Stakeholders assemble to discuss the science behind the Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project.

Stakeholders assemble to discuss the science behind the Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project.

Scientists and government employees generally aren’t known as party animals, but there was definitely a festive mood yesterday at the Fortuna River Lodge as close to a hundred stakeholders gathered to celebrate the progress being made restoring the Eel River estuary. Roughly three decades of work has already gone into restoration, and there’s still a lot of ecological work needed to repair an estuary impacted by generations of dike-building, ditch-digging and sedimentation. But the biologists, engineers, nonprofit leaders and property owners on hand Thursday sounded optimistic.

Wiyot Tribe member Vincent DiMarzo delivered the welcoming remarks, explaining as the crowd sipped coffee that “Wiyot” is the local tribe’s word for the Eel River itself. It means “bountiful,” DiMarzo said, adding, “To see the river the way it is now is tough for me.”

The Eel was once one of the largest salmon-producing rivers in the state, and much of the delta’s river system was deep enough to host hundred-ton shipping vessels carrying goods from San Francisco and beyond. A hundred and fifty years ago, the delta’s river system would drain naturally with the rains and tides. But in seeking to manipulate the land to improve agriculture, people altered the estuary, diking off natural tributaries and digging channels to direct drainage. Over the subsequent years, these altered channels began to fill with the steady flow of sediment washing off the highly erosive Wildcat Hills, impacting the tidal prism and, ironically, leading to frequent flooding of the region’s agricultural land.

Former Humboldt County Supervisor Jimmy Smith is considered one of the most influential leaders in restoration efforts for the estuary. Standing before the crowd yesterday he remarked that next year will be his 20th working on Eel River restoration projects. Smith recalled going door-to-door in 1995, when he was running for a seat on the Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District, and hearing from landowners in the Eel River Valley who were concerned about flooding, wastewater problems and acres lost due to lack of drainage.

“Agricultural land in the county was underwater for months at a time,” Smith said. “People were angry.” In fact, the Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project, the delta’s most extensive and complex restoration project to date, was instigated by landowners. Nearly two decades later, Smith is impressed with the progress and excited about the potential.

“I think this will be the most successful, largest restoration ever in Northern California,” he said. “These projects not only benefit habitat; they allow working lands to continue into the future.”

After presentations at the River Lodge, attendees piled into government-issue SUVs and drove out to several project sites.

After presentations at the River Lodge, attendees piled into government-issue SUVs and drove out to several project sites.

The relationship between conservationists and landowners has often been an uneasy one. Katherine Ziemer, executive director of the Humboldt County Farm Bureau, said she was surprised to even be invited to speak yesterday. “We’ve been, if anything, an impediment,” she remarked. Many of the area’s landowners, she said, have felt disrespected and overlooked during much of the planning and implementation of these projects. She noted that only one landowner, grass-fed-cattle rancher Jay Russ, was among the day’s long list of speakers. “I think in the future we could be better partners,” Ziemer said.

The next speaker, Paula Golightly of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, offered an anecdote to convey the uneasy dynamic between scientists and landowners. Golightly said she had gone out to meet with a rancher named Larry — “hands the size of dinner plates,” she said. Larry invited her to step into his office, gesturing toward the cab of his full-size pickup. She climbed in on the passenger side and shut the door. Larry turned to her, Golightly recalled, and said, “I gotta tell you something, little lady: You scare the hell outta me.”

Without landowner cooperation, most of these restoration projects would be impossible. Landowners, meanwhile, don’t want to be forced into actions that could harm their land and livelihoods.

But Jay Russ, the local cattle farmer, said the projects here have been designed as win-win propositions. Standing with his thumbs looped into the pockets of his blue jeans Russ said, “From an agricultural point of view, flood control and improved drainage is what pays our bills.” Farmers like him get money from agricultural production and shouldn’t be held responsible for upholding the Endangered Species Act, he argued. But he feels that, here, at least, both goals can be achieved simultaneously. “We will find a common solution,” he said.

Allan Renger, fish biologist with the California Department of Fish & Wildlife, explains how conservationists are using fine-mesh netting to monitor fish in the Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project.

Allan Renger, fish biologist with the California Department of Fish & Wildlife, explains how conservationists are using fine-mesh netting to monitor fish in the Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project.

After lunch, attendees of the event climbed into a line of government SUVs and headed out for a tour of some of the project sites. Programming for the day focused on three major projects, each in a different stage of completion.

The Eel River Estuary Preserve project (pdf) “seeks to restore salmon rearing habitat, riparian function, water quality and fish passage while creating a mosaic of pasturelands and natural landscapes.” It’s also designed to enhance agricultural uses such as livestock grazing while reducing the impacts of climate change and enhancing recreational uses. The total project cost of just over $1 million has been provided by two grants, one from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the other from the State Coastal Conservancy.

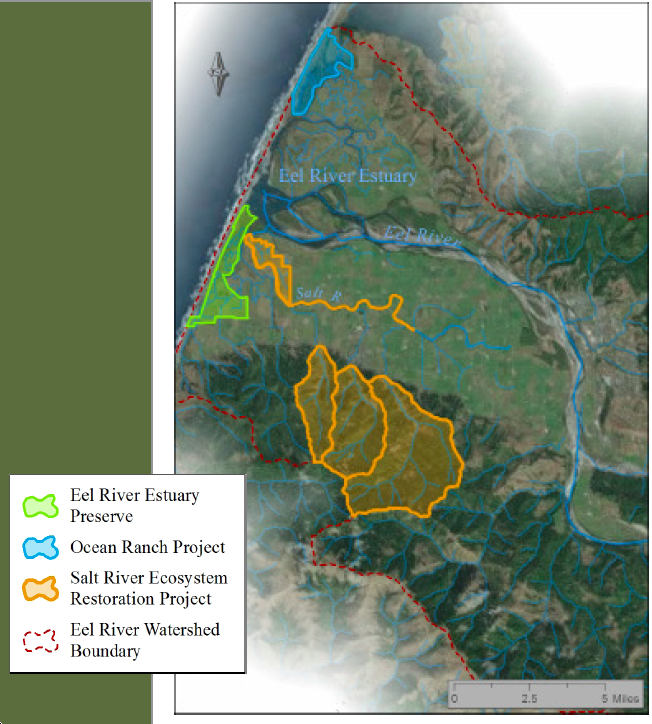

Still in its early phases, the Ocean Ranch project (pdf) is further north, just south of Humboldt Bay:

This area (blue in the map) was historically claimed for agricultural use, though it’s not currently being used as such. The project aims to improve the functioning of the tidal marsh, freshwater riparian areas and other habitats, which play host to Pacific salmon, migratory birds and other species.

The most ambitious of the three projects is the Salt River Ecosystem Restoration (pdf), which local landowners have been well aware of, given the massive amount of work that’s already gone into it over the past 30 years. Workers from a long list of project partners (see the pdf) have reconstructed a 330-acre tidal wetland, enlarged 2 1/2 miles of river channel and excavated more than three miles of internal slough networks.

When all is said and done, the price tag will be in the neighborhood of $13 million. The four main goals of the Salt River project include enhancing the tidal marsh, restoring the historic Salt River channel, managing upslope sediment and planning for future adaptive management.

Michael Bowen with the California Coastal Conservancy explained that, rather than constructing L.A.-style aqueducts, designers aimed for full ecosystem restoration, and wildlife biologists have already seen encouraging results.

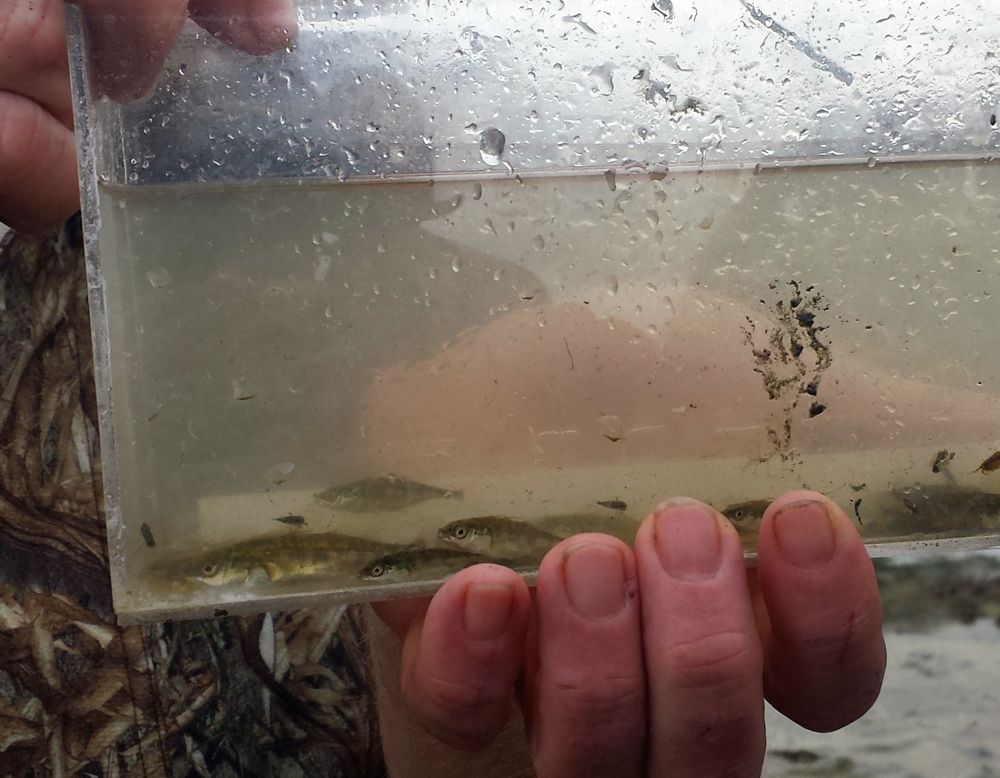

The SUVs pulled up on a dirt road along an excavated channel and the various stakeholders (along with a couple reporters) climbed out into the rain, which had just begun falling. Allan Renger, fish biologist with the California Department of Fish & Wildlife, explained how workers have been monitoring fish in the channel, and then offered a demonstration.

Two workers in fishing waders stretched a fine-mesh net across the width of the channel, with the bottom submerged underwater, and proceeded to walk upstream about 20 yards, dragging the net through the water. Then they lifted the netting up and slowly rolled the ends.

Finally they dumped the contents of the net into a clear plastic receptacle held by Renger, who walked back to the crowd, which had been watching from a slope beyond the mud puddles.

Renger held up the little bin to reveal fish inside — little sticklebacks and tidewater gobies.

Earlier in the day, Bowen said this happy outcome was far from assured. Before the design was complete, before the channels were widened and the slough networks excavated, scientists asked each other, “Will the fish figure it out? Will they know how to find their way back?”

They did. Still, there’s a long way to go before the estuary approaches the healthy ecosystem that it used to be. “These projects are not 50-yard dashes,” said former supervisor Jimmy Smith earlier in the day. “They’re marathons.”

Before restoration work, this channel was narrow enough to jump over.

Before restoration work, this channel was narrow enough to jump over.

CLICK TO MANAGE