Since October, Denise Mattson has been living with her husband and their baby at the Multiple Assistance Center, better known as “the MAC.” Located next to the Eureka Target and painted like a New Mexico stripmall, the 100-bed complex currently operates as a transitional housing facility with on-site programs aimed at helping the families who live there overcome the challenges of homelessness.

Mattson, who’s been in and out of several other programs, said she’s gotten the help she needs at the MAC. “We recently had a workshop about housing,” she said, “and they taught us about credit reports, how you can look and see what prevents us from getting housing — like if you have a water bill that needs to be paid off.”

She’s also taken life skills courses, learning about how to find employment, fill out housing applications and even reduce stress. And her husband has been attending a fathership group. Mattson is impressed.

“I feel very passionate,” she said. “This program works. It puts more people into housing. It’s the first [program] I’ve seen that actually works.”

Lately Mattson has been speaking out to the media and local officials, protesting against plans to repurpose the MAC. The facility is operated by the nonprofit Redwood Community Action Agency in partnership with the County of Humboldt and the City of Eureka, which owns the property. These agencies, led primarily by the county’s Department of Health and Human Services, recently decided to make some dramatic changes, repurposing the MAC building. Starting this summer the facility will no longer house or provide services to families; instead it will be used as an intake facility geared toward helping the county’s chronically homeless individual men.

Families living at the MAC, who in recent years have been given as long as 18 months to get their lives back on track before moving out, were notified they’d have to leave no later than June 30. The county and RCAA are working to get each family placed into more permanent housing, with funding for support services following them into the community. But Mattson said she’s scared about the future.

“I have no idea what will happen,” she said. She feels that the MAC is “the only place for families to go in Humboldt County.”

Residents aren’t the only ones worried. Current and former MAC staffers, along with various community members, have voiced concerns about the upcoming transition, which marks a major shift in the way Humboldt County addresses homelessness.

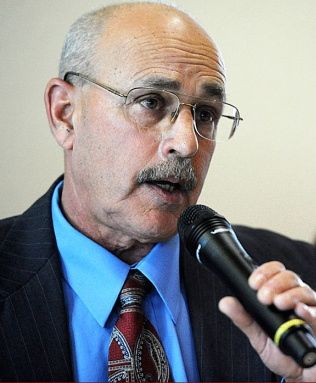

Much of the ire has been directed at Phillip Crandall (pictured at right), director of the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services. Crandall recently sat down for an interview in the conference room on the fifth floor of the Professional Building, on the corner of Fifth and F streets in Eureka.

Much of the ire has been directed at Phillip Crandall (pictured at right), director of the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services. Crandall recently sat down for an interview in the conference room on the fifth floor of the Professional Building, on the corner of Fifth and F streets in Eureka.

“I just want to reassure everyone that the county is not in the business of increasing homelessness,” he said, “and we’re certainly not going to be throwing children and families out into the streets. … We would not close the MAC if we didn’t have an alternative plan for the families.”

That alternative plan focuses on getting homeless people — both individuals and families — placed into permanent housing as quickly as possible, as opposed to the transitional housing approach embodied by the MAC.

Crandall and other officials say this shift in approach was motivated by two main factors: evidence and funding. In recent years, government agencies that deal with chronic homelessness — particularly the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) — have themselves shifted gears, putting less focus on transitional programs like the MAC and more on “housing first” approaches, including rapid re-housing and permanent supportive housing.

Ed Cabrera, a San Francisco-based spokesman for HUD, said that the old school model for addressing homelessness focused on “housing the most housing ready.” In other words, the people who could show up for meetings and fill out applications were most likely to receive aid. But HUD is now encouraging local communities to take more strategic approaches in hopes of reaching “the most visible, the most vulnerable — the chronically homeless,” Cabrera said.

In Eureka these days the most visible homeless people are usually men, often with addiction and/or mental health problems. This is the community that RCAA and the county hope to serve better by turning the MAC building into an intake facility where these men can stay for roughly 30 to 60 days while a long-term plan is developed for their housing and services.

Eureka has arguably been the ugliest and most volatile battleground in the fight to end homelessness locally, with regular raids on homeless camps, roundabout enforcement efforts like the shopping cart ordinance and escalating community vitriol, which was partially (and illogically) sparked by the New Year’s Day murder of Father Eric Freed.

With public outcry over homelessness reaching a fever pitch, the city commissioned a homelessness policy paper from a Sacramento consulting firm called Focus Strategies. That paper, released last fall, encouraged a new approach.

“Focus Strategies strongly advises the City of Eureka not to pursue approaches directed at better managing the existing problems, such as by increasing the frequency of police sweeps or creating a legalized camping area or ‘tent city,’” the paper said. “All available evidence shows that providing homeless people with housing, without making participation in other services a pre-condition, is the most effective way to reduce homelessness.”

This jibes with HUD’s shifting priorities and further motivated county officials to change their approach. Could a repurposed MAC get Eureka’s chronically homeless off the streets?

The latest messaging and data suggest so. According to the federal government’s Interagency Council on Homelessness, “housing first” programs “allow people with one or more serious disabling conditions to stabilize their housing and address underlying conditions that often have gone untreated for many years.”

The philosophy goes all the way to the top of U.S. government. President Obama helped codify the strategic shift during his first year in office by signing the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act of 2009. And when federal agencies adjust positions, nonprofit grant funders tend to follow suit. Sure enough, the shift in strategies has been trickling down to local communities around the country.

Image from RCAA’s Facebook page.

Image from RCAA’s Facebook page.

Val Martinez is the executive director of the Redwood Community Action Agency, the nonprofit that operates the MAC. “When we first heard that HUD was shifting focus to rapid rehousing we were concerned,” she said. In recent years HUD has provided only about eight percent of RCAA’s annual budget to run the MAC. (The 2015 budget, which was finalized before the changes to the MAC were decided, was $1,351,959, with a HUD grant of $104,147, or 7.7 percent, awarded just last month. Martinez said RCAA will now ask HUD for permission to redirect the grant to reflect the new mission.) But RCAA’s program director spoke with various other funders that supply the remainder of the MAC’s funding and they said they’d be following HUD’s lead in moving away from transitional housing models, Martinez recalled.

To hear Martinez and county officials tell it, the MAC was all but forced to change because its approach is becoming obsolete.

But longtime advocates of the MAC say that it’s too unique and valuable a program to be mothballed. Amy Whitlatch is a former employee of RCAA who worked at the MAC from October 2012 through July 2013, including a five-month stint as its acting director.

“I believe in the MAC; I love the MAC,” Whitlatch said. “I can’t tell you how meaningful it is to the people who live there. … The changes you see in families, in children, it’s just phenomenal.”

The MAC opened its doors in 2005 following 13 years of planning, delays and objections from local business owners and neighbors, who worried about panhandling, crime, graffiti and litter. It was originally intended to serve both families and individuals but after encountering funding troubles it was repurposed in 2008 to serve only families.

While Whitlatch understands the latest shift toward “housing first,” she argues that the transitional housing model offered at the MAC is necessary in rural areas like ours, where low-income housing is limited, wages are relatively low and social services are overburdened with demand.

Martinez, RCAA’s executive director, also sounded regretful about the elimination of this transitional housing program in favor of rapid rehousing. “If I could talk to HUD I‘d say there needs to be some blend [between the two], but until they make me queen of the world I have to follow their lead.”

But the truth is that HUD does still fund programs like the MAC. Cabrera, the HUD spokesman, said transitional housing programs are a necessary component in each community’s “Continuum of Care,” meaning its organized approach to ending homelessness.

“HUD does not advocate the wholesale removal of one type of resource in a community for another,” Cabrera said. “We see that as being short-sighted and not taking into account the specific needs of communities.”

Ultimately, Cabrera said, HUD wants local agencies to be more strategic and have thoughtful conversations about the efficacy of each individual program. “Research shows that this limited resource — transitional housing — is often not being targeted appropriately,” he said. In other words, the people most in need have tended to fall through the cracks.

But Whitlatch feels that the families living at the MAC really do need its services. “The MAC becomes the place where they make a stand to change their life,” she said. Whitlatch has personally watched as families worked to repair their credit, get counseling, earn certificates at College of the Redwoods and find jobs. She also saw children get much-needed one-on-one attention including services from mental health programs geared specifically for kids. “A lot of children will all of a sudden start behaving better [and] doing better in school,” she said. “The case management there [at the MAC] is something you can’t replace. To have someone holding your hand, helping you follow through, it becomes more manageable to change your life.”

Another benefit: When parents have their kids removed by Child Welfare Services, the MAC has allowed families to get reunited more quickly because case workers know the site is safe. Often, more than half the residents at the MAC are children. Whitlatch believes that the consequences of closing it to families will be dire. “To lose that [the MAC] means more children will be homeless,” she said.

But county officials insist that the “wraparound” support services offered at the MAC will follow these families as they move out into the community. The funding for those services comes largely from CalWORKs, the state welfare program offering cash aid and services to eligible families. So the various workshops and classes that MAC resident Denise Mattson and her family have enjoyed onsite will be offered elsewhere, at community centers, churches, nonprofit offices and the like.

Cabrera, the HUD spokesman, said this latter model has proved effective. “We’ve found there’s no service that can be provided in transitional housing that can’t be offered once a person is permanently housed,” he said.

Crandall argues that offering services on-site at the MAC may actually be counterproductive. “Are we fostering independence?” he asked. “Or are we fostering dependence on a system that doesn’t exist out there in the real world?” Children’s playgroups offered at the MAC, for example, are also offered through First Five programs throughout the community, Crandall pointed out. And when parents access those services at a church or community centers it connects them with people who aren’t in the same situation, potentially expanding their social support system.

“It worries me when people say, ‘It’s either this program or else I’m in an abyss,’” Crandall said. “That’s almost an example of the dependence that’s being perhaps taught inadvertently as a part of this program.”

He compared this transition to the evolution of strategies with child welfare services and orphanages. Children used to be placed in group homes and orphanages until research showed that kids do better when placed in community-based family living environments, with services brought into the homes.

“Closing orphanages doesn’t mean you don’t care about families,” Crandall said. “The lessons learned there are the same: We want to normalize the living environment and move toward fostering problem-solving and independent judgment.”

Barbara LaHaie, the assistant director of programs at the county Department of Health and Human Services, said there’s a team working with each family currently living at the MAC to identify their particular needs and barriers to finding permanent housing.

Crandall expressed confidence in this process. “We’ll meet with each and every one of those families, and unless they’re absolutely against engaging with us we’ll work with them to solve their housing issues,” he said.

But Whitlatch and other MAC defenders — some of whom contacted the Outpost but declined to go on the record — worry that there’s simply not enough affordable housing in the area. The wait list for Section 8 housing, the HUD program offering vouchers to subsidize rents, is past capacity in Humboldt County and has been closed to new applications for two years or more, according to Eureka Housing Authority Executive Director Wesley Weir. There are currently more than 400 people on the list, Weir said, adding that his agency may reopen it soon. Regardless, that’s a long wait list.

Yet Crandall argues that there’s a misperception in the community about affordable housing.

“People are stuck with [the idea] that there is nothing. I don’t believe that at all,” he said. “I believe that there’s a lot of available housing stock out there. It’s just not coordinated in a way that we can access it effectively.”

In an effort to remedy that, Crandall’s office and the RCAA are working to improve coordination between the 40-or-so agencies that comprise the Humboldt Housing and Homeless Coalition (HHHC), which includes service providers, government agencies, faith-based organizations and community members. The effort will also entail trying to reduce the stigma of mental illness so that landlords are more comfortable renting to those in need. The county’s Department of Health and Human Services has already begun collaborating with officers from the Eureka Police Department to form the Mobile Intervention and Services Team (MIST) to serve homeless people with severe mental illness.

The MIST team in action. Photo courtesy Humboldt County DHHS.

The MIST team in action. Photo courtesy Humboldt County DHHS.

Whitlatch said these new developments sound great. “The rapid rehousing they’re proposing is fantastic, and it’s a much needed program for Humboldt County,” she said. What Whitlatch and others wonder is why the county can’t provide families the same rapid rehousing services without booting them out. “The MAC is such a special place,” Whitlatch said.

Crandall said this new approach is exactly what HUD suggests — a thoughtful and strategic experiment based on the best research available. “It’s an experiment in that we don’t know everything yet,” he said. “The first thing to acknowledge is that we don’t know. And that should not cause a state of paralysis.”

When volunteers set out last month for the biannual homeless count in the county they certainly found many people who have fallen through the cracks of care and services provided here. (Though contrary to the oft-repeated local theory that these services attract homeless people to Humboldt County, the data show that there are downward trends in access to those services, which proves to Crandall at least that they are working.)

But will grasping to help those who are currently homeless cause families to suffer the same fate?

“We’re taking risks,” Crandall acknowledged. “But they’re risks based on what the literature tells us is probably our best bet.”

Time will tell if that bet pays off.

CLICK TO MANAGE