THIS WEEK IN SUPES: Grand Jury Recommendations for Aging County Facilities, Leased Properties, Civilian Oversight of Sheriff’s Office

Isabella Vanderheiden / Monday, Aug. 12, 2024 @ 7:41 a.m. / Local Government

Photo: Andrew Goff

The Humboldt County Board of Supervisors will return to the dais Tuesday after a little summer vacation. What’s on this week’s agenda, you ask? Let’s have a look.

Civil Grand Jury Recommendations

The board will review and respond to recommendations made in two recent reports from the 2023-24 Humboldt County Civil Grand Jury concerning county facilities.

In the first report, “Humboldt County Facilities: Owning vs. Leasing,” the Civil Grand Jury analyzed the county’s real estate portfolio and determined that the county pays too much in rent – over $556,000 per month. The county currently has over 80 active leases across the county, some of which are “net” leases, meaning the county pays the property taxes, not the property owner, adding another $9,000 to the monthly total.

The Civil Grand Jury’s report asks: “Would the money be better spent in the long run by owning these facilities instead?”

“The County currently leases more properties than they own,” according to the report. “Fifty-three percent of the buildings used are leased, not owned. Long-term leasing tends to be more expensive than building and owning facilities. The trend towards leasing has not been cost-effective for the citizens of Humboldt County. … Most of the leased properties have been under lease for 25 years or more by the County.”

The report also suggests that the county could save money by consolidating some of its facilities. The 2020 Facilities Master Plan calls for building and consolidating operations. However, the Civil Grand Jury says “progress has been slow.”

“Consolidating County operations into fewer buildings can lead to greater efficiencies,” the report continues. “The County provides services to residents all over the county, so consolidation is not a viable option everywhere, but it is in Eureka, where the County operates in almost 50 different sites.”

Most of those sites are occupied by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), which actually consolidated some of its family-serving operations at Humboldt Plaza ten or so years ago. Doing so “improved customer service” at DHHS because residents were able to “accomplish more in a single stop at a facility that is easily accessible by car or public transit.”

Combining operations into fewer buildings would also “allow for better communication” among staff and “ease daily operations between agencies.”

The report includes three recommendations:

- To update the Facilities Master Plan by Mar. 31, 2025, to incorporate achievable implementation goals.

- By no later than July 1, 2025, to evaluate funding alternatives for future property acquisitions.

- To accelerate consolidation of county operations rather than leasing new facilities.

The second Civil Grand Jury report, “Humboldt County Custody & Corrections Facilities,” calls for upgrades to several aging county facilities, including the jail and juvenile detention center, the animal shelter, Sempervirens Psychiatric Health Facility, the Coroner-Public Administrator’s office, as well as the state-run Eel River Conservation Camp and the Sheriff’s Work Alternative Program (SWAP).

“We observed common issues at several facilities including serious needs for repairs, maintenance and upgrading of buildings,” the report says. “Some physical structures are relatively new. Others are many decades old. Despite these conditions, facilities appear to be functional and serviceable. … We also noted significant understaffing, leading to substantial amounts of required overtime. These issues, along with working in already stressful positions, lead to staff fatigue.”

The 2022-23 Civil Grand Jury issued a similar report – “Custody and Corrections, and Other Humboldt County Facilities” – that called out “appalling and dangerous conditions” at the animal shelter. The county’s responses to the report were “positive in terms of making changes to address problems,” but some of the recommendations still haven’t been implemented. “In some cases, the issues already documented have become worse because of delayed actions.”

The Civil Grand Jury issued the following recommendations for each of the facilities in question:

- Humboldt County Animal Shelter: To repair the roof and repair or replace inoperable outside lights by Oct. 31, 2024.

- Eel River Conservation Camp: To ensure that all fire safety equipment and facilities are in working condition by Nov. 30, 2024.

- Humboldt County Juvenile Detention Center: To adjust the pay scale for juvenile correctional officers by July 1, 2025, to be more competitive with correctional deputies. To coordinate with Public Works to install a rain gutter “above the walkway by the grass area” by Oct. 1, 2024.

- Humboldt County Jail: To repair leaks in the roof by Dec. 31, 2024. To repair or replace “the padded parts of the wall-mounted parallel bar exercise equipment” by Oct. 31, 2024.

- Humboldt County Coroner-Public Administrator: To create a policy and procedures manual for the coroner’s portion of the position by Dec. 31, 2024. Install a keypad lock on all doors accessing areas of the office that store property or evidence by Dec. 31, 2024. To develop or purchase a computer system to inventory and trace deceased people’s personal property (not criminal evidence) by July 1, 2025. To repair walls in the evidence room to protect exposed electrical components by Dec. 30, 2024. To replace all work surfaces in the autopsy room with stainless steel by June 30, 2025.

- Sempervirens: To fill “at least half” of the vacant positions at the facility by Jan. 1, 2025.

- SWAP: To install a secure fence with a locked gate around the drainage pond by July 30, 2025. To adequately staff the SWAP Farm with a minimum of six deputies by Dec. 31, 2024.

The board will also return to the topic of oversight of the Sheriff’s Office. During its July 23 meeting, the board discussed the formation of a civilian oversight committee, as recommended by the Civil Grand Jury, to enhance transparency within the department. The board was divided on the topic and, without Humboldt County Sheriff William Honsal present for the discussion, decided to revisit the topic at a future meeting.

The board will discuss the Civil Grand Jury’s recommendations for each report during Tuesday’s meeting. County department heads will likely weigh in as well.

###

Those are the big-ticket items on this week’s agenda. The county’s agenda management system is on the fritz this week, which means our AgendaBot Gennie won’t be able to deliver summaries and clever renditions of each agenda item that we’ve all come to know and love. Sad. Maybe next week.

The Board of Supervisors will meet Tuesday at 9 a.m. in board chambers at the Humboldt County Courthouse – 825 Fifth Street in Eureka. Click here for the full agenda.

BOOKED

Yesterday: 9 felonies, 9 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Brr! Storm System to Bring Heavy Rain and Lower Snow Levels Across Northwest California

RHBB: Snowpack in Klamath National Forest Well Below Average After Dry Winter Start

RHBB: Major Roadwork Scheduled Friday February 13 through Thursday, February 19

RHBB: Six Rivers National Forest Hiring Seasonal Recreation Workers

‘We Gotta Be Somewhere’: Homeless Californians React to Newsom’s Crackdown

Marisa Kendall / Monday, Aug. 12, 2024 @ 7:24 a.m. / Sacramento

Coral Street in Santa Cruz has become a prominent hangout for the unhoused community, who find resources at the Housing Matters shelter during the day. Aug. 7, 2024. Photo by Manuel Orbegozo for CalMatters

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s message on homelessness in recent weeks has been clear: The state will no longer tolerate encampments, and cities shouldn’t either.

Californians who live on the streets, as well as the outreach workers who support them, say they’re already feeling the difference. Places where someone used to be able to pitch a tent and sleep in peace have suddenly become inhospitable. Police seem to be clearing camps more often and more aggressively, and are less likely to give advance notice before they come in with bulldozers and trash compactors, according to anecdotal reports in some cities. Even in cities where officials said publicly nothing would change, unhoused people and activists say it’s become harder to be homeless.

But the shift, sparked by a Supreme Court ruling and then further fueled by an executive order, hasn’t caused a significant increase in shelter beds or affordable housing.

That’s led people on the streets to ask: Where are we supposed to go?

“We gotta be somewhere,” said Tré Watson, who lives in a tent in Santa Cruz, and says unhoused people are running out of places to go. “We can’t hover. We come here, they run us away. We go to any park and they run us away. We go to the Pogonip (nature preserve), and they bring bulldozers.”

Tré Watson outside the Housing Matters shelter in Santa Cruz on Aug. 7, 2024. Photo by Manuel Orbegozo for CalMatters

Homeless Californians and activists from San Diego to Sacramento told CalMatters that enforcement has become more frequent and more aggressive. Some city leaders have made their intentions to ramp up enforcement explicitly clear. The Fresno City Council recently passed an ordinance, which, if it gets final approval later this month, will make it illegal to camp on public property at all times. San Francisco Mayor London Breed said the city will launch a “very aggressive” crackdown, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

Others have said they won’t make changes to their encampment strategies. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors last month reaffirmed that the county won’t use its jails to hold homeless people arrested for camping, the Los Angeles Times reported. Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass also has been critical of criminalizing public camping.

Newsom pushes for a crackdown on homeless encampments

Homelessness has been a defining obstacle of Newsom’s career ever since he was mayor of San Francisco in the early 2000s. And it’s only become more pressing — California’s estimated homeless population has swelled to more than 181,000, at the same time Newsom is widely rumored to have presidential ambitions.

Earlier this summer, the conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court handed cities a new cudgel to crack down on the encampments that proliferate across California’s parks, sidewalks and open spaces. Per the Grants Pass v. Johnson ruling, law enforcement can now cite or arrest people for sleeping on public property — even if there are no shelter beds available to them. That’s a major change from prior legal precedent, which said it was unconstitutional to punish someone for sleeping outside if they had nowhere else to go.

Roberta Titus, 67, sits outside a juice shop on Front Street in Santa Cruz on Aug. 7, 2024. Photo by Manuel Orbegozo for CalMatters

A month later, Newsom responded with an executive order directing state agencies to ramp up enforcement against encampments, and encouraging cities to do the same. The order didn’t technically require cities to act, but last week, Newsom made it clear there will be consequences for cities that don’t.

If he doesn’t see results in the next few months, and if he doesn’t feel local leaders are acting with a “sense of urgency,” he’ll start redirecting their funding, Newsom said during a news conference outside a homeless encampment in Los Angeles.

“We’re done with the excuses,” he said. “And the last big excuse was, ‘Well, the courts are saying we can’t do anything.’ Well, that’s no longer the case. So we had a simple executive order: Do your job. There’s no more excuses.”

The state agencies that will be most immediately affected by Newsom’s order — Caltrans, California State Parks and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife — did not answer questions requesting details about how the executive order will change how they clear encampments on their property, nor did they provide data on their prior abatement efforts. State Parks referred questions to the governor’s office, which did not respond.

What it’s like for homeless Californians

In Santa Cruz, enforcement has become particularly “brutal” in recent weeks, said Keith McHenry, an activist who hands out food and other supplies to homeless communities through his organization Food Not Bombs. Though, as in many cities, it’s hard to tell how much of the change is a direct result of the Supreme Court decision and executive order. The tide already was shifting toward enforcement before the justices ruled.

In April, Santa Cruz pushed between 30 and 40 people out of a major encampment in a community park, according to the city. Many of the people displaced from the park then set up tents on Coral Street, outside the local homeless shelter, McHenry said. The city cleared that camp in June. After those sweeps, some people relocated to the Pogonip nature preserve at the edge of the city. Late last month, the city swept the nature preserve.

“We can’t hover. We come here, they run us away. We go to any park and they run us away. We go to the Pogonip (nature preserve), and they bring bulldozers.”

— Tré Watson, resident, Santa Cruz

The city says just five people were removed from the Pogonip in that sweep, but McHenry suspects it was more.

The city says its strategy for dealing with homeless camps hasn’t changed.

“The City’s current practices have proven effective and are already consistent with Governor Newsom’s suggested encampment-related policies for local governments contained in his recent executive order,” city spokesperson Erika Smart said in an email.

First: Spraq, 46, stays with his dogs and a partner in a small camp outside the Housing Matter shelter. Last: An eviction notice on a tent set up on Pacific Avenue. Santa Cruz on Aug. 7, 2024. Photos by Manuel Orbegozo for CalMatters

A group of unhoused people camp outside the Housing Matters shelter in Santa Cruz on Aug. 7, 2024. Photo by Manuel Orbegozo for CalMatters

On a recent Wednesday morning, a man who goes by the nickname Spraq was packing his belongings onto a bike trailer, preparing for the sweep he thought might come later that day on Coral Street. Spraq, who ended up on the streets after the truck he was living in got repossessed about 10 years ago, was camping in the park until police kicked everyone out. He and his ex-girlfriend moved to a nearby street, and two days later, police found them, threw away his ex’s clothes and other possessions, and forced them to move on, Spraq said. So they moved into a parking spot on the street outside Costco – a place where they’d camped without issue many times before, he said. Again, police found them, said they couldn’t be there, and threw away their belongings, Spraq said.

“They kept doing that until we had nothing,” he said.

Combined, McHenry says the recent sweeps mark the biggest push to dismantle encampments that he’s seen in Santa Cruz in years. Before, he said, people would relocate after a sweep and the city generally would leave them alone for a while. This time, police have been coming back regularly to spots like Coral Street to make sure people don’t return, he said. The city recently erected a chain-link fence and orange, plastic barricades along the sidewalk to deter campers.

“There’s just a full-court press to keep people from being settled anywhere,” McHenry said.

Cities respond to Newsom’s push for a crackdown

Enforcement seems to be ramping up along the bank of the San Diego River, where about 300 people live in tents and make-shift shacks — many of whom ended up there after police kicked them out of other camps closer to town, said Kendall Burdett, an outreach worker with the nonprofit PATH. Lately, the authorities have been clearing camps along the river multiple times per week, Burdett said. Before Newsom’s executive order, sweeps happened closer to a few times a month, he said.

The riverbank includes land controlled by Caltrans and by the city, and it’s not always clear who is sweeping camps, Burdett said. But he said he’s noticing the authorities are less likely to give advance notice before sweeping, leaving him and his co-workers scrambling to help their clients. That’s making it harder to get people into housing, Burdett said. People often lose their identifying documents in sweeps — which they need to get into subsidized housing.

“That sets the whole thing back,” he said.

Other times, Burdett can’t find clients after they’re swept. As a result, sometimes clients end up losing their housing placements.

“The last big excuse was, ‘Well, the courts are saying we can’t do anything.’ Well, that’s no longer the case. So we had a simple executive order: Do your job. There’s no more excuses.”

— Gov. Gavin Newsom

San Diego already had been ramping up enforcement, passing an ordinance banning encampments in certain areas last year. But the city says recent developments have changed nothing.

“There has been no change or move to increase abatements after the Supreme Court decision or following Newsom’s executive order,” city spokesperson Matt Hoffman said. “It’s just business as usual as of now.”

In San Francisco, where Mayor Breed promised an aggressive crackdown following the court ruling, the city removed 82 tents and five other structures from the streets the week of July 29 through Aug. 2. Abatement teams engaged with 326 people during those operations — 38 of whom accepted a shelter bed — and arrested or cited nine people, according to the city.

Other cities are passing or considering new, more punitive rules as a result of Newsom’s executive order. In Fresno, the City Council granted preliminary approval last month to an ordinance that would ban camping on public property at all times, the Fresno Bee reported. Fresno County approved a similar measure.

An unhoused person on a kayak in the San Diego River on March 23, 2024. Photo by Kristian Carreon for CalMatters

Stockton Mayor Kevin Lincoln said on Twitter the city must “move urgently” to ensure public safety while also supporting those in need. He made plans for a public study session later this month to discuss how the city will enforce anti-camping ordinances going forward.

In Sacramento, the city is distributing fliers to educate its unhoused residents about the changes under the Supreme Court ruling. The light-blue notices, titled “Attention: Unlawful Camping,” warn that people can be charged with a misdemeanor for camping on public property.

“They’re forcing someone under threat of arrest to pack up and move all their belongings,” said Niki Jones, executive director of the Sacramento Regional Coalition to End Homelessness. “And people’s bodies literally can’t handle the physical stress.”

‘Where do we go?’

While Newsom has provided an influx of money for shelter beds and other services in recent years — including $1 billion in this year’s budget for Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention funds that cities and counties can spend as they see fit — his recent executive order comes with no additional funding. Last year, California cities and counties reported having roughly 71,000 shelter beds. They’d need more than twice that to accommodate every homeless Californian.

“Folks are rightly asking, ‘Where do we go?’” Jones said.

Stephanie Ross, 49, has been homeless in Santa Cruz but receives help from local activists. Aug. 7, 2024. Photo by Manuel Orbegozo for CalMatters

Even when shelter beds are available, sweeps often fail to fill them. Santa Cruz, for example, estimates between 30 and 40 people were living in the park encampment it swept in April. Just 16 of those people accepted a shelter placement. No one kicked out of the nature preserve accepted shelter.

People living on the streets of Santa Cruz say police often tell them to go to a sanctioned encampment on the National Guard Armory property — where residents sleep in tents and get meals and showers. But many people won’t even consider it. Several unhoused people CalMatters spoke to said they didn’t want to live somewhere with strict rules and a curfew.

Stephanie Ross, who has been living on the streets of Santa Cruz for seven months, recently lost everything in a sweep. All she had left was the outfit she was wearing — a dinosaur-print dress, pants covered in pink flowers and a sweater she found on the ground. On Wednesday, she met up with McHenry to pick up a new tent to replace the one she says was confiscated by police a few days ago.

Ross said she can’t concentrate on finding a job or doing anything else, because she’s constantly worried about hiding her blankets and other possessions from the police. Even so, she worries she’d chafe under the rules of the Armory tent shelter.

“I need a little bit more freedom than that,” she said.

Demarr Clark, 42, said no one offered him a bed when police recently kicked him out of his camp on the sidewalk outside the Santa Cruz shelter. He lost everything he owned, including his tent, he said. Afterward, Clark moved across the street with a new tent gifted to him by a friend.

Clark grew up in Santa Cruz, and the city always seemed like a place where you could find somewhere out of the way to camp, he said. But that’s changing, he said. “It just seems like they have no tolerance for it anymore.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

Why Silicon Valley Wants to Kill This AI Bill

Khari Johnson / Monday, Aug. 12, 2024 @ 7:05 a.m. / Sacramento

Though lawmakers and advocates proposed dozens of bills to regulate artificial intelligence in California this year, none have attracted more disdain from big tech companies, startup founders, and investors than the Safe and Secure Innovation for Frontier Artificial Intelligence Models Act.

In letters to lawmakers, Meta said the legislation, Senate Bill 1047, will “deter AI innovation in California at a time where we should be promoting it,” while Google claimed the bill will make “California one of the world’s least favorable jurisdictions for AI development and deployment.” A letter signed by more than 130 startup founders and incubator Y Combinator goes even further, claiming that “vague language” could “kill California tech.”

Prominent AI researchers are also taking sides. Last week, Yoshua Bengio and former Google AI researcher Geoffrey Hinton, who are sometimes called the “godfathers of AI,” came out in support of the bill. Stanford professor and former Google Cloud chief AI scientist Fei-Fei Li, who is often called the “godmother of AI” came out against SB 1047.

The bill, approved 32-1 by the state Senate in May, must survive the Assembly Appropriations suspense file on Thursday and win final approval by Aug. 31 to reach Gov. Gavin Newsom this year.

The bill, introduced by San Francisco Democrat Scott Wiener in February, is sprawling. It would:

- Require developers of the most costly and powerful AI tools to test whether they can enable attacks on public infrastructure, highly damaging cyber attacks, or mass casualty events; or can help create chemical, biological, radioactive, or nuclear weapons.

- Establish CalCompute, a public “cloud” of shared computers that could be used to help build and host AI tools, to offer an alternative to the small handful of big tech companies offering cloud computing services, to conduct research into what the bill calls “the safe and secure deployment of large-scale artificial intelligence models,” and to foster the equitable development of technology.

- Protect whistleblowers at companies that are building advanced forms of AI and contractors to those companies.

The latter protections are among the reasons whistleblower and former OpenAI employee Daniel Kokotajlo supports SB 1047, he told CalMatters. He also likes that it takes steps toward more transparency and democratic governance around artificial intelligence, a technology he describes as “completely unregulated.”

Kokotajlo earlier this year quit his job as a governance researcher at OpenAI, the San Francisco-based company behind the popular ChatGPT tool. Shortly thereafter he went public with allegations that he witnessed a violation of internal safety protocols at the company. OpenAI was “recklessly racing” toward its stated goal of creating artificial intelligence that surpasses human intelligence, Koktajlo told the New York Times. Kokotajlo also believes that advanced AI could contribute to the extinction of humanity — and that employees developing that technology are in the best position to guard against this.

In June, Kokotajlo joined more than a dozen current and former employees of OpenAI and Google in calling for enhanced protections for AI whistleblowers. Those workers were not the first to do so; Google employees spoke out in 2021 after co-leads of the Ethical AI team were fired. That same year, Ifeyoma Ozoma, the author of a tech whistleblower handbook and a former Instagram employee, cosponsored California’s Silenced No More Act, a state law passed in 2022 to give workers the right to talk about discrimination and harassment even if they signed a non-disclosure agreement.

Kokotaljo said he believes that, had SB 1047 been in effect, it would have either prevented, or led an employee to promptly report, the safety violation he said he witnessed in 2022, involving an early deployment of an OpenAI model by Microsoft to a few thousand users in India without approval.

“I think that when push comes to shove, and a lot of money and power and reputation is on the line, things are moving very quickly with powerful new models,” he told CalMatters. “I don’t think the company should be trusted to follow their own procedures appropriately.”

When asked about Kokotajlo’s comments and OpenAI’s treatment of whistleblowers, OpenAI spokesperson Liz Bourgeois said company policy protects employees’ rights to raise issues.

Existing law primarily protects whistleblowers from retaliation in cases involving violation of state law, but SB 1047 would protect employees like Kokotajlo by giving them the right to report to the attorney general or labor commissioner any AI model that is capable of causing critical harm. The bill also prevents employers from blocking the disclosure of related information.

Whistleblower protections in SB 1047 were expanded following a recommendation by the Assembly Privacy and Consumer Protection committee in June. That recommendation came shortly after the letter from workers at Google and OpenAI, after OpenAI disbanded a safety and security committee, and after Vox reported that OpenAI forced people leaving the company to sign nondisparagement agreements or forfeit stock options worth up to millions of dollars. The protections address a concern from the letter that existing whistleblower protections are insufficient “because they focus on illegal activity, whereas many of the risks we are concerned about are not yet regulated.”

“Employees must be able to report dangerous practices without fear of retaliation.”

— Assemblymember Rebecca Bauer-Kahan, Democrat from San Ramon

OpenAI spokesperson Hannah Wong said the company removed nondisparagement terms affecting departing employees. Despite these changes, last month a group of former OpenAI employees urged the Securities and Exchange Commission to investigate nondisclosure agreements at the company as possible violations of an executive order signed by President Joe Biden last year to reduce risks posed by artificial intelligence.

Bay Area Democrat Rebecca Bauer-Kahan, who leads the Assembly Privacy and Consumer Protection Committee, said she helped add the whistleblower protections to SB 1047 because industry insiders have reported feeling muzzled by punitive non-disclosure agreements, even as more of them speak out about problems with AI.

“If Californians are going to feel comfortable engaging with these novel technologies, employees must be able to report dangerous practices without fear of retaliation,” she said in a written statement. “The protections the government provides should not be limited to the known risks of advanced AI, as these systems may be capable of causing harms that we cannot yet predict.”

Industry says bill imperils open source, startups

As vocal as they’ve been in opposing SB 1047, tech giants have said little about the bill’s whistleblower protections, including in lengthy letters that Meta, Microsoft, and Google sent to lawmakers. Google declined to comment about those provisions, while Meta declined to make California public policy lead Kevin McKinley available for comment. OpenAI pointed to a previous comment by Bourgeois that stated, “We believe rigorous debate about this technology is essential. OpenAI’s whistleblower policy protects employees’ rights to raise issues, including to any national, federal, state, or local government agency.”

Instead, opponents have highlighted the bill’s AI testing requirements and other safety provisions, saying compliance costs could kneecap startups and other small businesses. This would hurt the state economy, they add, since California is a center of the AI industry. The bill, however, limits its AI restrictions to systems that cost more than $100 million, or require more than a certain quantity of computing power to train. Supporters say the vast majority of startups won’t be covered by the bill.

Opponents counter that small businesses would still suffer because SB 1047 would have a chilling effect on individuals and groups that release AI models and tools free to the public as open source software. Such software is widely used by startups, holding down costs and providing them a basis on which to build new tools. Meta has argued that developers of AI software will be less likely to release it as open source out of fear they will be held responsible for all the ways their code might be used by others.

“If we over regulate, if we over indulge and chase a shiny object, we can put ourselves in a perilous position.”

— Gov. Gavin Newsom

Open source software has a long history in California and has played a central role in the development of AI. In 2018, Google released as open source its influential “BERT,” an AI model that laid the groundwork for large language models such as the one behind ChatGPT and that sparked an AI arms race between companies including Google, Microsoft, and Nvidia. Other open source software tools have also played important roles in the spread of AI, including Apache Spark, which helps distribute computing tasks across multiple machines, and Google’s TensorFlow and Meta’s PyTorch, both of which allow developers to incorporate machine learning techniques into their software.

Meta has gone farther than its competitors in releasing the source code to its own large language model, Llama, which has been downloaded more than 300 million times. In a letter sent to Wiener in June, Meta deputy chief privacy officer Rob Sherman argued that the bill would “deter AI innovation in California at a time when we should be promoting it” and discourage release of open source models like Llama.

Ion Stoica is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley and cofounder of Databricks, an AI company built on Apache Spark. If SB 1047 passes, he predicts that within a year open source models from overseas, likely China, will overtake those made in the United States. Three of the top six top open source models available today come from China, according to the Chatbot Arena evaluation method Stoica helped devise.

Open source defenders also voiced opposition to SB 1047 at a town hall hosted with Wiener at GitHub, an open source repository owned by Microsoft, and a generative AI symposium held in May.

Newsom, who has not taken a position on the legislation, told the audience it’s important to respond to AI inventors like Geoffrey Hinton who insist on the need for regulation , but also said he wants California to remain an AI leader and advised lawmakers against overreach. “If we over regulate, if we over indulge and chase a shiny object, we can put ourselves in a perilous position,” the governor said. “At the same time we have an obligation to lead.”

Aiming to protect tech workers and society

Sunny Gandhi, vice president of government affairs at Encode Justice, a nonprofit focused on bringing young people into the fight against AI harms and a cosponsor of the bill, said it has sparked a backlash because tech firms are not used to being held responsible for the effects of their products

“It’s very different and terrifying for them that they are now being held to the same standards that pretty much all other products are in America,” Ghandi said.” There are liability provisions in there, and liability is alien to tech. That’s what they’re worried about.”

Wiener has disputed some criticisms of his bill, including a claim, in a letter circulated by startup incubator Y Combinator and signed by more than 130 startup founders, that the legislation could end up sending software developers “to jail simply for failing to anticipate misuse of their software.” That assertion arose from the fact that the bill requires builders of sufficiently large language models to submit their test results to the state and makes them guilty of perjury if they lie about the design or testing of an AI model.

“It’s very different and terrifying for them that they are now being held to the same standards that pretty much all other products are in America.”

— Sunny Gandhi, vice president of government affairs at Encode Justice

Wiener said his office started listening to members of the tech community last fall before the bill was introduced and made a number of amendments to ensure the law only applies to major AI labs. Now is the time to act, he told startup founders, “because I don’t have any confidence the federal government is going to act” to regulate AI.

Within the past year, major AI labs signed on to testing and safety commitments with the White House and at international gatherings in the United Kingdom, Germany, and South Korea, but those agreements are voluntary. President Biden has called on Congress to regulate artificial intelligence but it has yet to do so.

Wiener also said the bill is important because the Republican Party vowed, in the platform it adopted last month, to repeal Biden’s executive order, arguing that the order stifles innovation.

In legislative hearings, Wiener has said it’s important to require compliance because “we don’t know who will run these companies in a year or five years and what kind of profit pressures those companies will face at that time.”

AI company Anthropic, which is based in San Francisco, came out in support of the bill if a number of amendments are made, including doing away with a government entity called the Frontier Models Division. That division, which would review certifications from developers, establish an accreditation process for those who audit AI, and issue guidance on how to limit harms from advanced AI. Wiener told the Y Combinator audience he’d be open to doing away with the division.

Kokotajlo, the whistleblower, calls SB 1047 both a step in the right direction and not enough to prevent the potential harms of AI. He and the other signatories of the June letter have called on companies that are developing AI to create their own processes whereby current and former employees could anonymously report concerns to independent organizations with the expertise to verify whether concern is called for or not.

“Sometimes the people who are worried will turn out to be wrong, and sometimes, I think the people who are worried will turn out to be right,” he said.

In remarks at Y Combinator last month, Wiener thanked members of open source and AI communities for sharing critiques of the bill that led to amendments, but he also urged people to remember what happened when California passed privacy law in 2018 following years of inaction by the federal government.

“A lot of folks in the tech world were opposed to that bill and told us that everyone was going to leave California if we passed it. We passed it. That did not happen, and we set a standard that I think was a really powerful one.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

OBITUARY: John William McKeown, 1946-2024

LoCO Staff / Monday, Aug. 12, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

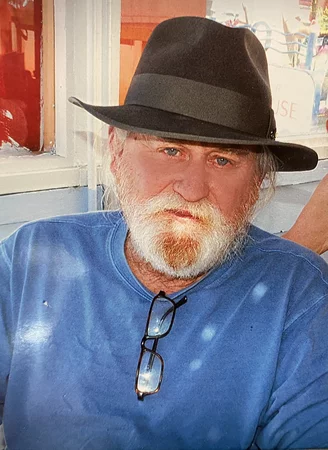

With great sadness, we announce that John William McKeown, aka Papa John, passed

away suddenly on May 23, 2024, at the age of 77. John was born August 19, 1946, in

Pawtucket, Rhode Island to Frances and John McKeown.

For the past fifty years his home has been in Bayside. He was a master welder and fabricator. He could build anything. He could drive anything. He was the man with the plan. John lived and loved life with passion. He possessed a sharp intellect, a righteous sense of justice, a warrior’s courage, and a clever sense of humor. He was a beloved patriarch; life partner, dad, granddad and great-grandad; he was a dearly loved brother, uncle, great-uncle, and best friend. John established deep relationships and earned the trust, respect, and admiration of many who would call him brother, and many others who would think of him as dad. He valued his family and friends over all else.

This extraordinary man was a legend in his own lifetime! He will be dearly missed.

His family will host a celebration of life on August 18, 2024, starting at 2 p.m. at the Bayside Grange.

“For small creatures such as we, the vastness is bearable only through love.” Carl Sagan.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of John McKeown’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

(UPDATE: EVACUATION ORDER EXPANDED) Boise Fire Near Orleans Explodes to 915 Acres With 0% Containment; Evacuation Order in Effect

Isabella Vanderheiden / Saturday, Aug. 10, 2024 @ 9:22 a.m. / Fire

###

UPDATE 4:30 p.m: Earlier this afternoon the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office issued a notice expanding the evacuation order for communities surrounding the Boise Fire. Residents in HUM-E009-A, HUM-E009-B and HUM-E025-B should evacuate immediately.

An evacuation warning is currently in place for HUM-E009-E, HUM-E009-D, HUM- E025-A and HUM-E025-E.

“Residents should be ready to evacuate at a moment’s notice if fire behavior and weather conditions worsen,” according to the Sheriff’s Office. “Residents are advised to prepare for potential evacuations, including gathering personal supplies and securing overnight accommodations.”

A temporary evacuation point has been established at the Karuk Department of Natural Resources at 39051 State Route 96 in Orleans.

Additional evacuation information can be found on the Sheriff’s Office Facebook page. A map of current evacuation orders and warnings can be found here.

###

Original post:

Press release from Six RiversNational Forest:

Orleans, CA., August 10, 2024— The Boise Fire, located approximately 5 miles southeast of Orleans in the Boise Creek Drainage, is experiencing active fire behavior with rapid rate of spread. The fire is currently 915 acres and 0% contained. Fire behavior includes crowning, uphill runs, and long-range spotting. Multiple structures are threatened. Several ground and aerial resources are on scene utilizing an aggressive, direct and full suppression strategy.

A Complex Incident Management Team was ordered. California Interagency Incident Management Team 10 will in-brief at 6pm today, August 10.

Evacuations

Evacuation order and warnings are in effect. For current updates on evacuations, visit the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office Facebook page or the county’s website.

Conditions are subject to change at any time, visit Genasys for a full zone description. Sign up for Humboldt Alert emergency notifications at the county’s website.

Fire Restrictions

Forest fire restrictions also went into effect on July 12th. Campfires and stove fires are restricted to those developed areas listed in the forest order located at the Six Rivers National Forest’s website. Smoking, welding, and operating an internal combustion engine also have restrictions in place.

Forest Closures

There are currently no forest closures in effect at this time. Conditions are subject to change at anytime for updated forest closure information visit https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/srnf/notices/?cid=FSEPRD1096395

Michael E. Spagna to Serve as Acting President of Cal Poly Humboldt

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Aug. 10, 2024 @ 9:01 a.m. / Cal Poly Humboldt

Meet your new interim president, folks! | Photo: California State University

###

PREVIOUSLY: Cal Poly Humboldt President Tom Jackson, Jr. to ‘Step Away’ Next Month But Remain at University

###

Press release from California State University:

California State University (CSU) Chancellor Mildred García has appointed CSU Dominguez Hills provost and vice president for Academic Affairs Michael E. Spagna as acting president of California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt effective August 26, 2024. At its September meeting, the CSU Board of Trustees will be asked to approve Spagna as interim president for approximately 12 months while the board conducts a national search for the university’s next regularly appointed president.

“I want to thank Chancellor García for the opportunity to serve Cal Poly Humboldt,” said Spagna. “I’m excited by the prospect of working collaboratively with the university’s dedicated faculty and staff and the greater North Coast community to continue advancing Cal Poly Humboldt’s vision as a center for interdisciplinary study that prepares students seeking to make a difference in our world.”

Spagna succeeds President Tom Jackson Jr., who in July announced his decision to step down and transition to a faculty role.

“Dr. Spagna has personified the mission and core values of the CSU for more than three decades,” said Chancellor García. “He is an extraordinarily skilled and innovative educational leader with a demonstrated and unwavering commitment to improving access, retention and success for diverse students through the deployment of data-informed practices. In addition, he has a remarkable ability to cultivate collaboration across university operations and to inspire external partnerships and support. Dr. Spagna is the ideal leader to guide Cal Poly Humboldt through this time of transition.”

As provost and vice president for Academic Affairs at CSU Dominguez Hills since 2017, Spagna has provided strategic leadership and oversight for the university’s academic vision. He also serves at the system level as provost representative on the CSU Admission Advisory Council and as commissioner for the CSU Commission of Professional and Continuing Education (CPaCE).

Prior to joining CSUDH, Spagna held several positions at California State University, Northridge (CSUN) over a 25-year period, including professor and dean of the Michael D. Eisner College of Education, where he cultivated a $7 million gift to the university’s Center for Teaching and Learning.

From 2008 to 2023, Spagna also served as chair of the L.A. Compact’s Institutions of Higher Education (IHE) Collaborative, where he led a consortium workgroup dedicated to improving educational and career outcomes for the youth of Los Angeles.

Prior to his service at CSUN, Spagna served as consultant to the California State Department of Education; coordinator of the Services to Students with Learning Disabilities program at University of California, Berkeley; learning disabilities specialist and lecturer at Chabot College in Livermore, California; and special education teacher at Landmark West School in Culver City, and at the Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital at UCLA.

Spagna is a scholar in educator preparation and special education. He received a Ph.D. in special education from the UC Berkeley and San Francisco State University joint doctoral program. He earned a master’s in special education from UCLA and a bachelor’s in communicative disorders from Northwestern University.

They’re Gonna Torch a Building on Tompkins Hill Road Sunday Morning So’s to Train Up New Eel River Valley Firefighters

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Aug. 10, 2024 @ 8 a.m. / Non-Emergencies

Fire’s gonna be right about here, more or less.

Press release from Fortuna Fire:

The Eel River Valley Probationary Fire Academy will conduct a structure fire training burn on August 11, 2024, on Tompkins Hill Road in Fortuna. The training will begin at 8:00 a.m. with multiple interior firefighting evolutions followed by demolition of the structure by approximately 2:00 p.m. Access to Tompkins Hill Road may be subject to short delays to allow for water tender/shuttle operations. Caution is advised.

Through the generosity of the property owners and the cooperation of the North Coast Unified Air Quality Management District, these new firefighters from in and around the Eel River Valley will experience the opportunity to test the various skills learned in the academy. One of the primary objectives of the training will be to provide students the opportunity to experience live fire in a controlled environment, allowing the students to feel the reality of heat as in that of an actual structure fire. Training of this type is invaluable and not easy to come by as structures available for training are few and far between.

The live fire training will wrap up an intense seven-week academy where recruits were taught entry-level structural firefighting and rescue skills necessary to bring these new firefighters into compliance with National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) training standards and ensure that they can operate both safely and efficiently on the fire ground and/or rescue scene.

Please forward any questions to Public Information Officer Kirsten Foley, Fortuna Volunteer Fire Department. (707)407-6516.