Quick question for Eureka residents: Do you know which ward you live in?

Follow-up: Did you even know the city is divided into wards?

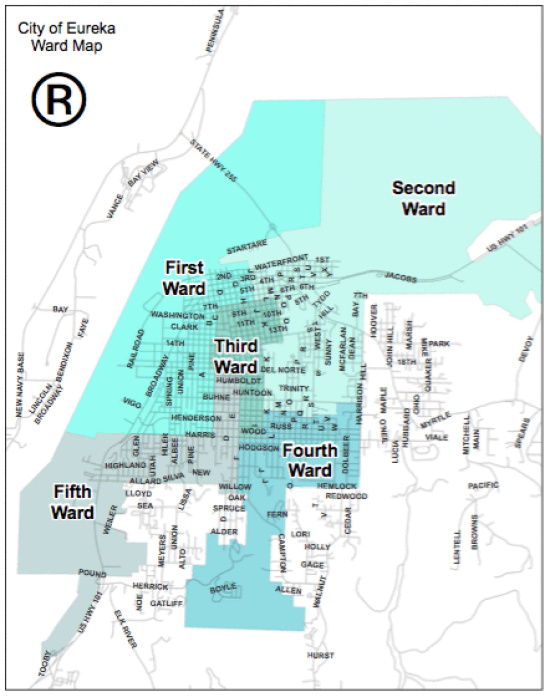

If not, don’t sweat it. Under the city’s nonsensical electoral system, unless you’re running for a seat on the City Council there’s not much reason to know or care which ward you’re in. (You can check this map, though, if you’re curious.)

The “skull-crushingly dumb” system currently employed in Eureka works like this: The city is geographically divided into five wards, with a City Council made up of one representative per ward. For example, Eureka’s First Ward, which encompasses the West Side and Old Town, is represented by Marian Brady, who also lives in that ward. She has to, or else she wouldn’t be eligible for that seat. Councilmember Natalie Arroyo, meanwhile, lives in and represents the Fifth Ward, including Eureka’s south side and Henderson Center.

Makes sense so far, right? The goofy twist is that that the entire city gets to elect the representative from all five wards. As Outpost Editor Hank Sims noted two-and-a-half years ago, Eureka is utilizing a mishmash of two different systems, which are almost never mishmashed. Cities and counties either hold at-large elections, wherein each councilmember represents the entire city and the entire city votes for him/her, or they use a so-called “true ward system,” wherein each councilmember represents the ward in which she lives, and she’s elected only by the voters in that ward.

The city’s current system has forced many an aspiring candidate to pick up and move to a new ward in search of an open seat, prompting the predictable cries of, “Carpetbagger!” More importantly, this mixed-up method makes it more challenging and more expensive to run for office by forcing candidates to campaign citywide, and there’s no evidence that it leads to better governance.

Tonight, the Eureka City Council can empower the city’s voters to fix this situation. An item on tonight’s agenda would, if approved, place an initiative on November’s general election ballot, letting voters decide if the city should amend its charter to create a true ward system.

Opponents of the true ward system say it encourages elected representatives to engage in Chicago-style “ward politics,” trading favors for votes and focusing on their own constituents at the expense of the common good. But the fact is that Eureka’s wards aren’t politically or demographically distinct enough to warrant such fears. Residents in each ward have their own neighborhood concerns, sure, but our priorities for the city itself — addressing crime, homelessness, jobs, etc. — are fairly uniform.

Yet city staff’s motives are not idealistic; they’re fiscal: They don’t want to get sued. City Attorney Cyndy Day-Wilson warns the council in her agenda summary of an upswing in legal challenges to at-large voting systems across the state. These suits often allege that at-large voting violates the California Voting Rights Act (CVRA) by disempowering minority populations. In cities where voting is polarized along racial lines, these suits argue, at-large voting can make it harder for minority candidates to win elections by diluting the minority vote.

“[T]he City does not currently know if there has been or is racially polarized voting in Eureka,” Day-Wilson notes, but she concludes that it’s not worth the risk. In researching this situation she found no city that successfully defended a CVRA suit without having to pay attorneys’ fees. And cities that fight these suits just wind up paying more money.

Linda Atkins, the city’s Second Ward representative, echoed this argument on Facebook:

She has also made the case that a true ward system would be easier on candidates. “You can knock on everybody’s door in a ward; you can’t knock on everybody’s door in the city,” she told the Times-Standard.

She’s right on both counts. But the best reason to change Eureka’s electoral process to a true ward system is even simpler: It’s a better method of representative democracy.

CLICK TO MANAGE