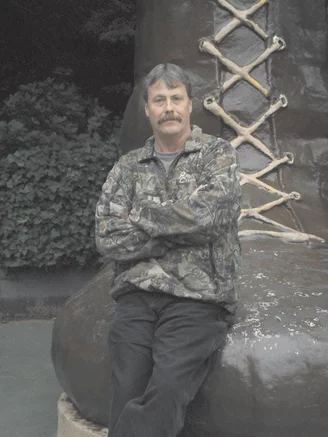

OBITUARY: Mark Robert Maillie, 1964-2023

LoCO Staff / Friday, July 7, 2023 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Mark Robert Maillie was born on April 5, 1964 to Robert Maillie and Jessie Desadier

in Roseburg, Oregon. His family later moved to Eureka, where Mark would grow up

and meet the love of his life, Shirley. They were married on September 28, 1985.

Mark and Shirley would go on to welcome three children, Max, Rex, and Lindsey. Anyone who knew Mark knew that cancer was present in his life from 2006 on. During this first diagnosis of large B cell Lymphoma, he was told that the survival rate was low. He underwent treatment despite this statistic. In late 2006 the oncologist said he would do one more treatment so he would get one more Christmas with his family. Little did everyone know this treatment was a miracle and put him in remission. From then on he lived with a new sense of gratefulness.

Although cancer is a part of his story, it’s not his whole story. Mark had worked at Pacific Clears 19 years before getting cancer. It was a job he was always fond of. After he got the clearance to work again he got a job at the McKinleyville Services District doing maintenance around town. He loved his job and the ability to be outside doing something different everyday.

When sickness inhibited his ability to work a normal job, he focused on his hobbies. He was an avid fisherman. You could often find him climbing the rocks at the North Jetty to fish, or crabbing in the bay with Shirley. He also enjoyed woodworking. He was known for his redwood planter boxes that he would sell locally. He would even make a birdhouse from time to time, but usually only upon special request. He loved spending hours in his backyard crafting different boxes.

If you really knew Mark you would know that his other love was music, specifically heavy metal. He spent hours finding new bands to support online, even going to see a few of them in concert when they came to the states. He was definitely a real metal head. In his later years he also began collecting antique bottles. Mark and Shirley loved spending a weekend at a bottle show or scouring antique shops for bottles. They were happily welcomed into a wonderful group of northern California bottle collectors. Their collection is proudly displayed in their home.

Our family would like to make a special thank you to his entire team at UCSF medical center, especially Doctor Gansler. They provided many years of support and kindness when the hospital became a second home. Doctor Gansler was much like a second mother to Mark and he trusted her with his whole heart. It’s not often you are blessed to have the same team of people surrounding you for almost 20 years. Our biggest hope is that the research they were able to do on his case would help to save someone else in the future. Our family would also like to thank Dr. Cobb and his team. They have been like family to us and we don’t know where we would be without him. A special thanks also needs to be given to Providence in Home Healthcare. The team there provided Mark with such wonderful care to make him comfortable at home.Especially Sophia, Terrance, and Gina who went the extra mile every time Mark needed anything.

Mark is survived by his mother Jessie Desadier, brother Rodney Summers, wife Shirley, his children Max (Catrina), Rex, and Lindsey (Grady) and his grandsons Jaxson and Tristan; and his mother and father-in-law Judy and John Wolff. He is preceded in death by his father Robert Maillie, his brother-in-law John W. Wolff, his grandmother Percilla Madison, and many aunts and uncles.

Services for Mark will be held August 26 at 12 p.m. at Azalea Hall in McKinleyville.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Mark Maillie’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

BOOKED

Today: 10 felonies, 10 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom signs Executive Order to assist Imperial County’s recovery following 2025 August Monsoon Storms

RHBB: Body Recovered Off Humboldt Coast After Fisherman’s Discovery

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom on Republicans losing challenge to new Congressional maps at U.S. Supreme Court

KINS’s Talk Shop: Talkshop February 4th, 2026 – Steve Madrone

New Owner of Singing Trees Recovery Center Arrested for DUI and Child Endangerment, and in Odd Interview She Denies That the State Revoked Her Therapy License. (It Did.)

Ryan Burns / Thursday, July 6, 2023 @ 5:41 p.m. / Community Services , Crime

Singing Trees Recovery Center, located just north of Richardson Grove State Park. | File photo.

###

###

Less than a month after reopening Singing Trees Recovery Center, new owner Amber Rose Bedell, age 45, was arrested on the Fourth of July and booked into the Humboldt County jail on charges of driving under the influence of alcohol and child endangerment.

This was Bedell’s third DUI arrest since 2016 and her second for child endangerment, according to state and county records.

Bedell is the founder of Pure Solution Family Services, Inc., a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization founded last year. It’s through that organization that Bedell is operating Singing Trees Recovery Center, a drug detox and rehab facility located in Southern Humboldt.

Formerly a marriage and family therapist, Bedell had her MFT license revoked in 2018 when the state’s Board of Behavioral Sciences found that she had failed to report a criminal conviction stemming from an incident in September of 2016. Read the revocation order here.

According to that order, Bedell was arrested and later convicted for driving 88 miles per hour with a blood alcohol level of 0.29 percent, more than three and a half times the legal limit.

Bedell has had several more run-ins with the law since then. In a somewhat convoluted incident from June 2018, deputies responded to a pair of stolen vehicle reports connected to a McKinleyville residence and to Bedell, who was already under investigation for child endangerment, according to a press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office. While searching the residence, deputies allegedly found a loaded firearm, heroin, syringes, marijuana and drug paraphernalia, all in an area accessible to children.

At the time, Bedell was director of another public benefit nonprofit called Evolve Youth Services. She has not been affiliated with that organization for four or five years now, according to its current treasurer, Paul Rodrigues.

In January of 2020, Bedell was arrested again for driving under the influence of alcohol resulting in injury.

Reached by phone this afternoon, Bedell was hesitant to discuss the matter, saying she would release a statement after speaking with her attorney and East Coast PR team.

“You understand the implications and what this looks like, the seriousness of what this looks like on paper … ,” she said, adding that false things have been printed about her in the past. “I want to work with you, and I want you to work with me, too. I don’t want that facility to be in any danger. I don’t want people who need help to not benefit from the quality and amazing program we have. I know you don’t want that either.”

She added, “As you know, an arrest does not mean a conviction.”

When told that we planned to publish a story today, Bedell requested an hour to feed her kids and make some phone calls. Reached again an hour later, she said she couldn’t comment on the July Fourth incident except to say that it will have no effect on the operation of Singing Trees.

“It’s open and we have a resident moving in,” she said.

She went on to deny that the state had revoked her marriage and family therapy license, saying she relinquished it voluntarily because she no longer needed it, “but I didn’t follow the proper channels.”

We asked her to explain further.

“When you have a license for anything … and you want to not have it anymore, you have to do a process,” she said. “You can’t just not do it. So I paid my fee to renew my license and then I made the decision upon consultation [with a colleague] not to go through the process of continuing with that. And I didn’t turn in the correct paperwork for that because I wasn’t aware [I needed to].”

Asked if she had any proof that she’d voluntarily relinquished her license, anything she could send to us, she replied, “What would that even look like?”

We asked her why the California Board of Behavioral Sciences maintains a published ruling saying her license was, in fact, revoked, and Bedell again insisted that she had already relinquished her license by that time.

“It’s really what happened!” she said. “I thought, ‘Okay, I don’t need this license anymore and I don’t want it because this isn’t what I do anymore.’ I don’t do traditional therapy, I don’t bill insurance. I had moved on from that. I knew that there was gonna be a lot of hoops to jump through, but that [state ruling] hadn’t happened yet when I made that choice.”

Asked about the underlying criminal charges — driving 88 with a 0.29 percent blood alcohol content — Bedell acknowledged that it happened but again said she had already voluntarily relinquished her license by that point.

We then asked her about the 2018 arrest for child endangerment. “I’m not sure if I’m ready to talk about all of that,” Bedell said, adding that “incorrect information” about the incident had been printed at kymkemp.com. However, it seems she was referring to publication of a press release issued by the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office and published by Kemp as well as the Outpost and the Times-Standard.

What was incorrect in that press release? Bedell said the charges mentioned were later dropped and that she, personally, had not reported the cars stolen, though the press release doesn’t say she had.

Asked if there was anything else she wanted to say, Bedell took some time to think through and recite a statement. Speaking slowly and deliberately she said, “We are very excited to have Singing Trees open and to provide quality substance abuse treatment services to our community from a holistic approach.”

She then wrestled with what to say about her latest arrest, at one point requesting this reporter’s help. Finally, she ventured forth on her own: “The event on July Fourth of 2023 is still under investigation. There are not official charges from the District Attorney — .”

She cut herself off there, mid-sentence: “No no no. I can’t talk about this.”

Before the conversation ended, Bedell returned to the matter of Singing Trees.

“We are still open,” she said. “We have residents moving in now and we are accepting new patients and there is no impact on the operations of the facility in any manner whatsoever.”

California and Manufacturers Strike Deal Over Zero-Emission Trucks

Rachel Becker / Thursday, July 6, 2023 @ 2:45 p.m. / Sacramento

A fleet of new Tesla big rigs was on display at PepsiCo’s Sacramento facility on April 11, 2023. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters.

Truck manufacturers won’t file legal challenges over California’s controversial mandate, and in return, the state air board will relax some smog-fighting requirements.

California and major truck manufacturers announced a deal today that would avoid a legal battle over the state’s landmark mandate phasing out diesel big rigs and other trucks.

In return, the Air Resources Board will relax some near-term requirements for trucks to reduce emissions of a key ingredient of smog to more closely align with new federal standards.

“It’s great to have them not suing and not helping others in lawsuits,” said Steven Cliff, the air board’s executive director. “But more important is we ensure that we’re getting the actual reduction benefits associated with the rules.”

The powerful Truck and Engine Manufacturers Association as well as 10 manufacturers, including Cummins, Inc., Daimler Truck North America, Volvo Group North America and Navistar, Inc. signed on to the deal.

“Both (the California Air Resources Board) and we realized that, through these discussions, there was an opportunity for CARB to realign with the (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) starting in 2027. And that’s really what led to our sitting down and coming to this agreement,” said Jed Mandel, president of the Truck and Engine Manufacturers Association.

Starting in 2036, no new fossil-fueled medium-duty and heavy-duty trucks will be sold in California under a regulation approved by the air board in April. All new models will have to instead be zero-emissions. Large trucking companies also must convert existing fleets to zero-emission electric or hydrogen models by 2042.

“It’s great to have them not suing and not helping others in lawsuits. But more important is we ensure that we’re getting the actual reduction benefits associated with the rules.”

— Steven Cliff, executive director of the California Air Resources Board

While manufacturers are now supporting California’s rules, trucking companies have vigorously opposed them, saying zero-emission big rigs can cost more than twice the cost of a diesel truck, take hours to charge, can’t travel the range that many companies need to transport cargo and lack a sufficient statewide network of charging stations. A top executive of the trucking industry had predicted economic chaos and dysfunction and said the mandate is likely to “fail pretty spectacularly.”

Vehicle pollution battles are high stakes in California: Under the federal Clean Air Act, the state has the unique authority to set vehicle emissions regulations that are stricter than the federal government’s. More than a dozen other states usually choose to follow California’s lead.

Engine manufacturers fought against an earlier state truck rule, enacted in 2020, that cut smog-forming pollutants from medium and heavy duty trucks, warning that the rule was not cost-effective and would harm California’s economy.

When the federal Environmental Protection Agency adopted its own rules to cut smog-forming pollutants from trucks in December 2022, manufacturers were faced with the possibility of a split market, with California enacting different rules.

Under the new agreement, California will bring its 2027 standards for smog-forming nitrogen oxides more in line with the federal version.

Truck and engine manufacturers also will be allowed to sell a higher percentage of older diesel technology that isn’t as clean burning between 2024 and 2027, provided they offset the emissions, such as by also offering up a comparable number of zero-emission engines. The air board also agreed to give manufacturers four-years warning before implementing new clean trucks rules.

In return, the truck manufacturers agreed not to sue over California’s suite of clean trucks rules or weigh in on lawsuits brought by other parties, and said that they would follow the rules regardless of how any other lawsuits resulted. If trucking companies sue the state, for instance, they won’t have the support of truck engine manufacturers, a powerful group.

The agreement calls for changes to the state’s current rules that will still require a formal rulemaking process and a vote of the board. Cliff said the staff has a strong case to make to the board about the changes.

Danny Cullenward, an energy economist and research fellow with American University, said the agreement is an unusual strategy, but given the legal uncertainty of a lawsuit in the current federal court system, he understands the rationale.

“It’s kind of like regulating through contract, which is a little weird,” said Danny Cullenward, an energy economist and research fellow with American University. “Deals get made all the time. This one is just written down in advance.”

California has struck similar deals before, when the state crossed swords with the Trump administration over its power to set greenhouse gas limits for tailpipe pollution.

Cullenward said the move makes it less likely that California’s clean truck efforts will become mired in lawsuits that eventually end up in front of the Supreme Court.

“The Supreme Court has gone from conservative to reactionary and aggressive, and I mean, lawless,” Cullenward said. “There’s more to be said, practically, from avoiding that drama.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

Tonka, the 11-Year-Old Camel Who Lived at Miranda’s Rescue and Was Best Friends With a Miniature Donkey, Died Last Week

Stephanie McGeary / Thursday, July 6, 2023 @ 11:41 a.m. / Animals

Miranda and Tonka at Miranda’s Rescue | Images provided by Shannon Miranda

###

Tonka – the beloved camel who lived at Miranda’s Rescue in Fortuna for the last decade – died last week after a long struggle with a bacterial infection.

“With a very heavy heart, we regret to say that we have lost Tonka, our amazing sanctuary animal, the camel,” Miranda’s Rescue posted on its Facebook page last week. “Unfortunately, he had some sort of bacterial infection that took him fast and there was nothing we could do to save him. He was an icon to the ranch and loved by so many.”

Reached by the Outpost on Wednesday afternoon, the rescue shelter’s founder Shannon Miranda said that he doesn’t know the name of the bacteria that ultimately killed Tonka, but that the camel had been born with the issue and there wasn’t a cure.

Though he usually seemed healthy, Tonka would occasionally have flare-ups from the infection, which would cause him to have terrible diarrhea. Miranda had to regularly give Tonka an oral medication, which would clear up the issue and everything would be fine again. But this time, Miranda said, the flare up just got so bad, Tonka was beyond the point of treatment and had to be euthanized. The vet had warned Miranda that Tonka’s infection would eventually get worse, so he knew this moment would come. But Miranda said he was still not expecting to lose the animal so soon.

Tonka had come to Miranda’s rescue when he was just one year old and had lived on the ranch until the day he passed at age 11. Originally a petting zoo animal, Tonka was brought to the shelter when his previous owner, Jenna Kilby, was no longer able to care for him. Though Kilby couldn’t keep Tonka with her, she maintained a close relationship with the camel, coming to visit him at the shelter all the time, Miranda said.

Miranda also had a very special bond with Tonka, he said, and was really the only one at the shelter who was able to handle him. Though camels are great animals, Miranda said, they can also be a bit ornery and usually require a lot of training to be able to be handled by humans. Miranda tried to train Tonka, but said that with all the other animals at the shelter, it was difficult to provide Tonka with the amount of training he needed.

Though Tonka was not a fully trained camel and wouldn’t let just anyone into his enclosure, he was very friendly with people who just wanted to visit him from outside of the fence. He was very popular with visitors at the ranch, Miranda said, and was happy to get pets and treats, especially bread, carrots and apples.

Aside from Miranda and Kilby, Tonka had also developed a special relationship with his best friend, a miniature donkey named Blossom. Tonka and Blossom would run around together and whenever Miranda had to groom Tonka or give him medical care, Blossom had to be there to help Tonka stay calm.

“Every time [Blossom] was out of his sight, he would get really upset,” Miranda said.

Despite his medical issue and his occasional “grumpiness,” Miranda said, Tonka lived an overall healthy and happy life and will be missed deeply by everyone at the ranch and many members of the community. Eventually Miranda hopes to find another camel to live at the ranch. But for now he is still getting over the death of his beloved Tonka. Though losing animals is a part of the territory when running a shelter, Miranda said that Tonka was very special to him and this was a particularly difficult loss.

“It’s so sad because he was a fixture out there,” Miranda said. “When he passed, I just sat out there with him and I just cried like a baby. I was so overcome with sadness…I want to thank everybody who loved Tonka that came out to see him. I know he’ll be really missed.”

McKinleyville Homicide Suspect Arrested Near College Cove, Following Citizen’s Tip

LoCO Staff / Thursday, July 6, 2023 @ 9:51 a.m. / Crime

PREVIOUSLY:

- Suspect in Tonight’s McK Homicide Named; Residents Urged to be Vigilant

- Sheriff’s Deputies Still Searching for McK Homicide Suspect; North County Residents Urged to Take Precautions

###

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

On 7/3/2023, Deputies with the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office investigated a suspected homicide involving a firearm in the 2000 Block of Silverbrook Ct., McKinleyville. The firearm used was reported to have been a shotgun. The suspect, later identified as Jasen Dwain COLEY (age 26 of McKinleyville), fled from the scene in a dark-colored compact sedan. The vehicle was located later that evening by HCSO Deputies on patrol in the Frontage Road parking area of Strawberry Rock, Trinidad. The vehicle was unoccupied, and COLEY was not immediately located. COLEY was believed to be in possession of a firearm.

An extensive search of the area of Strawberry Rock and the surrounding trail systems was conducted over the course of two days utilizing foot patrols, vehicle patrols, and a UAV drone. The search was unsuccessful in locating COLEY.

A No-Bail, Ramey Warrant was issued for COLEY’s arrest in the charge of PC 187(a): Murder.

On 7/5/2023 at about 1735 hours, a citizen came upon a male subject laying in the brush along the trail system between Trinidad State Beach and College Cove, Trinidad. The subject was reported to have a shotgun next to him. The citizen left the area and alerted Law Enforcement. Based on the physical description of the male subject provided by the reporting party, the subject was believed to be COLEY. HCSO Deputies and California State Parks Rangers responded to the area described and located a male subject matching the description given.

The subject identified himself as Jasen COLEY and was taken into custody without incident. A 12 gauge, Remington 870, shotgun was located with COLEY’s belongings on scene. The shotgun was found to be loaded with one (1) Fiocchi Brand, 7/8 oz slug. The shotgun recovered is believed to be the firearm used in the Silverbrook Ct. homicide on 7/3/2023. There are no known outstanding firearms relating to this case. A registration check of the shotgun’s serial number returned with no owner record on file.

COLEY was transported to the Major Crimes Division of the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office where he was interviewed by Investigators from the HCSO and Humboldt County District Attorney’s Office. COLEY was booked into the Humboldt County Correctional Facility on the charge of PC 187(a): Murder and is being held without bail pending arraignment.

COLEY and the victim, Kenneth “Michael” DAVIS (age 25 of McKinleyville), were known to each other. The motive for this crime is still under investigation. The case is being submitted to the Humboldt County DA’s Office for prosecution.

Thank you to our partners with California State Parks, Eureka Police Department, California Highway Patrol, and Humboldt County District Attorney’s Office for their collective assistance in this investigation.

Photo via HCSO Twitter.

California Wants More College Students to Graduate Debt-Free. How’s the Middle Class Scholarship Going So Far?

Mikhail Zinshteyn / Thursday, July 6, 2023 @ 7:19 a.m. / Sacramento

Students walk near Meiklejohn Hall at California State University East Bay on Feb. 25, 2020. Photo by Anne Wernikoff for CalMatters.

California cemented its status among the most affordable states to earn a bachelor’s degree after lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom fulfilled their promise to expand the state’s Middle Class Scholarship program by another $227 million in this year’s budget deal.

That overhauled scholarship, which debuted last year, is now a $859 million juggernaut. It’s also a growing slice of the state’s financial aid pie: Between 2016 and 2022, California lawmakers poured roughly $1.4 billion more into grants and scholarships, bringing the state’s total contribution to around $3.5 billion.

Using new data that examines how the Middle Class Scholarship helped students in its first year, a CalMatters analysis shows that the grant worked largely as intended, sending more money to students of higher-income families.

But the program has frustrated some advocacy groups, who want the state to spend more on lower-income students, especially those who are ineligible for existing state financial aid. For lawmakers grappling with a shaky state financial outlook while also attempting to rein in the cost of college, this is a tough needle to thread.

The scholarship itself had growing pains in its first year. Many students who expected aid at the start of the 2022-23 academic year received their money months later as campuses and the state agency running the program rushed to jump-start a complicated program in a short amount of time.

Here’s the latest information and what you need to know about financial aid in California.

Who got new Middle Class Scholarship money — and how much

Because of the Middle Class Scholarship, 302,000 students received an average of $1,970 more dollars toward their education in the 2022-23 academic year, according to data CalMatters obtained from the state’s financial aid agency, the California Student Aid Commission.Students from families with higher incomes received more money than those from lower incomes by design. That’s because students from wealthier families receive less financial aid from other sources. The scholarship uses a formula that takes the total cost of college and deducts how much a student receives in financial aid. It also assumes a student works enough to earn about $8,000 a year. For dependent students in households that earn more than $100,000 annually, an added formula is used to calculate how much their families can pay toward college. The assumption is that wealthier families have more money than poorer families to commit to college.

Students whose family incomes were between $150,000 and $200,000 received an average Middle Class Scholarship of roughly $2,800 — it was higher for UC students. For students whose families earned less than $50,000, their average scholarship was around $1,400.

Students will likely get more money going forward as the scholarship grows by another $227 million.

The scholarship complements the state’s marquee financial aid tool, the Cal Grant, which covers the in-state tuition for UC and CSU students and provides cash aid to community college students. Students generally are eligible for both aid programs for up to four years of full-time enrollment.

The middle class scholarship is available to a far larger swath of students: those whose families earn as much as $217,000. The income cut-off for the Cal Grant is lower. Students in a family of four will receive a Cal Grant in 2023 if their families earn no more than $125,600, depending on the type of grant.

Lawmakers intend to eventually grow the scholarship so that any student who gets the state aid won’t have to borrow to attend a UC or CSU, a public university debt-free promise. That would require around $2 billion more dedicated to the scholarship annually. Last year, the program was funded at about a quarter of its capacity, so students received about a quarter of the full amount they would have been awarded under the scholarship.

Different financial aid helps different students

But while the scholarship widens its reach to more students, it shuts out students who attend community colleges, as CalMatters previously reported.

Community college students are among the state’s poorest to pursue higher education. And though California posts the lowest community college tuition in the country, community college students still must find ways to afford rent, food and transportation.

Because students attending UC and Cal State campuses have access to more state, federal and institutional financial aid, often community college students end up paying more for their education than students enrolled at California’s public universities, according to a series of reports by the California-based Institute for College Access & Success.

Leaving out community college students from the debt-free promise of the Middle Class Scholarship excludes most of California’s public postsecondary students, who outnumber UC and CSU students nearly 3 to 1.

“It is critical that California approach college affordability equitably by prioritizing students with the least resources.”

Education Trust — West and the Institute for College Access & Success

Lawmakers have expanded the Cal Grant to more than 100,000 additional community college students in recent years, but the state is due to decide next spring whether to expand the aid program so that practically any student with low-enough family income could get the grant, which follows students to a UC or CSU if they transfer. A key unknown: whether the state will have the funds to do it.

Some advocates think the state should put a pause on growing the Middle Class Scholarship and instead continue expanding the number of students eligible for the Cal Grant, including community college students.

“It is critical that California approach college affordability equitably by prioritizing students with the least resources,” Education Trust — West and the Institute for College Access & Success wrote in May. “Fully funding Cal Grant reform instead of (Middle Class Scholarship) is by far the best approach.”

California supports more low-income students than other states

But while the state’s students from modest means already benefit a lot from financial aid, middle-class families often shoulder a larger load of college costs.

Federal education data analyzed by CalMatters tells the tale.

Depending on which income bands you look at, California ranks fourth or fifth among all states in how much students from families earning less than $75,000 had to pay for expenses like tuition, housing and food after deducting all their state, federal and campus financial aid — a concept known as “net price.”

However, affordability plummeted for students whose families earned more than $110,000. For that group, California ranked 42nd, meaning they received considerably less aid. Still, as a percentage of income, students from wealthier households need to spend less of their family earnings on college costs than students from lower-income families, other data shows.

The federal data is from 2020-21 — the most recent available — and captures all first-time, full-time students who got some kind of federal grant or loan that year.

Among the “net price” highlights for UC and CSU students:

- California students with family incomes between $30,000 and $48,000 needed to pay an average of $7,800 — about $3,200 less than the U.S. average;

- For California students with incomes above $110,000, the net price was around $21,000 — $1,800 above the national average;

- The public can look up this “average annual cost” data by school using the College Scorecard tool.

Middle Class Scholarship expected changes and lingering problems

One expected change is that students formerly in foster care won’t have to borrow starting this fall, as long as they work part-time. They will begin receiving their full scholarship, a new social commitment in this year’s budget deal that should benefit roughly 600 students annually at a cost of around $5 million each year.

A problem that may continue for most other students, though, is that the mechanics of that scholarship complicate how quickly students actually receive the money.

Every Cal State student and some UC students didn’t receive their Middle Class Scholarship money until late 2022 or early 2023, meaning the dollars promised to them for early fall term never arrived, according to data CalMatters obtained from the California Student Aid Commission.

Why? The state discovered how difficult it was to run a new financial aid program that’s unable to determine how much money a student deserves until all that student’s other aid is calculated. Not to mention that suddenly 300,000 students were eligible for the revised scholarship.

The Middle Class Scholarship is a “last-dollar” cash award. How much a student gets is a basic math problem: the total cost of attendance, minus all other financial aid, minus the $8,000 from working and minus the family contribution from students whose households earn more than $100,000.

When the scholarship debuted last summer, campuses and the student aid agency running the program scrambled to accurately tally the amount each student would get.

“As a result, students and families were not notified of their award amounts in time for it to influence their enrollment decisions or their financial planning around covering college costs,” the Legislative Analyst’s Office wrote. The student aid commission said students who didn’t get scholarships in the fall saw that money the following term along with the remaining funds promised to them.

A further complication: If students receive additional money during the school year, they have to give back an equal amount of the Middle Class Scholarship aid.

Some of that confusion is set to go away, both because the scholarship has had a year of being implemented and because of a new bill awaiting Newsom’s signature. It would allow students with emergency expenses — such as several hundred dollars to repair a car, pay rent or afford a medical procedure — that also get campus emergency aid to avoid having that count against their total financial aid.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

My House or My Beach? Why California’s Housing Crisis Threatens Its Powerful Coastal Commission

Ben Christopher / Thursday, July 6, 2023 @ 7:13 a.m. / Sacramento

California lawmakers have been busy over the last decade trying to make it easier to build homes across a housing-strapped state. But there’s an 840-mile-long exception.

In an undulating band that generally runs 1,000 yards from the shoreline, the 12 members of the California Coastal Commission have the final say over what gets built, where and how.

Voters empowered the commission to protect the state’s iconic beaches in 1972, responding to a crisis of despoiled seas and the prospect of the Miami-fication of the California coast.

But five decades later, the state faces a different crisis as millions of Californians struggle to find an affordable place to call home. Now, a growing number of legislators and housing advocates are trying to wrest away some of the commission’s power.

Legislation by San Francisco Democratic Sen. Scott Wiener would fast-track apartment development in parts of the state that haven’t met their state-set housing goals, exempting them from lengthy public hearings and environmental legal challenges. The coast is no exception, effectively cutting the Coastal Commission out of the process.

Commission members, staff and environmental advocates say the bill may be the most direct assault yet at the agency’s voter-backed mandate.

“Once you start exempting classes of development from the Coastal Act there will be no shutting that barn door,” said Sarah Christie, a lobbyist for the commission. “You’re going to lose some of the best things about California.”

And as rising seas threaten to bring down bluffs and flood beachfront neighborhoods, coastal advocates argue that carefully considered development is more important than ever.

Wiener and his allies reject the argument that the commission is the only thing standing in the way of a development free-for-all, since current zoning rules and environmental protection laws would still apply. Ending what has become the regular practice of exempting the coast from California’s most aggressive pro-housing development laws is also fair, they argue. California’s beachfront happens to be home to some of the state’s richest residents.

“The coastal zone is much whiter and wealthier than the rest of the state,” Wiener noted at a recent Assembly committee hearing. “The idea we would be applying state housing law inland…while we literally exempt whiter, wealthier coastal communities is offensive to me.”

Wiener said he plans to introduce tweaks to the bill before its next hearing on July 10 in an effort to “compromise” with the commission. But the two sides remain far apart.

“The idea we would be applying state housing law inland…while we literally exempt whiter, wealthier coastal communities is offensive to me.”

— State Sen. Scott Wiener, Democrat from San Francisco

The tension between the state’s aggressive housing goals and its longstanding commitment to coastal preservation is particularly acute in Southern California, where the latest round of state housing goals shifted the bulk of the region’s planned growth from inland communities — the traditional, sprawling outlets for pent up housing demand — to coastal ones. That includes cities like Santa Monica, Malibu, Los Angeles, Encinitas and San Diego, all of which fall at least in part, if not entirely, within the coastal zone.

“If you have the Coastal Commission, with their ‘less is more’ mindset saying, ‘no, you can’t build here’…how are cities even supposed to attempt to achieve meeting that (housing) goal?” said Elizabeth Hansburg, executive director of People For Housing, a pro-housing advocacy group in Orange County.

Christopher Pederson, who served as chief counsel for the commission before retiring in 2018, said it’s possible for the state to build up the coast while maintaining “really strong protections” in undeveloped coastal land and for delicate ecosystems. In fact, he said, if the alternative to building in dense coastal cities is encouraging car-oriented sprawl in the exurbs, the two goals may necessarily go hand in hand.

“From an environmental perspective, from a climate policy perspective, from a housing perspective and from a transportation perspective, I think it makes a lot of sense to encourage more multifamily housing in the coastal zone,” said Pederson.

Will the Coastal Commission hold the line?

This isn’t the first time the Legislature has taken a crack at the Coastal Commission’s authority. It’s not even the first time this year.

San Diego Assemblymember David Alvarez, a Democrat, introduced a bill in February that would encourage developers to set aside units for lower income residents by allowing them to build higher and denser projects. The bill builds on past “density bonus” policies that have made their way through the Legislature. But unlike its predecessors — and unlike some of the most significant housing bills in recent years, including one that allows the construction of duplexes in areas zoned for single family homes across the state — Alvarez’s bill explicitly went out of its way to include the coastal zone.

Then, in April, the bill reached the Assembly Natural Resources Committee and a coastal exception was added back in.

Chair Luz Rivas of Arleta, and other Democrats including Gail Pellerin of Santa Cruz and Dawn Addis of San Luis Obispo, made clear at the hearing that overriding the commission was a no-go.

Alvarez accepted the change rather than see his bill die. But he was visibly frustrated.

“I heard a statement that coastal access is important and that people should have the opportunity to visit the coast,” he said, referring to one of the commission’s key mandates to keep California beaches open to the public. “People should also have the opportunity to live on the coast, not just visit the coast.”

“The ocean is coming”

So far Wiener’s bill has not met the same fate, though it goes before the same committee later this month. His bill also, arguably, represents a bigger challenge to the commission’s authority.

In most of the state’s cities and counties, proposed multiplexes and apartment projects are allowed to skirt lengthy public approval processes. Instead they get automatic approval as long as they check the right boxes — among them, offering a certain share of units at below-market rents or prices and abiding by stricter labor standards.

But the Coastal Commission doesn’t do box checking.

Along much of the coast, the commission has to approve city growth and zoning plans. In neighborhoods especially close to the water, foes of proposed developments can appeal directly to the commission.

And in cities that haven’t come up with their own coastal protection plans, which includes about a quarter of coastal cities including Los Angeles, the Coastal Commission enforces the law alone, armed only with the Coastal Act. And the act itself is fairly light on specifics.

That’s for good reason, said Christie, the commission lobbyist.

Ensuring that a proposed development is built “far enough away from an eroding bluff that it’s not going to fall into the ocean in 20 years, there is no objective standard that can speak to that complexity,” she said.

“It’s going to be a managed retreat or an unmanaged retreat because the ocean is coming and nature bats last.”

— Sarah Christie, lobbyist for the Coastal Commission

Climate change and rising sea levels add yet another level of complexity and another reason not to rush development, she added.

“The last thing that California should be doing is concentrating more new development in these hazardous flood-prone areas,” she said. “It’s going to be a managed retreat or an unmanaged retreat because the ocean is coming and nature bats last.”

That view is shared by all 12 members of the commission, who are appointed by the governor or the Legislature.

“We take a lot of time and effort in evaluating each and every project that comes before us,” said Commissioner Dayna Bochco during a June 7 hearing. “You can’t just make a mathematical formula as to what works in any given project on the coast.”

The commission voted unanimously to oppose Wiener’s bill.

Must fit plans for California coast

The bill does include its own set of checks on which projects get the red-carpet treatment and which get closer review.

In order to receive the fast-tracked approval process, the land in question already has to be zoned by local governments for housing. A proposed building has to have pre-existing “urban” development on at least three of its four sides.

According to estimates put together by California YIMBY, a pro-housing development organization that supports the bill, of the nearly 1.5 million acres within the coastal zone, the bill would allow for streamlined development on just 277,160 acres. The vast majority of the land — wetlands, floodplains, beaches and river channels — either are explicitly exempted from the bill or aren’t zoned for housing by locals.

“Approximately 85% of the Coastal Zone is already excluded from the bill. The remaining 15% are existing urbanized, developed communities,” Wiener said in a written statement. He added that the state “can’t afford to continue excluding these areas if we are to meet our climate goals — the lack of housing in coastal zones these exclusions produce already means coastal workers have to drive 10% more on average than their inland counterparts.”

Senator Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco, announces legislation to provide refuge to out-of-state transgender kids and their parents at the Capitol on March 17, 2022. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters.

Wiener and his allies also reject the idea that proper planning for rising oceans requires detailed, site-by-site analysis. The senator’s office pointed to voluntary planning guidelines produced by the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission and San Mateo County Flood Control District. The San Mateo County planning document builds on nationwide flood risk mapping from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Though his office has yet to provide details, Wiener said his proposed compromise language to the Coastal Commission includes preserving the current discretionary review process for the most at-risk slivers of the coast and adding specific “objective development standards” around rising sea levels.

Not that anyone can say with certainty how much shore the sea is likely to swallow across the entire coast in the coming decades.

“Everybody admits that it’s not a hard science, it’s probabilities,” said Joseph Smith, a land-use consultant for California Coastal Works who advises developers and governments navigating the Coastal Act. “But if it is absolutely important to get housing into the coastal zone, then yes, you could pick a number.”

Building a California coast for all

The commission and its defenders say pro-housing advocates and legislators are picking on the wrong enemy.

For the first decade of its life, the Coastal Commission was empowered to make the construction of affordable housing a condition of its approval of residential projects. In 1981, the Legislature took that power away over the commission’s objections.

Revoking that power will “make sure that the ability to live near the coast is reserved for the wealthy,” then-Chairman Lenard Grote warned at a legislative hearing at the time.

Susan Jordan, founder of the nonprofit California Coastal Protection Network, is a familiar face at the state’s public hearings, where she regularly challenges oceanside projects for violations of the Coastal Act. A recent win: the Poseidon Water desalination project in Huntington Beach, which the Coastal Commission rejected last year.

“The Legislature ‘broke’ it and now it needs to ‘fix’ it,” Jordan said in a statement.

The commission’s supporters regularly stress that it has never rejected a proposed affordable housing project.

But for many developers — including those who build deed-restricted units for lower-income residents — the possibility of years of delay with no certain outcome has created a “chilling effect,” said Jeannette Temple, a San Diego land use consultant.

“If you’re an affordable housing developer, you’re already operating on the margins, so most of the time my clients, and people my clients know, don’t even look in the coastal zone,” she said. “In my opinion it’s just another kind of redlining.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.