If You Have Strong Feelings About Julia Morgan’s ‘Federation Hearthstone,’ a Four-Sided Fireplace in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, You’re Going to Want to Get Your Ass to Sacramento Next Week

LoCO Staff / Friday, April 26, 2024 @ 10:37 a.m. / History

Photo: Stacey De Shazo, via California State Parks.

Or, actually, you can just join the Zoom too, looks like. Either way.

Press release from the California Department of Parks and Recreation:

The State Historical Resources Commission (Commission) will meet in Sacramento on Friday, May 3, at 9 a.m. and will consider nine properties recommended for placement on the National Register of Historic Places. Properties nominated include the Bell Canyon Equestrian Center and Scarlett Ranch, both in Ventura County, a four-faced fireplace designed by famed architect Julia Morgan located in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, and a Craftsman style clubhouse designed for the Petaluma Woman’s Club by architect Brainerd Jones. The Commission will forward properties nominated to the National Park Service for final consideration by the Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places.

WHAT: State Historical Resources Commission Meeting

WHEN: Friday, May 3 at 9 a.m.

WHERE: California Natural Resources Agency Auditorium, 715 P Street, Sacramento, CA 95814.

WHO: State Historical Resources Commissioners, Office of Historic Preservation staff, and members of the public.ADDITIONAL DETAILS: The full agenda and information for attending the meeting in person or joining virtually through Cal-Span or Zoom is available at parks.ca.gov/PublicNotices. For more information about the Commission and the Office of Historic Preservation, visit ohp.parks.ca.gov.

California State Parks supports equal access. If you are in need of a reasonable modification or special accommodation for the meeting or in accessing the agendas or submitting comments, please contact the Office of Historic Preservation at (916) 445-7000 or email calshpo.shrc@parks.ca.gov.

BOOKED

Yesterday: 8 felonies, 6 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Jan. 2

CHP REPORTS

Us101 S / Herrick Ave Onr (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Sr36 / Alderpoint Rd (HM office): Traffic Hazard

1050 Mm96 W Hum R10.50 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Driver Trapped After Seizure Reportedly Leads to Crash at Fourth and I Streets in Eureka

Mad River Union: APD: Arcata declares State of Emergency

Cal Poly Humboldt Responds to Protesters’ Demands, Explaining Investments and Principles While Promising Consequences For Those Who Break the Law

Ryan Burns / Friday, April 26, 2024 @ 10:27 a.m. / Activism , Cal Poly Humboldt

Photo by Ryan Burns.

###

Shortly after 10 o’clock this morning, Cal Poly Humboldt posted the following response to demands from the protesters who have been demonstrating on campus and occupying Siemens Hall in support of Palestinian liberation:

The following was shared yesterday during a conversation with student protestors.

This is an initial response intending to make a good faith effort to respond, and is meant to lead to additional dialogue.

###

The Cal Poly Humboldt pro-Palestine protests have elevated a remarkable number of important questions, opened a space for difficult, meaningful conversations, and also raised concerns about what principles of the community we bring into spaces of disagreement. Even in the midst of this challenging period for our community, we remain firmly rooted in our University’s purpose: to provide the highest quality and affordable college education built on the contributions of diverse students, staff, and faculty who are committed to a just and sustainable world.

We write today in this spirit, while also reasserting our responsibility for civil discourse and fact-based debate. In particular, we would like to provide context and feedback to the stated demands of the protesters. They have asked the campus to:

1. Disclose all holdings and collaborations with Israel.

It is important to highlight that Cal Poly Humboldt is among the higher education leaders in environmentally and socially responsible investing. In 2014, with extensive student involvement, an investment strategy focused on reducing investments in the fossil fuel industry and in tracking investments in socially concerning sectors was adopted. Last year, again with student involvement and assistance, a new policy focused on Environmentally & Socially Responsible (ESR) investing was adopted. This policy takes a “positive investment” approach to select funds with strong environmental, social, and governance practices, and again puts Humboldt at the leading edge of responsible investing within higher education.

The investments in the University’s endowment does not include any direct investment in defense companies or any securities issued by Israeli companies or organizations, or to defense firms. In fact, because of the relatively small size of the endowment, the investment strategy does not include direct investment in any specific companies or securities. Instead, the portion of the investment in securities is in mutual funds, which are bundles of many securities that reflect the portfolios of numerous different investment managers.

So any holdings of the securities in question would represent indirect investment. Our estimates put the potential indirect investment in the areas that are asked about at less than 1% of the investment portfolio of more than $51 million. Of this, our estimate of potential defense investment is less than 0.5% of the entire portfolio, though that can fluctuate over time. This estimate is probably high as these companies do not produce weaponry but rather components of various industrial products (like wind turbines and aviation parts). The portion of the indirect investment in Israeli companies or organizations is likewise less than 0.5%, and can fluctuate over time. These securities, which again are bundled in different mutual funds, are software companies and banks, and there is also less than 0.1% in bonds. Any of these holdings could be sold by the fund manager at any time.

We would welcome the opportunity to discuss the investment policies in the future.

2. Cut all ties with Israeli universities.

Cal Poly Humboldt has a commitment to global engagement. While we have no current ties with Israeli Universities, we are open to connecting with universities across the world in an effort to build connections and expand understanding. The Cal Poly Humboldt catalog listing for a study abroad program with the University of Haifa in Haifa, Israel is a California State University International Study Abroad (CSU IP) program, not a Cal Poly Humboldt program. The CSU IP Haifa program is not currently enrolling students. Current Bilateral Exchange Programs with Cal Poly Humboldt are listed online.

Information about agreements with other universities is also available on campus websites or with an email to the Dean of Extended Education & Global Engagement. We encourage our students to speak and engage with faculty as well as campus administrators. Our doors are always open to our students.

3. Divest from companies and corporations complicit in the occupation of Palestine:

Please see the investment information in #1. We do not have a way of measuring the specific language included in this request.

4. Drop charges against and halt the harassment of student organizers by law enforcement.

University policy and conduct violations will follow established procedures, and there will be consequences for actions that violate policy or law. However, students who elect to evacuate the building and support efforts to clear the building will have their actions considered as a mitigating factor within those processes.

5. University to publicly call for a ceasefire and end to the occupation of Palestine.

Cal Poly Humboldt is committed to social justice and the Graduation Pledge to guide everyone’s social and environmental consequences of their decisions. We are supportive of a peaceful and just world which affords the opportunity for all human beings to flourish and achieve their potential.

6. “We want the university to either amend or remove the time, manner or place clause [of its free expression policy] which allows them to call the police on students for organizing in ways that they deem inappropriate.” (Link)

The University’s Time, Place and Manner (TPM) policy exists to protect the rights of the entire campus community to a secure environment that is conducive to the pursuit of knowledge, freedom of inquiry, freedom of speech and freedom of assembly. The policy is content-neutral in its approach to speech and assembly, protecting our freedoms while also ensuring that the rights of the rest of the campus community to a safe and secure environment are protected. Part of protecting our rights is protecting the health and safety of persons, and the security of property, for which uniformed police officers may be required.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- (VIDEO) DAY FOUR: Occupy Cal Poly Humboldt Protester Details Group’s Demands, Motivations and Views on President Tom Jackson, Law Enforcement and Their Campus Impact

- BREAKING: Cal Poly Humboldt Faculty Pass Vote of No Confidence in President Tom Jackson Amid Ongoing Student Protest

- DAY THREE: (PHOTOS) Student Protesters List Demands, Expand Graffiti Messaging and Voice Camaraderie on Third Day of Cal Poly Humboldt Campus Occupation

- Cal Poly Humboldt Says Campus Will be Closed Through at Least the Weekend Due to Ongoing Pro-Palestine Protests

- DAY TWO: The Morning After Cops Clash With Student Protesters, CPH Campus is Closed, Occupied Building Barricaded

- Legendary Rebellious Rapper Chuck D’s Cal Poly Humboldt Event Canceled By In-Progress, On-Campus Rebellion

- DAY ONE: Major Pro-Palestine Protests at Cal Poly Humboldt Provoke Massive Police Response; Protesters Occupy Siemens Hall; Reports of Violent Force Between Activists and Law Enforcement

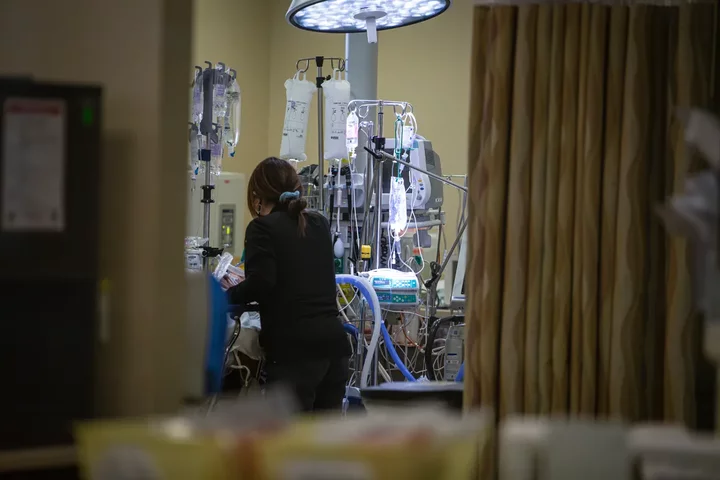

A New California Rule Tries to Hold Down Your Health Care Costs. Here’s How It Works

Kristen Hwang / Friday, April 26, 2024 @ 7:40 a.m. / Sacramento

You won’t notice it right away, but a new California state agency took a major step this week toward reining in the seemingly uncontrollable costs of health care.

The Office of Health Care Affordability approved the state’s first cap on health industry spending increases, limiting growth to 3% by 2029. This means that hospitals, doctors and health insurers will need to find ways to cut costs to prevent annual per capita spending from exceeding the target. Between 2015 and 2020, per capita health spending in California grew more than 5% each year, according to federal data.

A board appointed by Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature on Wednesday approved the new regulations in a 6-1 vote.

Health and Human Secretary Dr. Mark Ghaly, who chairs the board, said the regulations recognize that Californians are struggling every day to pay for health care and the state has a role in helping them.

“We have a place in making sure it becomes more affordable,” Ghaly said.

Hospitals, doctors and insurers battled over the regulations for months, arguing that rising inflation and labor costs would make the target impossible to achieve. An earlier proposal would have moved more aggressively to cap costs. The final version gives the industry time to rein in spending.

Ghaly said he is confident health care industry leaders will be able to find solutions to meet the new target. “When that happens, it’s going to be great for Californians.”

How does it work?

Increased health spending most often translates to higher out-of-pocket costs for consumers in the form of premiums, deductibles and copays. The annual spending benchmark would require health care providers to limit spending growth to 3.5% next year, decreasing to 3% by 2029. Providers — including hospitals, doctors groups and health insurers — will have to submit spending data to the state to demonstrate that they are complying with the cap.

The affordability office also has authority to enforce penalties, including performance improvement plans and fines, for organizations that exceed the benchmark. It will not enforce penalties until 2029.

Assemblymember Jim Wood, a Democrat from Ukiah, at the meeting urged the board to send a clear message to Californians that the state is taking affordability seriously. Wood spearheaded the legislation that created the office in 2022.

“It is not an exaggeration to say that people are deciding whether to get food on the table or get their medicines,” Wood said. “This is not an exercise. This is an effort to impact the real life experiences of people in California.”

How will providers lower health care costs?

Ultimately, it’s up to the health care organizations.

The board hopes health care organizations will crack down on inefficient and wasteful health spending, such as administrative inefficiency and redundant or poorly coordinated testing. But it doesn’t want to discourage spending on primary care and behavioral health. The affordability office will monitor spending in those areas to ensure organizations do not reduce services or access to preventative care.

Will Californians see cheaper health care?

Yes, but it may not feel like it.

The growth cap is not a mandate for providers to lower prices. Californians will not pay less for health insurance next year than they did this year. For those who already can’t afford health care — some estimates peg that number at more than 50% of Californians — the cap won’t bring any immediate relief.

The goal of the cap is to prevent future prices from increasing uncontrollably. This year, health insurance premiums on the state’s Affordable Care Act Exchange increased an average of 9.6% statewide with double-digit increases in many regions. Personal health care spending shot up 60% between 2010 and 2020, reaching $405 billion, according to federal data. That’s $10,299 per person. Household health spending has also grown twice as fast as wages, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In an effort to recognize how many Californians can’t pay for health care, the affordability office tied the cap to the average annual median household income growth, which has historically been about 3% over the past two decades.

Will California succeed?

California is not the first state to try to bring health care costs down. Eight other states have similar cost benchmarks, although California’s is one of the more aggressive targets.

Massachusetts, the first state to set a health spending benchmark, has largely met its target growth rate of 3.6% over the past 10 years.

In recent years however, with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, states have found it harder to contain costs. Connecticut, Delaware and Massachusetts significantly surpassed their spending targets between 2020 and 2021 primarily because of increased health care use, according to a report by the policy journal Health Affairs.

Who opposed the spending cap?

Former state Sen. Dr. Richard Pan was the sole no vote on the new regulations, arguing that the state needed to recognize how changing population needs like aging would affect future health care spending.

Pan and groups representing hospitals and doctors have argued that the state should have set a more “realistic” target rather than one most organizations will fail to achieve.

In a letter to the board, the California Hospital Association proposed a 6.3% target for 2025 and urged state regulators to consider how inflation, aging and a new law that raises the state minimum wage for health care workers would drive up costs. Association President Carmela Coyle said in a statement after the vote that the new regulations will worsen access to care as organizations are forced to make cuts.

“The office is charged by law to do more than limit spending,” Coyle said. “It’s imperative that the board analyze the impact of its decision on patients and create a process to reconsider future targets to protect access to equitable, quality care for every Californian.”

The California Association of Health Plans, representing most insurers, and the California Medical Association, which represents doctors, each voiced support for the phased-in 3% target this week but have previously pushed the affordability office to consider other options.

“Adopting a 3% health care spending growth target, which most physician practices and health care entities will be unable to meet, will negatively impact access to health care for Californians,” medical association President Dr. Tanya Spirtos wrote ahead of the vote.

Who supported the health spending cap?

The new regulations are largely supported by unions, employers and consumer advocates. Supporters turned up in force at the vote to give examples of how housekeepers, bartenders, teachers, carpenters, nurses and other workers cannot afford health care even with insurance and frequently forgo raises to pay for ever-growing medical spending.

Learn more about legislators mentioned in this story.

“Consumers, particularly people of color, are burdened by record medical debt and are making daily choices between health care, housing, and food,” said Kiran Savage-Sangwan, executive director of the California Pan-Ethnic Health Network, at the meeting. “If we want a different outcome, we need to change the incentives in our system.”

Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access California, said the new spending target was “long-awaited, but welcome news for Californians.”

“California consumers, patients and payers have been screaming for years about the cost,” Wright said. “This will provide some downward pressure on what has been ever-increasing hikes in our health care costs.”

###

Supported by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF), which works to ensure that people have access to the care they need, when they need it, at a price they can afford. Visit www.chcf.org to learn more.

The Calmatters Ideas Festival takes place June 5-6! Find out more and get your tickets at this link.

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

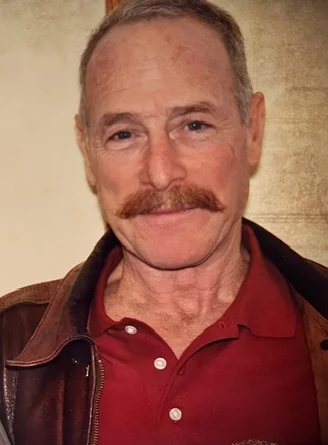

OBITUARY: George ‘Jim’ Habib, 1945-2024

LoCO Staff / Friday, April 26, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

On February 2, 2024 George “Jim” Habib passed away peacefully surrounded by his loving

family and closest friends.

Born on June 22, 1945 in Oxnard, Jim quickly developed a reputation for his penchant to conquer the unknown and to be involved in all things adventure. As a young man, he was often found fixing up old cars, sailing around Catalina Island or hitchhiking his way across the U.S and many parts of Europe. A devoted duty to his country, Jim enlisted in the Marine Corp in July of 1966 and shortly after, was deployed to Vietnam with Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 13 as an aircraft maintainer in Chu Lai.

Propelled for exploration, Jim moved to Humboldt County where he met his beloved wife of 48 years, Gloria Wood (nicknamed Jake), who was also searching for an untethered, fulfilling life many parts of the rugged North Coast of California offered. Establishing a budding life together, Jim was drawn to the ocean and began fishing in 1972 on the F/V Jumping Jack. Those that know Jim well, would not be surprised as he quickly became the skipper of his own boat, named the Shirttail until 1976, and then the legendary Challenger from 1977-2008. After many successful seasons, as well as some breathtaking moments, he was always known to be one of the first to go out and the last one to come back, earning his nickname, “White Water Jim”.

In 2008, a major winter storm tested Jim’s fortitude once again as the Challenger was ripped from its moorings and subsequently beached and ultimately destroyed. Later, he was quoted in the Times-Standard for saying, ”It was still upright, wallowing around, but it was done.” Despite this tragedy, Jim forged ahead by building his prized fishing vessel, aptly named the Defender. Still to this day, Jim’s influence can be felt throughout Humboldt’s tight-knit fishing community and echoed on the original Trinidad pier.

Jim’s passionate curiosity and innate nature to reveal the wonders of the world to those he held dearest, are reflected in his daughters and granddaughter’s willingness to capture life to the fullest. He will always be remembered for lending a hand to those in need, from towing wayward fishermen back to harbor, to being a steady hero in his daughter’s lives. He was always ready and willing in the moments that mattered no matter how big or small.

Jim’s legacy will be his kind heart, honest nature, pride in workmanship, and his unconditional love for his daughters, granddaughters, and beloved wife.

Jim is survived by his wife of 48 years, Gloria “Jake” Habib, daughters Corinna Mosher (Habib) and JoAnna Pifferini (Habib), granddaughters Cleo Pifferini and Josie Pifferini, sons in-law Tim Mosher and Travis Pifferini, sister Linda Liker, nieces Amy Moore, Heidi Barrett and nephew Karl Lepper.A celebration will be held July 13 at 1 p.m. at the Trinidad Town Hall after the scattering of Jim’s ashes at sea. This will be a time for family and friends to honor, share stories and celebrate the legend of Jim Habib.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Jim Habib’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

OBITUARY: Bonnie Jean Fyle, 1950-2024

LoCO Staff / Friday, April 26, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

On April 17, 2024, our beloved mother, grandmother and sister, Bonnie Jean Fyle, sadly passed away due to stage 4 COPD.

Bonnie was born on Sept. 26, 1950 in Duluth, Minn. to Geraldine and Wallace Walgren. She attended Hermantown High School in Duluth and after spending the majority of her younger years in this town, she decided to begin a new journey and moved to California with her two children, Kelly and Bryon Fyle. In 1980, little Kimberlee Fyle was born. Bonnie truly loved and admired her mother Geri Jones, and always felt she needed to be close to her. After spending nearly a decade in the Bay Area, she relocated to the small town of Mad River (population of 35, at the time). Away from the chaotic urban lifestyle, to an area surrounded by the beauty and serenity of nature, is where she decided to raise her three children.

Anyone who knew Bonnie knew she believed in God and that she was a lifetime Minnesota Vikings fan. Some would say she was the 12th player for this team! Furthermore, she was also blessed enough to live through the many eras of music and witnessed its evolution, enjoying the sounds of great artists such as The Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, Lynyrd Skynyrd and many more great albums. She enjoyed all novels and movies created by Stephen King. She also enjoyed playing Yahtzee and watching game shows. Bonnie was a funny, beautiful woman with a heart of gold. The things she didn’t like: The Green Bay Packers and frogs.

Bonnie Jean Fyle is survived by her three children: Kelly Heiser, Bryon Fyle and Kimberlee Fyle, along with her grandchildren Cody Turner, Alexis Heiser, Trinity Fyle as well as her two great-grandkids, Ariana and Lincoln Turner. In addition, she is survived by her siblings: Wally Walgren, Steve Walgren, Wana Jones, Donna Jones and Joe Jones. She will be missed.

Join us for her celebration of life ceremony on Saturday, June 8, 2024 at 1 p.m. at the Mad River Burger Bar.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Bonnie Fyle’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

(VIDEO) DAY FOUR: Occupy Cal Poly Humboldt Protester Details Group’s Demands, Motivations and Views on President Tom Jackson, Law Enforcement and Their Campus Impact

Andrew Goff / Thursday, April 25, 2024 @ 5 p.m. / Activism , Cal Poly Humboldt

A light drizzle dampened protesters’ tents, signs and chalk messages as the Occupy Cal Poly Humboldt demonstration entered its fourth day. The campus remains officially closed and will be so through the weekend as pro-Palestinian protesters continue their sit-in of Siemens Hall and public spaces around its perimeter.

The Outpost returned to CPH’s campus Thursday and, for the first time since the start of the protest, we were granted an on-camera interview with one of the involved students. In the clip above, occupier Jackie discusses the state of the demonstration, the CPH administration’s accusations of theft and vandalism, and the occupation’s impacts on other students (among other topics).

PREVIOUSLY:

- Cal Poly Humboldt Faculty Pass Vote of No Confidence in President Tom Jackson Amid Ongoing Student Protest

- DAY THREE: (PHOTOS) Student Protesters List Demands, Expand Graffiti Messaging and Voice Camaraderie on Third Day of Cal Poly Humboldt Campus Occupation

- Cal Poly Humboldt Says Campus Will be Closed Through at Least the Weekend Due to Ongoing Pro-Palestine Protests

- DAY TWO: The Morning After Cops Clash With Student Protesters, CPH Campus is Closed, Occupied Building Barricaded

- Legendary Rebellious Rapper Chuck D’s Cal Poly Humboldt Event Canceled By In-Progress, On-Campus Rebellion

- DAY ONE: Major Pro-Palestine Protests at Cal Poly Humboldt Provoke Massive Police Response; Protesters Occupy Siemens Hall; Reports of Violent Force Between Activists and Law Enforcement

Sheriff’s Office Issues Statement on Today’s Shootings in Cutten

LoCO Staff / Thursday, April 25, 2024 @ 4:09 p.m. / Crime

PREVIOUSLY:

###

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

On April 25, 2024, at approximately 10:31 a.m., the Sheriff’s Office Emergency Communications Center received a 911 call reporting a person had been shot in the 2400 block of Fern Street, Eureka. Deputies were immediately dispatched to the area. While deputies were enroute, it was learned that a White Male Adult walked up to a 75-year-old woman who was standing in front of her garage with her sister and shot at her multiple times. The woman was struck by gunfire, and the suspect fled on foot westbound on Fern toward Walnut Avenue.

Deputies arrived on the scene at approximately 10:38 a.m. and saw a subject matching the description of the suspect walking on Fern. Two deputies exited the patrol vehicle and contacted the suspect at gunpoint. The suspect refused commands and fled into a residence across the street from the location where the victim was shot. An additional deputy arrived on the scene, and the three deputies surrounded the residence while additional units responded to the scene. At approximately 10:40 a.m., the suspect exited the residence and walked toward the deputies’ location, pointing a firearm in the direction of the deputies. The suspect refused commands, and one deputy shot the suspect. The suspect dropped the firearm and fell to the ground. Deputies secured the suspect in handcuffs, and emergency medical assistance was called to the scene. A hasty search was conducted inside the residence to ensure there were no other victims or suspects inside. The deputies then rendered medical aid to the suspect by packing his wounds and performing CPR. Paramedics arrived on the scene and took over the medical care of the suspect and the 75-year-old female victim. Both were subsequently transported to an area hospital where they are receiving treatment for their injuries.

The County Critical Incident Response Team (CIRT) protocol was implemented to investigate the shooting. The Humboldt County District Attorney and the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office are leading the investigation with other county law enforcement investigators. After CIRT investigators collect all the evidence and conduct all the interviews, more information will be release regarding this incident.

This case is still under investigation.

Anyone with information about this case or related criminal activity is encouraged to call the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office at (707) 445-7251 or the Sheriff’s Office Crime Tip line at (707) 268-2539.