St. Vincent de Paul’s Leadership Issues Urgent Call for Donations Amid ‘Severe Financial Shortfall’; Weekly Services Could Drop From Five to Three Days Per Week

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, March 4, 2025 @ 1:53 p.m. / Community Services

St. Vincent de Paul’s dining facility in Old Town Eureka. | Photo: Ryan Burns

###

Letter from the Society of St. Vincent de Paul - Redwood Region:

On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul’s Redwood Council, we are reaching out to the Humboldt County community with an urgent message. For 44 years, our Dining Facility has proudly served as safe haven to the displaced and low-income residents of northern Humboldt County, providing hot meals, clothing, hygiene kits, and access to essential services like healthcare, showers, and navigating shelter.

However, due to a severe financial shortfall during the past couple years, we are facing the heartbreaking possibility of reducing our service days from five to just three per week. This reduction would dramatically impact the individuals and families who rely on us for their daily nourishment and basic needs. Many of our guests face ongoing challenges, including behavioral health issues, prolonged exposure to dysfunction, or the overwhelming struggles of life on the streets. Our facility offers not just a meal, but a place of community, respite, and care.

The need for our services is greater than ever, and we cannot continue without the support of our community. We urgently call for donations, volunteer assistance, and spreading awareness to help us maintain our vital work. We have served over 3.5 million meals since 1981, but to continue our mission, we need your help.

We invite all community members to visit our Dining Room, located at 35 W. Third Street, Eureka, to see our work in action and experience the radical hospitality provided within our walls. We welcome everyone, which is rare in the modern world. Join us in our mission to create a safe place for the most vulnerable in our community. There is room for you at our table.

Please visit our website at svdp-redwoods.org to learn how you can make a difference, or email Bob Santilli directly at raps56@hotmail.com to see how you or your organization can contribute. Your support will ensure that we can continue to provide these essential services to those who need them most.

Thank you for your continued support.

Sincerely,

The Board of Directors

The Society of St. Vincent de Paul - Redwood RegionBob Santilli

Russell Shaddix

Georgeanne Fulstone-Pucillo

Stephanie Holmes

Juan Velazquez

Hannah Ozanian

###

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 8 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Sr162 / Biggar Ln (HM office): Trfc Collision-Unkn Inj

ELSEWHERE

Governor’s Office: Governor Governor Newsom proclaims Ronald Reagan Day

Governor’s Office: California celebrates 129 new CHP officers ready to protect and serve the Golden State

Governor’s Office: Governor’s Office demands Kristi Noem learn to Google before sending stupid letters: California works with ICE to deport criminals

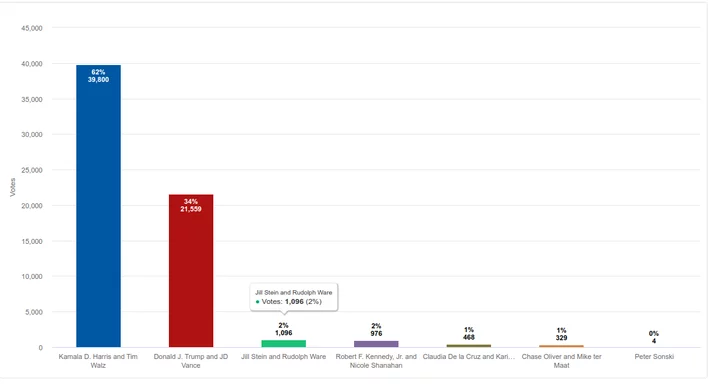

Check Out the Election Office’s Cool New Tool, Which Gives You a Billion Charts and Graphs to Show How Humboldt Voted

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, March 4, 2025 @ 12:13 p.m. / Elections

How Humboldt voted for president last fall. Click to enlarge.

Gone are the days of downloading PDFs. Press release from the Humboldt County Office of Elections:

The Humboldt County Office of Elections is proud to announce the launch of its new election results search tool, ElectStats, designed to provide voters and researchers with enhanced access to local election data.

ElectStats allows users to easily search and analyze election results through multiple entry points, including specific elections, individual contests and candidate names. This user-friendly system represents a significant upgrade from previous methods of accessing election data.

By offering immediate public access to historical election data, ElectStats helps reduce the time and staff resources needed to fulfill records requests, while empowering the public with detailed insight into the history of our local elections.

“This new search tool demonstrates our commitment to transparency and accessibility in the democratic process,” says Juan Pablo Cervantes, Humboldt County Registrar of Voters. “We’re making it easier than ever for our community to access and understand election results.”

ElectStats features:

Comprehensive search capabilities across all digitally archived election results.

Filter options by election date, contest type and candidate.

User-friendly interface designed for both casual voters and detailed research.

ElectStats is available today, Tuesday, March 4, and can be accessed through the Humboldt County Elections website at electstats.humboldtgov.org. Users will be able to search election results from 2013 to the most current General Election with older data to be included in the coming months.

For more information about the new search tool, please contact the Office of Elections by email at this link or by phone at 707-445-7481.

Police Reality TV Show ‘On Patrol: Live’ Has Wrapped Up Filming in Humboldt. What Did Sheriff Honsal Learn From the Experience?

Isabella Vanderheiden / Tuesday, March 4, 2025 @ 9:49 a.m. / Crime , Local Government

Source: “On Patrol: Live”

###

After spending nearly three months trailing on-duty Humboldt County Sheriff’s deputies, last month, camera crews with “On Patrol: Live” packed it in and headed home. For now, at least.

The sheriff’s office made its debut on “On Patrol: Live” — a reality TV show that follows on-duty police officers and sheriff’s deputies from departments across the United States — on Nov. 8. The show, which strives to give viewers a glimpse into the day-to-day duties of law enforcement officers, airs live (with a 10-minute broadcast delay) every Friday and Saturday night on Reelz, a digital cable and satellite TV network that offers an assortment of crime-related programming, including “Cops” and “Sheriffs of El Dorado County.”

Many of our readers will recall last year, when the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a one-year contract with the show’s production company, Half Moon Pictures, LLC, despite hesitation among some board members who worried the camera crews would distract deputies from their duties or cause reputational harm to the county. At that time, Humboldt Sheriff William Honsal made the case that the show would “highlight the professional law enforcement services” his deputies provide and, hopefully, improve recruitment for the department, which has been understaffed for years.

In a recent interview with the Outpost, Honsal said it’s “too early to tell” if “On Patrol: Live” has impacted recruitment, though he said the department is currently “near full staffing on the patrol side.” Still, he spoke favorably of the whole experience and praised the professionalism of the deputies who featured on the show.

“I feel like it was, overall, a great experience,” Honsal said. “[Our deputies] represented the county, they represented our department — and law enforcement in general — in a highly respectful manner. … You look at the professionalism [of departments] in other parts of the nation, you know, when it comes to how they handle people or patrol operations, and I’m just thankful to say that our deputies did it very, very well. … And the more people can see that, the more trust is garnered in our community.”

Asked how the sheriff’s office first caught the attention of the show’s producers, Honsal said he was approached in 2020 by the executive producers of “Live PD,” — a near-identical show dreamed up by the same production company as “On Patrol: Live” — at the beginning of the pandemic. (Perhaps they caught this episode of the Joe Rogan Experience?)

“[The producers] just saw how we were handling the pandemic … and kind of being the leaders of the community during the pandemic, and they thought it would be a good thing to highlight [HCSO] on ‘Live PD.’ I was starting to talk to [the producers] and then George Floyd happened at the end of May and all the protests [started],” Honsal said, referring to the national outrage over police brutality that followed the in-custody death of George Floyd. “At that point in time, ‘Live PD; was taken off the air by A&E, but I still kept in touch with [the producer].”

It didn’t take long for the show to make a comeback. “On Patrol: Live” premiered on Reelz just two years later. (Not long after the show premiered in July 2022, A&E sued REELZ for copyright and trademark infringement. The lawsuit was settled in October 2024.)

The HCSO made its debut on the program in November 2024 during a particularly slow time of the year, which is what ultimately led the department to take a break from the show.

“After about eight weeks, they wanted to continue [but] I said, you know, at this time of year, there’s not a lot going on and our guys are busy with training,” Honsal said. “I said we could use a break, and then we’ll come back and do the show again at the end of 2025. We’re looking at that as definitely a possibility.”

Looking through old episodes of “On Patrol: Live,” I noticed that the sheriff’s office didn’t get much airtime on the show, which seems to focus on the busiest departments in its lineup. During the first episode I watched, HCSO Deputy L. Bonilla is seen approaching a vehicle parked near the bathroom at the disc golf course in Manila where a man appears to be sleeping in the driver’s seat.

“It looks like he’s just dozing off, but [I’m] just gonna do a welfare check to make sure everything’s okay,” Bonilla tells the crew as he peers into the driver’s side window with his flashlight. “Usually, people come out here and [we] respond to people OD’ing.”

After confirming the man isn’t in distress, the deputy asks to see the driver’s ID, which he doesn’t have. The deputy then gives him a look and asks if he’s made contact with him before. “No, I don’t think so,” the man responds. The feed cuts and goes back to the “On Patrol: Live” studio where the show’s host, Dan Abrams, playfully asks his in-studio guests, “Do I know you from somewhere?” and the feed cuts to a police chase.

A little later in the episode, we see Bonilla approaching a silver SUV he’s just pulled over in the Eureka Wing Stop parking lot. As he walks up to the driver’s side window, a woman can be heard saying, “I was on the phone doing 20 things at once,” and he calmly tells her that she shouldn’t be on the phone while she’s driving.

She leans out the window, looks directly at the camera crew behind Bonilla, and asks if she’s on camera, accidentally handing him her debit card instead of her ID. “Oh my goodness, are we really on camera? Why?” she asks. The deputy asks her to move her vehicle to accommodate traffic trying to get into the parking lot, and the feed cuts again.

In another episode, HCSO deputies respond to a suspicious house alarm and, with the homeowner’s permission, take the camera crew through the house to ensure no one is hiding inside. The feed cuts to Richland County, S.C., where a man is being detained for letting his vehicle run while unattended in a gas station parking lot.

Honsal acknowledged that a lot of the content featured on the show is pretty routine stuff.

“Some of [the content] is the stuff that happens in between the calls for service, you know, when we’re stopping for a cup of coffee, talking with someone at a gas station or on the side of the road and they’re broken down,” he said. “There’s not police sirens or really anything exciting about that, but [it shows] the interaction and us treating people with respect and dignity. … I feel like that’s the side of law enforcement that a lot of people don’t understand. I think [the show] captures that well.”

How did local folks feel about their mugs being broadcast on national television? It’s difficult to say because we weren’t able to track down anyone willing to share their account.

I came across a post from an anonymous user on r/Humboldt who described their encounter with the “On Patrol: Live” crew after they were pulled over for a busted headlight. “The cop has a camera man with him, which weirded me out, but also the cop was acting hella intense for just a headlight, which seemed to … be because he was being filmed,” the poster wrote.

Other anonymous users in the comment section called the show “embarrassing” and asserted that it’s illegal for people to be filmed without their consent, which isn’t true. Others suggested that the sheriff’s office was just participating in the show for a little extra funding.

To be clear, HCSO was not paid for its participation in the show. The only money exchanged between producers and the departments featured on the “On Patrol: Live” is an insignia fee, which is usually paid directly to the city or county government that is hosting the show, as stated in the show’s FAQ section.

No money is paid by the producers to the departments in exchange for their appearance on ON PATROL: LIVE. Committing to a season of ON PATROL: LIVE can be demanding on a department’s resources, especially for smaller agencies. In an effort to make a department’s appearance on ON PATROL: LIVE cost-neutral for taxpayers, and upon discussions with the department regarding their specific needs, the producers employ the industry-wide practice of paying a nominal Insignia Fee, which is a standard television licensing practice involving a specific payment for the rights to air an agency’s name or logo. Frequently, Insignia Fees are paid directly to the city government, not to the police department itself.

[ADDENDUM: In an emailed response to the Outpost’s previous inquiry about insignia fees, HCSO Spokesperson Meghan Ruiz said the sheriff’s office has not taken any fees from the show to date.]

Honsal couldn’t say for sure if and when “On Patrol: Live” would return to Humboldt County, but if it happens, it would probably be sometime in the fall.

“We still have an active marijuana season, and there’s definitely things that occur during harvest season — whether it’s robberies [or] violence — where we just have an uptake in crime in general,” he said. “It’s an up in the air thing, but [the producers] know they are welcome back here.”

###

PREVIOUSLY:

‘Too Damn Hard to Build’: A Key California Democrat’s Push for Speedier Construction

Ben Christopher / Tuesday, March 4, 2025 @ 7:49 a.m. / Sacramento

Framers work to build the Ruby Street apartments in Castro Valley on Feb. 6, 2024. The construction project is funded by the No Place Like Home bond, which passed in 2018 to create affordable housing for homeless residents experiencing mental health issue

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

A California legislator wants to solve the state’s housing crisis, juice its economy, fight climate change and save the Democratic Party with one “excruciatingly non-sexy” idea.

Oakland Democratic Assemblymember Buffy Wicks sees the slow, occasionally redundant, often litigious process of getting construction projects okayed by federal, state and local governments as a chief roadblock to fixing California’s most pressing problems, from housing to water to public transportation to climate change.

Last year, Wicks helmed a select committee on “permitting reform” — a catch-all term for speeding up government review at all stages of a project’s development, not just its literal permits. The committee went on a state-hopping fact-finding mission, taking testimony from experts, builders and advocates on why it takes so long to build apartment buildings, wind farms, water storage and public transit, to name a few notoriously slow and desperately needed project types.

Today, that committee released its final report. The summary, per Wicks, is that “it is too damn hard to build anything in California.”

The report stresses the need for the state to build millions of new housing units and electric vehicle chargers; thousands of miles of transit; drought, flooding and sea level rise projects; and renewable energy projects “built and interconnected at three times the historical rate.”

Though the jargon-laden technical analysis isn’t likely to go viral, the report tees up what could be one of the biggest legislative battles of the coming year. Wicks said lawmakers in both chambers are hammering out 20 bills on permitting snags for housing construction alone. Other bills to speed approvals for transit, clean energy and water projects are reportedly in the works too.

Lawmakers regularly pass one-off bills aimed at making it easier for favored projects to get built. Nearly every legislative session for the last decade has seen at least a handful of “streamlining” bills for dense housing.

This political moment may be primed for something bigger, said Wicks. In the capitol, an aggressive red-tape snipping mood seems to have set in. More California officials, especially in Los Angeles and especially in the wake of January’s wildfires, want to re-examine how buildings get permitted.

President Trump’s unambiguous, if modest, electoral victory in November, riding a wave of public anger over Biden-era inflation, has pushed many Democrats to reorient their policy platforms toward cost of living issues.

Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas, a Salinas Democrat, kicked off this year’s legislative session by urging lawmakers to “consider every bill through the lens” of affordability. Gov. Gavin Newsom more recently acknowledged “the inability of the state of California to get out of its own way” on big, important projects. He suspended certain environmental regulations for fire prevention projects last Saturday.

In California and across the country, concurrent housing and climate crises have convinced many lawmakers and Democratic-leaning policy commentators to prioritize building lots and lots of things: apartment buildings, EV charging stations, electric transmission lines, solar and wind farms, rail lines and bus networks. The quicker the better.

The catastrophic Los Angeles firestorms from January highlighted just how difficult it can be to rebuild. Newsom has named cutting environmental regulations and speeding up entitlement and permitting processes in the burned areas as his top priority.

In Sacramento, a new batch of state lawmakers, elected partly by mad-as-hell voters and unscarred by past legislative battles over permitting changes, may be newly receptive to making big changes too.

“All of that combined makes, I think, a unique opportunity for us to actually have some pretty significant change,” said Wicks.

The report itself does not offer precise recommendations, but its analysis is often tellingly specific, offering clues about the changes that lawmakers can expect to debate this spring.

Described as “opportunities for reform,” these are, in Wicks’ words, often “excruciatingly non-sexy.” For example, the report notes that lawmakers could be more specific about when a certain type of housing application is deemed “complete” in order to shield developers from future legal changes. Another “opportunity”: Allow for third-party experts to sign off on a project’s plans.

Current policies that could be a template for regulatory revamping, according to the report: the state’s bolstering of accessory dwelling units, electric vehicle charging stations and certain environmental restoration projects.

But those “success stories” share a trait that points to what could be the most contentious aspect of the coming legislative package. All three are exempt from the California Environmental Quality Act, a 1970 law that requires governments to study and publish findings on the environmental impact of any decision they make, including the approval of new housing, transit or energy projects.

The act, pronounced see-kwah, is among the most fiercely debated in California politics. Opponents contend that the law is regularly hijacked by special interest groups, such as NIMBY property owners or organized labor unions, to stall projects for decidedly non-environmental reasons. They point to high profile court battles as examples of the act’s abuse, such as the case resolved by the state Supreme Court last year in which Berkeley neighborhood groups argued that the noise predicted to come from college student housing amounted to a pollutant under the law.

“If we want to reach our climate change goals, CEQA needs to be reformed,” Wicks said. “If we want to reach our housing goals, CEQA needs to be reformed.”

Defenders of the law say it is vital to deliberation, public input and transparency, keeping local and state governments and developers from running roughshod over vulnerable communities.

“Sometimes, for vulnerable communities, the act is the only tool available to have a seat at the decision making table,” said J.P. Rose, a policy director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “To brush all of that aside to say ‘that’s just permitting,’ I think that’s a misguided lens to address this issue.”

Lawmakers often carve specific exemptions into the law, but historically, making across-the-board changes to CEQA has been a heavy lift in Sacramento. Two years ago, Newsom rolled out plans to overhaul the law in order to speed up the approval of big, infrastructure projects. Many of its most ambitious proposals were sidelined. Last year, the Legislature tried to rush through a bill aimed at getting clean energy projects up and running more quickly (it failed).

“Right now, there are too many opportunities in the process to put a wrench in the gears.”

— Buffy Wicks, Assemblymember, Oakland

Lawmakers are likely to spend plenty of time arguing about the act, no matter what happens to the permitting package. One bill, already in print, by San Francisco Democratic Sen. Scott Wiener, would make it easier for urban housing projects to exempt themselves from the law and for local and state governments to avoid having to conduct full environmental reviews for every aspect of each project. The senator dubbed it “the fast and focused CEQA Act.”

Rose, at the Center for Biological Diversity, said the bill “fires a shotgun at the heart of CEQA.”

Carter Rubin, a public transportation advocate with the Natural Resources Defense Council who testified to the select committee last year, said there ought to be a difference between the way regulators review projects that help achieve the state’s housing and climate goals and those that emphatically do not.

“We certainly would not support streamlining highway expansion or sprawl development that impacts ecosystems,” he said in a phone interview. “It’s really important that the Legislature focuses on shovel-worthy projects, not just shovel-ready projects.”

Wicks said she will put forward a housing bill on CEQA as part of the overall package.

“Right now, there are too many opportunities in the process to put a wrench in the gears,” she said. “There will be a cost for us Democrats on the ballot in the future if we don’t fix that problem.”

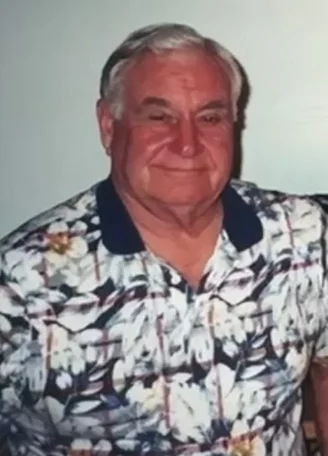

OBITUARY: Frank Hizer, 1934-2025

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, March 4, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Frank George Samuel

Hizer III, 90 years young, passed away peacefully at home on January

27, 2025, with his wife, Linda, by his side. Frank was in charge all

the way to the end and left on his terms. He knew his body couldn’t

handle much more and Hospice was coming that day, so he made a quick

departure.

Frank was born in Hayward to Myrtle and Edgar Hizer. He had one older sister, Vonda. His father was a logger in the Placerville/Sierra Nevada area and his mom ran their logging camp kitchen. Frank said his family moved once or twice a year, and that he went to at least 13 different schools growing up. He said he didn’t like school much and never had much of a chance to make friends. When his family moved to Fieldbrook, he did his senior year at Arcata High. It was there that he made several lifelong friends within his Class of ‘52. Up until last Spring, there were 10-15 of them meeting for monthly luncheons.

While at Arcata High Frank met his first wife Shirley Luster. After graduation, Frank enlisted in the Navy, married Shirley, and they had daughter Donna in 1955 and son Joseph in 1957 while he was stationed in San Diego on the USS Sperry. He also took Navy courses to become a Master Welder. His love for welding stayed with him throughout his life. After the Navy, Frank, Shirley and kids moved back to Fieldbrook and he got a job as a welder with the PG&E nuclear plant at King Salmon. He worked there for a while but said it was too restrictive and he found himself in trouble numerous times with the Union for helping his fellow workers whenever he had extra time. That was just who Frank was. He loved helping people.

A few years later, Frank moved his family down to Fortuna and opened Fortuna Wheel and Brake in 1961. He spent the next 50 years being a successful businessman and doing what he loved: working on cars, recapping tires, outthinking anything mechanically broken, building a roadster and stock and drag cars. So many people either worked for or hung out at Frank’s shop. Lots of afterhours projects were built there too. Friendships were made, and friends became family. Many looked up to him as a father, and a few still call him Dad.

Family was very important to him. He and Shirley were married 30 years and remained friends after they divorced. As a young family, they were involved with many activities: raising & showing horses professionally, softball, football, wrestling, house boating, water skiing, and Stock Car & Drag Racing.

As a grandfather, he continued the same dedication; traveling to Redding to as many events as possible to watch his granddaughter Hilaree, later to UNLV for her graduation. He traveled to Pensacola, FL to stand with his Grandson Ivan while getting his Navy Wings. He enjoyed talking with them and hearing about their lives.

In his spare time Frank kept busy joining local clubs, leagues, and organizations-Jaycees, Toast Masters, Bowling, Straight-A-Ways Car Club, FUHS Board, and the Rodeo Board. He played a key role in starting Fortuna’s Pop Warner Football, which is now ERV Youth Football. He loved that chapter in his life. He spent many years being involved with the local youth and coaches teaching teamwork and respect. In 1965 he joined the Fortuna Volunteer Fire Department, Company 3 Hook and Ladder. He was dedicated to the department for 43 years, serving the last several years as Assistant Chief and Chief.

Another big piece of Frank’s life was creating the Fortuna Redwood AutoXpo Car Show. He said it got its start when the High School asked for his help in putting together a car show one year. An idea was born! As the story goes, he got together with a few friends and a six pack of beer and started brainstorming. From there it just kept growing each year. Now 34 years later, it’s one of the most popular car shows around. Frank stepped aside as President in 2017 but remained an important member on the committee.

Frank truly loved Fortuna and Fortuna loved him too. He was Citizen of the Year in 2002, awarded Fireman of the Year in 2005, and Rodeo Parade Grand Marshal in 2006.

Frank worked hard and played harder. In his downtime, Frank was the life of any party going on, and even if you couldn’t see him, you could hear his distinct laugh rise above the crowd. He was usually with his best friend Joe, having a cocktail or two, and between the two of them they would find lots of good-humored mischief. He also loved watching sports, horse racing and NASCAR.

In the spring of 1999 Frank met his second wife, Linda. They spent the next 25 years building a wonderful life together traveling to different places, always finding a flea market or casino; dancing; laughing; helping at the Elks Lodge; annual Reno Bus Trips; traveling to family events, which usually involved a game of Pinochle; moving to Hydesville where they kept busy with a variety of hobbies, ranch life, including raising mini donkeys; and mostly enjoying each other’s company. That incredible bond got them through the many tough times that were to come.

Frank was one of the toughest people around. He fought a long uphill battle after finding out in 2016 that he was in kidney failure caused by a rare immune disease, Wegener’s Granulomatosis, a vascular disease that can affect any or all organs. By the grace of God, we were blessed with Dr. Mathew. With the knowledge and dedication of him and his staff at Redwood Renal and Eureka Dialysis Clinic, Frank had eight more years with us.

Frank is preceded in death by his parents, Myrtle & Edgar; daughter, Donna; in-laws, Dorothy & Jess Luster; sister, Vonda; brother-in-law, Larry; sister-in-law, Karen; father-in-law, Robert; #2 son Emil & wife Mary Ann; several cousins, a nephew, and many close friends.

He is survived by his wife, Linda; son, Joseph (Nadya); granddaughter Hilaree (Steven); great-grandchildren Brayden & Kayleigh; grandson, Ivan (Becca); former wife, Shirley; son-in-law Gary (Karen); sister-in-law, Annette; #2 daughter, DeDee (Shannon); best friend, Joe; several nieces & nephews; and many close friends.

We will be having a celebration of life on Saturday, April 19, 2025 at Fortuna Veterans Memorial Hall, starting with a Fire Truck Procession at 12:30 p.m. A Memorial Service will follow at 1 p.m. Food and drink will be provided. Frank requested we make this a happy occasion and celebrate a life well-lived. Feel free to wear cheerful colors and bring a story to share.

If you are unable to attend, please raise a glass wherever you are and tell a Frank Story, hug your family & friends, or do something nice for someone.

In lieu of flowers, please make any donations in memory of Frank to: Fortuna Volunteer Fire Department, ERV Youth Football, or Fortuna Redwood AutoXpo.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Frank Hizer’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

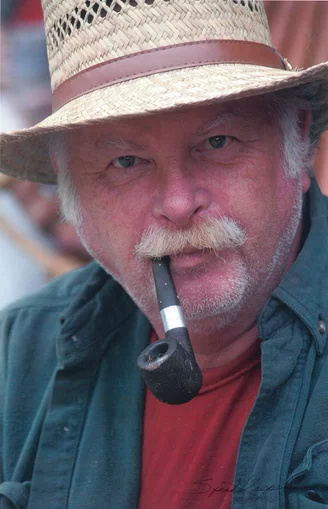

OBITUARY: Daniel Steven McClelland, 1949-2025

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, March 4, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Daniel Steven McClelland

June 2, 1949 – January 19, 2025

Dan was born at St. Joseph Hospital in Eureka to Kenneth Lindsey McClelland and Fannie Faye McClelland (nee: Gray). He was the second of three children with an older brother, Michael and younger sister, Pam.

Dan had an active and happy childhood in Loleta. Dan spent his days visiting his Grandma and neighbors, running around outside and raising animals. His childhood was filled with hunting and fishing with his family. Christmas Day was reserved for hunting. Dan spent summers at the Hough Ranch playing, later as he grew older, working.

Dan graduated from Fortuna High School in 1968 and then College of the Redwoods with an Associate Degree in General Education. During the summer breaks at college, Dan worked on a commercial tuna fishing boat.

During this time Dan and his family unexpectedly lost his mother, Faye. Years later, Dan’s father, Ken remarried, and Dan gained three stepsiblings, Cheryl, Karen, and Gary Battaglia.

After college, Dan joined the Mel Reese Construction crew. Eventually, Dan became a business owner himself, starting Dan McClelland Construction.

Dan met his lovely wife, Loene Gossett, while working backstage at the first Junior Miss Pageant put on by the Jaycees in Fortuna. She was the contestants’ choreographer. Their first date was at Parlato’s restaurant. Dan and Loene were married on July 2,1978 at the Fortuna United Methodist Church.

Dan became close to his in-laws, Gwen and Ernie Gossett. Frequently visiting with them after work to have coffee, and play cards while Loene was teaching dance or at rehearsals with the Redwood Concert Ballet. Sunday family dinners were a regular occurrence. Ernie introduced Dan to the Masonic Lodge which became an important pillar in Dan’s life dedicating himself to the good works done with his brothers in the lodge. He was a multi-time past master, was awarded the Hiram Award, Mason of the Year twice and was a 32nd-degree Master Mason. In Scottish Rite he was elevated to Knights Commander of the Court of Honor. Dan treasured his brother Masons. The friendship and brotherhood they shared was a core of Dan’s daily life.

Dan and Loene were blessed with their son, Luke, in 1981 and daughter, Damaris, in 1985. Dan was active in his children’s lives. He was a Pack Leader and Boy Scout leader. He and Luke were honored with the Order of the Arrow while in Boy Scouts. They also participated in 50-miler hikes with the Boy Scouts. He took his Scouts to the beach and camping and would regale them with stories.

In the 1990s Loene convinced the family to go to the Jed Smith Mountain Men Tall Trees Rendezvous in Smith River.. This yearly camping excursion during the July 4th week invigorated Dan’s love of black powder shooting, but also included cast iron cooking, archery, and knife and hawk (tomahawk) throwing, amid this 1815-era mountain men’s gathering. The family went every year after that. Last July, their grandchildren and four other teens and young adults went.

When Lucas had children, Dan became “Poppy.” Dan loved being “Poppy” and was involved in his grandchildren’s lives.

He loved to cook and experiment in the kitchen, putting food together because it sounded good. He was also very artistic. He carved wooden sculptures and made beautiful wooden boxes and furniture.

Dan was an avid outdoorsman. He continued to hunt and fish throughout his life with many friends and family. Special thanks to Rex Hunt and family, Phil and Jay Grunert, Phil Acott who were deeply tied to his hunting and fishing and considered good friends. His Sunday Skeet Shoots with the Masons and his other friends and his puppy, Sophie, were weekly activities.

Every morning Dan would step outside the front door with his dog, soak up the morning sun, come in and say “Ah, Life is good!” with a smile on his face.

Dan is survived by his beloved wife, Loene Gossett, son Luke and partner, Alyssa Owens, his daughter Damaris and granddaughters, Michelle and Marine McClelland, sister and her husband Pam and Parviz Sadrian, sister and brother, Karen and Gary Battaglia, Brother-in-law and wife, Ernie and Bridget Gossett and their daughters, Denice Taylor, her husband Seth and their children, Nicole Robinson and her partner, Kurt Williams, nephews, Bob Lyness, Bob Angelini and wife, Terri and their family, nephew-in-law, Mike Flockhart and family, cousins Dennis and wife, Catherine, Rob and wife, Karen, and Marty McClelland, Kathy and husband, Dale Moore and their families.

Dan was preceded in death by his mother, Faye McClelland, father, Ken McClelland and brother, Mike McClelland, mother and father-in-law, Gwen and Ernie Gossett, sister, Cheryl Battaglia, and niece, Lynett Flockhart.

A memorial and celebration of life will be held on April 12, 2025, at 2 p.m. at the Fortuna United Methodist Church.

In lieu of flowers, Memorial contributions may be made to the Valley of Northern California Scottish Rite Childhood Language Center; C/O Eel River Empire Lodge #147 F&AM; PO Box 51; Fortuna CA 95540

Or

To the Redwood Shrine Club for Shriner’s Hospital Transportation Fund; 251 Bayside Rd; Arcata CA 95521

Or

To a favorite charity.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Dan McClelland’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Virgil Kirkpatrick, 1940-2025

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, March 4, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

It is with the heaviest of hearts that we announce the passing of Virgil Kirkpatrick. He passed away peacefully on February 14, 2025 at Hospice House, Hospice of Humboldt. Virgil was surrounded by loved ones in the days and hours preceding his death.

Virgil was born in Marysville to Robert and Pearl Kirkpatrick and raised in the foothills of Yuba County. Virgil was the third of five children. Virgil joined the US Army in 1961 and was honorably discharged in 1964. Virgil married and had three children — Robert, Kathy and Gaylene. He brought his family to Humboldt County in the early 1970s. He later divorced and found and married his soul mate Letha Kirkpatrick. Virgil and Letha were married in May 1976 and lived in Fieldbrook, where they raised their children.

Virgil was a fan of football, especially the San Francisco 49ers, and NASCAR. Virgil was an avid Bill Elliott fan and when Bill Elliott retired, he became a fan of Bill Elliott’s son Chase Elliott.

Virgil is preceded in death by his father, Robert Kirkpatrick, mother, Pearl Kirkpatrick, sisters Barbara and Pat and his brother Dennis. Virgil is survived by his wife Letha Kirkpatrick, sister Nadine Stiles, children Robert, Kathy and Gaylene, step-children Debbie, Donna and Kathy and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren, as well as many nieces, nephews, great nieces and great nephews, friends and neighbors.

To know Virgil was to love him. Virgil was kind, compassionate, loving and forgiving. He loved his family deeply and would do anything within his means for those he loved.

There will be a graveside service at Ocean View Cemetery, 3975 Broadway St, Eureka, CA 95503 on March 14, 2025 at 1 p.m. A celebration of life will immediately follow at a location that is to be determined. In lieu of flowers, please make a donation to Hospice of Humboldt in Virgil’s name.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Virgil Kirkpatrick’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.