling. That was my sister.’”

“It was bittersweet,” Fridley continued. “You’re thinking, ‘Maybe she’s living and she’s OK and she’s doing her own thing,’ and then you find out, ‘No, she’s dead.’ But then again, [at least] I know where she’s buried.”

Will This Bill Be the End of California’s Housing vs Environment Wars?

Ben Christopher / Thursday, March 27, 2025 @ 7:43 a.m. / Sacramento

New housing construction in a neighborhood in Elk Grove on July 8, 2022. Photo by Rahul Lal, CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

For years California has been stuck in a recurring fight between legislators who want the state to turbocharge new home construction and legislators determined to defend a landmark environmental protection law.

The final showdown in that long-standing battle may have just arrived.

A new bill by Oakland Democratic Assemblymember Buffy Wicks would exempt most urban housing developments from the 55-year-old California Environmental Quality Act.

If it passes — a big if, even in today’s ascendent pro-building political environment — it would mean no more environmental lawsuits over proposed apartment buildings, no more legislative debates over which projects should be favored with exemptions and no more use of the law by environmental justice advocates, construction unions and anti-development homeowners to wrest concessions from developers or delay them indefinitely.

In short, it would spell the end of California’s Housing-CEQA Wars.

“If we’re able to get it to the governor’s desk, I think it’s probably one of the most significant changes to CEQA we will have seen since the law’s inception,” said Wicks.

Wicks’ broadside at CEQA (pronounced “see-kwah”) is one of 22 housing bills that she and a bipartisan group of legislators are parading out Thursday as a unified “Fast Track Housing Package.” Wicks teed up the legislative blitz earlier this month when she released a report, based on the findings of the select committee she chaired last year, that identified slow, uncertain and costly regulatory approval processes as among the main culprits behind California’s housing crisis.

The nearly two dozen bills are a deregulatory barrage meant to blast away at every possible choke point in the housing approval pipeline.

Most are eye-glazingly deep in the weeds.

There are bills to standardize municipal forms and speed up big city application processes. One bill would assign state and regional regulatory agencies strict timelines to approve or reject projects and another would let developers hire outside reviewers if cities blow the deadlines. Different bills take aim at different institutions identified as obstructionist: the California Coastal Commission, investor-owned utilities and local governments throwing up roadblocks to the construction of duplexes.

Wicks’ bill stands out. It’s simple: No more environmental lawsuits for “infill” housing. It’s also likely to draw the most controversy.

“It’s trying something that legislators have not been willing to try in the past,” said Chris Elmendorf, a UC Davis law professor and frequent critic of CEQA. “And the reason they have not been willing to try in the past is because there are a constellation of interest groups that benefit from the status quo. The question now is whether those interest groups will kill this or there’s a change in the zeitgeist.”

A spokesperson for CEQA Works, a coalition of dozens of environmental, conservation, and preservation advocacy organizations, said the members of the group needed more time to review the new legislation before being interviewed for this story.

A spokesperson for the State Building and Construction Trades Council, which advocates on behalf of tens of thousands of unionized construction workers in California, said the organization was still “digging into” the details of the bill.

What’s the big deal?

The California Environmental Quality Act has been on the books since 1971, but its power as a potential check on development has ebbed and flowed with various court rulings and state legislative sessions. The act doesn’t ban or restrict anything outright. It requires government agencies to study the environmental impact of any decisions they make — including the approval of new housing — and to make those studies public.

In practice, these studies can take years to complete and can be challenged in court, sometimes repeatedly.

Defenders of how the law applies to new housing argue that CEQA lawsuits are, in fact, relatively rare. Critics counter that the mere threat of litigation is often enough to pare down or entirely dissuade potential development.

As state lawmakers have come around to the idea that the state’s shortage of homes is the main driver of California’s punishingly high cost of living — and a major political vulnerability for Democrats — CEQA has been a frequent target.

Until now, attacks on the law have generally come in the form of selective carve-outs, conditioned exemptions and narrow loopholes.

“If we’re able to get it to the governor’s desk, I think it’s probably one of the most significant changes to CEQA we will have seen since the law’s inception.”

— Buffy Wicks, Assemblymember, Democrat, Oakland

There’s the law that lets apartment developers ignore the act — but only so long as they set aside some of the units at a discount and pay their workers union-level wages.

A spate of bills from two years ago waived the act for most homes, but only if they are reserved exclusively for low-income tenants.

There was the time a CEQA lawsuit held up a UC Berkeley student housing project over its presumptively noisy future tenants and the Legislature clapped back with a hyper-specific exemption.

Wicks’ new bill is different, in that the exemption is broad and comes with no strings attached. It would apply to any “infill” housing project, a general term for homes in already built-up urban areas, as opposed to fresh subdivisions on the suburban fringes.

That echoes a suggestion from the Little Hoover Commission, an independent state oversight agency, which made a series of “targeted reform” proposals to the environmental law last year.

“California will never achieve its housing goals as long as CEQA has the potential to turn housing development into something akin to urban warfare — contested block by block, building by building,” the report said. “The Commission recommends that the state exempt all infill housing from CEQA review — without additional conditions or qualifications.”

Wicks bill defines “infill” broadly as any housing in an urban area that’s either been previously developed or surrounded by developed lots and doesn’t sit on a wetland, a farm field, a hazardous waste site or a conservation area.

The site also has to be less than 20 acres to qualify for the exemption, but at roughly the size of 15 football fields, that’s not likely to be a limiting factor for most housing projects.

One possible rub: When a housing project varies from what is allowed under local zoning rules and requires special approval — a common requirement even for small housing projects — the exemption would not apply.

Enter another bill in the housing package, Senate Bill 607. Authored by San Francisco Democratic Sen. Scott Wiener, that bill would also exempt those rezonings from CEQA if the project is consistent with the city’s state-mandated housing plan.

“Put the two bills together and it’s really a dramatic raising of the ante in terms of what the pro-housing legislators are willing to put on the table and ask their colleagues to vote for,” said Elmendorf.

An environmental case against the Environmental Quality Act?

Environmental justice advocates regularly use the law to block or extract changes from developments that they argue will negatively affect low-income communities. Developers and lawyers regularly claim that organized labor groups defend the law to preserve it as a hard-nosed labor negotiation tool. Well-to-do homeowners who oppose local development projects for any reason may turn to CEQA to stall a project that otherwise passes muster on paper.

All these groups have pull in the California capitol. That may be one reason why this kind of bill hasn’t been introduced in recent memory.

Wicks said she thinks California’s Legislature may be ready to take up the cause. The severity of the housing crisis, Democratic electoral losses over the issue of unaffordability, and the urgency to rebuild in the wake of the Los Angeles wildfires all have created a “moment” for this argument, she said.

She, and other supporters of the bill, also insist that the cause of the environment is on their side too.

“I don’t view building infill housing for our working class communities in need as on par with drilling more oil wells in our communities, yet CEQA is applied in the same way,” she said.

Researchers have found that packing more homes into already-dense urban areas is a good way to cut down carbon emissions. That’s because living closer to shops, schools, jobs and restaurants mean more walking and biking and less driving, and also because downtown apartments, which tend to be smaller, require less energy to heat and cool.

Even if infill is, in general, more ecologically friendly than sprawl development, that doesn’t mean that a particular project can’t produce a wide array of environmental harms. In a letter to the Little Hoover Commission, the California Environmental Justice Alliance, a nonprofit member of CEQA Works, highlighted the 2007 Miraflores Senior Housing project in Richmond.

A final environmental impact report for the project “added strategies to mitigate the poor air quality, water quality, and noise impacts” associated with the development and “included plans to preserve the historic character of buildings, added key sustainability strategies, and improved the process for site clean up.” That report was certified by the city in 2009.

Jennifer Hernandez, a land-use attorney and one of the state’s most prolific critics of CEQA, said local permit requirements and public nuisance rules should be up to the task of addressing those problems, not outside litigation required.

“The whole construct of using CEQA to allow the dissenting ‘no’ vote, a community member with resources, to hold up a project for five years is just ridiculous,” she said. “It’s like making the mere act of inhabiting a city for the people who live there a harm to the existing environment.”

California Food Banks Brace for Funding Cuts, and Not Only From the Trump Administration

Jeanne Kuang / Thursday, March 27, 2025 @ 7:36 a.m. / Sacramento

The distribution line at the Sacramento Food Bank and Family Services in the Arden-Arcade area of Sacramento on March 25, 2025. Photo by Louis Bryant III for CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

Five years since the COVID-19 pandemic upended the economy and made millions experience hunger for the first time, demand at the Sacramento Food Bank and Family Services is still higher than ever.

The number of monthly clients has risen to 310,000, more than double the number of people the food bank served before the pandemic, spokesperson Kevin Buffalino said.

So it was a blow this month, he said, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture halted hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funds for food banks. Caught up in the freeze were 11 truckloads of food – 400,000 pounds – that the Sacramento food bank was expecting over the next few months.

A total of 330 truckloads bound for food banks across the state has been suspended, according to the California Association of Food Banks, with no indication of when or if they’ll be delivered. The biggest potential hit is to the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank, where 90 expected truckloads are in limbo.

The orders were promised during the Biden administration, which in December announced a bonus round of food orders on top of deliveries the USDA normally makes to food banks.

The freeze of the bonus orders came as food banks brace for other cuts — both from a new Trump administration intent on reducing federal spending and from California’s own state budget deficit after several flush budget years in the pandemic. In Washington, Congress is also considering cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, which sends about $1 billion a month to low-income Californians to buy groceries.

A volunteer asks a woman her canned food preference at the Sacramento Food Bank and Family Services in the Arden-Arcade area of Sacramento on March 25, 2025. Photo by Louis Bryant III for CalMatters

But food programs are just one of many competing priorities the Democratic-dominated state Legislature will have to balance as California starts to get a picture of how federal cuts may affect the state and its $322 billion budget. California receives more than $314 billion in federal funds for food benefits, health coverage and other social services each year, while federal grants to nonprofits and private contracts total more than $81 billion.

Department of Finance spokesperson H.D. Palmer said it’s still too early to determine whether California can afford to make up the federal spending being cut.

Already, the food banks association is urging lawmakers not to reduce the state food assistance dollars, but they’ll be jockeying for attention amid a myriad of real and potential federal cuts in everything from higher education to rural road repairs, refugee resettlement services and the massive low-income health program Medicaid.

“These are Sophie’s choices,” said Assemblymember Gregg Hart, a Santa Barbara Democrat who chairs a budget subcommittee that’s evaluating potential federal funding shortfalls. “Every single thing that we could talk about has a federal funding connection that’s in jeopardy and the state just doesn’t have the money to backfill it.”

The demand for food has not slowed

When a persistent foot condition forced Antoinette Turner to retire early last fall from her longtime job on a hospital graveyard shift, she looked for ways to save.

The 61-year-old was “rationing” her savings and accepting help from her son. For the first time in her life, she started going to the Sacramento food bank.

On Tuesday morning in a Sacramento church parking lot, she made her way down an assembly line of grocery pallets as volunteers offered canned soup, peanut butter, beans, rice and frozen turkey breasts. Hundreds of people were expected, including retirees, disabled veterans and immigrant families from Russia, Ukraine and Afghanistan who settled in the diverse Sacramento suburbs.

“It’d be sad,” if the organization had to cut back, Turner said. “It makes my life easier.”

First: Antoinette Turner, 61, a retiree and regular food bank visitor, at the Sacramento Food Bank and Family Services. Last: Turner receives canned soup from a food bank volunteer in the Arden-Arcade area of Sacramento on March 25, 2025. Photo by Louis Bryant III for CalMatters

A confluence of cuts could force the food bank to do just that, Buffalino said.

Earlier in March, the USDA terminated a Biden-era grant program that gave food banks and tribal governments money to purchase food from local farmers.

California food banks have gotten more than $80 million through the program since 2022, with some grants expected to last through mid-2026. They were expecting another $47 million in the program’s next round, before that was cut on March 7, said state Department of Social Services spokesperson Jason Montiel.

It was unclear why the grant was canceled and the orders halted. USDA officials did not respond to queries sent to the agency’s press email seeking comment. Under Trump, federal agencies have moved to halt or cut grants in a quest to purge waste and spending on programs that don’t meet the administration’s ideological tests.

California, too, is slated to reduce food banks’ funding. For several years when the state had a record surplus, it devoted millions of additional dollars to a state program called CalFood that allows food banks to purchase from local farmers or food producers such as tortillerias.

Those boosts gave food banks about $60 million a year through CalFood over the past three years; in the budget Gov. Gavin Newsom has proposed for the fiscal year that starts in July, that funding would revert to $8 million.

California food banks depend on aid

The federal and state food-purchasing funds have made up the majority of the $3.5 million the Sacramento food bank spends to buy food annually, Buffalino said.

Purchased food makes up 40% of the groceries the food bank gives away; the rest is delivered by the USDA or recovered from supermarkets that can no longer sell it.

A pallet of canned goods and peanut butter, among many of the goods that will be distributed to around 700 families at the Sacramento Food Bank and Family Services in the Arden-Arcade area of Sacramento on March 25, 2025. Photo by Louis Bryant III for CalMatters

With sharp reductions in both purchasing funds, Buffalino said the Sacramento food bank will either have to rely more heavily on private donations or cut back on how much it gives each recipient.

Though demand at the food bank receded slightly as jobs started to recover from the pandemic, clients quickly came back because of inflation, Buffalino said. Food prices last year were nearly 24% higher than in 2020.

“It’s been a steady increase (in clients) over the past five years,” he said.

Farmers, too, will be affected by the grants’ cancellation.

The federal food-purchasing funds have allowed small farmers to buy new equipment, invest in greenhouses and expand their footprints to serve bulk buyers, said Megan Kenney of the North Coast Growers Association in Humboldt County.

Kenney coordinates food orders between two regional food banks and about 40 farmers, all of whom plant fewer than 100 acres each. Over the winter, she and the farmers planned what they would plant based on food bank demand, expecting federal funds to back the purchases.

“They were encouraged to do these sorts of things,” Kenney said. “If they have to make a larger investment into seeds or labor without getting to see a return, they could really see that impact.”

OBITUARY: Earlene Fisher, 1948-2025

LoCO Staff / Thursday, March 27, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

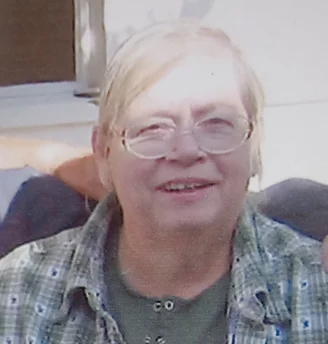

Earlene

Fisher, 77, passed away in her home in Eureka on March 16, 2025. She

was born on October 15, 1948 in Arkansas, the fourth of five children

of Pauline and William Cox. She is survived by her sister Linda

Ferdick of Merced, her nephew William Ferdick of Merced and numerous

other nieces and nephews throughout the U.S.

Earlene and her family moved frequently throughout Earlene’s childhood and in Planada, California, Earlene met and married her first and only love, Jerry Fisher, who had recently been honorably discharged from the army after service as a Ranger in Vietnam. The young couple settled in there and owned and operated a number of liquor and video stores for many years.

Earlene and Jerry fell in love with Humboldt County and decided to move to Eureka. In Eureka, they ran a Rental Property Service for many years until Jerry became ill and they sold the business so Earlene could care for him. Jerry died in 2012 from Agent Orange complications after 48 happy years of marriage.

For many years after Jerry’s death, Earlene managed the North Coast Standdown, helping veterans and their families by providing support, information and basic services. She also volunteered for many years at the Humboldt Senior Resource Center, where she made many friends who will sadly miss her.

Earlene was a light in the lives of all who had the privilege of knowing her. Her journey on this earth was one marked by love and compassion. Her passing has left a void in the hearts of her family, friends and the many whose lives she touched. We ask that you remember her not for the way her life ended, but for the way it was lived and for the impact it had on those who had the privilege of experiencing her generous and caring nature. You will be missed, Earlene!

A celebration of life will be held at a future date.

Anyone wishing to make a donation in Earlene’s memory might consider Hospice of Humboldt or the Senior Resource Center for their donation as well as any charity of their choice.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Earlene Fisher’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Jennifer S. Lenihan, 1967-2025

LoCO Staff / Thursday, March 27, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

It is with heavy hearts that we

announce the passing of Jennifer S. Lenihan, a beloved daughter,

sister, mother and grandmother. She was born on November 19, 1967,

and passed away on January 24, 2025, after a short battle with

cancer. Born in Petaluma, she resided in Eureka for the past

48 years.

Jenny attended Alice Birney Elementary, Jacobs Junior High, and Eureka High School. She worked in dietary services at Granada Wellness and Rehabilitation for many years, where she formed lifelong friendships. Her family is forever grateful to her Granada family for their willingness to provide comfort care if needed during her final days.

Jenny loved camping, spending time in Trinity Village swimming and relaxing, and taking spontaneous road trips. But more than anything, she cherished time with her family.

She is survived by her mother, Jeannette Lenihan; her daughter, Aimee Lenihan-Moorehead (Andrew Williams); her grandchildren, Aliana, Adaline, and Benjamin; and her longtime boyfriend, John McElroy, along with his daughter, Sarah, and grandson, Malikhi. She is also survived by her siblings and their spouses: Kathy Antongiovanni (Paul), Liz Greene (Gary), and Becky Beam (Rob); her nephews, Michael, Jeffrey, Matthew, James, and Dominic; her nieces, Allison and Kayla; as well as numerous aunts, uncles, cousins, great nieces and nephews. Two of Aimee’s siblings, Charlie and Kristina, held a particularly special place in Jenny’s heart.

Jenny was preceded in death by her grandparents, William and Elsie Hess and Raymond and Beverly Peterson; her father, Jeramiah Lenihan; her sister, Victoria Lenihan; and her nephew, George Foty.

The family would like to express their deep appreciation to Jenny’s Palliative Care Team for their compassion and kindness during this difficult time. We also extend our gratitude to the doctors and nurses at Providence St. Joseph Hospital who cared for her in her final days. A special thank-you to Cancer Crushers as well.

A Celebration of Life is planned — please reach out to the family for details. A private interment will follow. In lieu of flowers, please consider donating to the charity of your choice.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Jeninifer Lenihan’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.