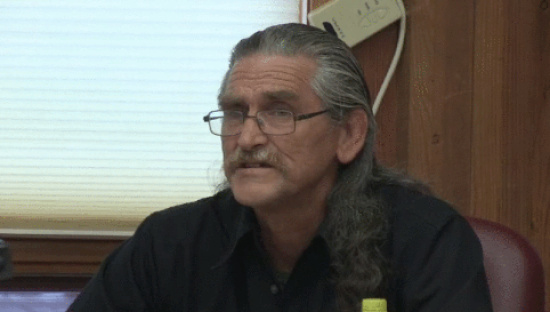

Dunlap | Screen shot from a Yurok tribal chair candidates’ forum video.

James Everett Dunlap says there’s no way to explain what he was thinking on the Friday afternoon in 1988 when he fatally stabbed his infant daughter with a buck knife as she lay in her crib.

“There’s no understanding the kind of thoughts that goes through somebody’s mind like that,” he told the Outpost in a phone conversation this morning. “There’s no possible way for an individual to understand what goes through somebody’s mind who’s psychotic. There’s no explanation. Because it’s not rational. Not conventional. No one’s going to be able to understand it.”

As reported earlier this week, Dunlap resigned as chairman of the Yurok Tribe on Tuesday morning after the tribal council learned about this heinous crime from his past. Old news reports recently surfaced on social media revealing the murder and other crimes. Law enforcement in San Mateo, where the baby killing occurred, said at the time that Dunlap was likely under the influence of methamphetamines when he killed his daughter, a crime he allegedly committed in an attempt “to set her free for God.”

The North Coast Journal reported that a jury convicted Dunlap in 1990 of second degree murder, but because he was deemed to be insane at the time of the crime he avoided prison and was instead sent to Atascadero State Hospital, a psychiatric facility. He was released in 1993 and legally found “restored to sanity” two years later, the NCJ reports.

In response to a request for comment, Dunlap yesterday sent the Outpost a message on Facebook suggesting he’d been unjustly targeted for threatening the political status quo in tribal government. Someone, he said, was “sensationalizing” and exploiting his “personal family tragedy” for “individual political purposes.” This “digging up dirt,” he continued, was an “orchestrated distraction.” He also claimed that he had fully disclosed his criminal past to the tribal election board. (Dunlap evidently sent a nearly identical message to the Times-Standard.)

Calls and emails to the Yurok Tribe this week have not been returned.

When the Outpost reached Dunlap by phone this morning he sounded despondent, and his listless demeanor continued throughout the half-hour conversation. He repeated his assertion that he gave full disclosure of his criminal record to the tribe’s election committee, saying he sent a letter with that information three years ago, when he first ran for office.

“You’re required when you run for office to make [a] full disclosure,” he said. “So when they ran my background, my criminal history came up, and they asked me to submit a letter explaining, which I did. I said I have no problem with that. I know it’s pretty extensive, and pretty severe.”

Specifically, the tribe’s elections ordinance forbids any candidate from running if he or she has been convicted in the previous 10 years of any violent felony or crime of “moral turpitude,” such as fraud, drug charges or embezzlement. Of course, the child murder took place nearly 30 years ago, and Dunlap was ultimately found not guilty by reason of insanity. Did he disclose that information?

“Yeah,” he said. “I disclosed that in 1988 I was charged with second degree murder and was found not guilty by reason of insanity.” What he didn’t tell officials, Dunlap acknowledged later in the conversation, were “the gory details.” Still, he disclosed a 1986 felony assault conviction from Washington state, he said, and the elections committee cleared him as a viable candidate.

“They allowed me to run,” he said. Dunlap lost the chairman election that year by just two votes, he said, but he won this year, landing the seat four months ago.

But it all fell apart this week, and Dunlap sounds like he’s still trying to figure out how and why.

“From what I understand, I guess Monday night somebody posted stuff up on Facebook,” he said. “I think, uh, Tuesday morning we had a council work session scheduled. They [the council] met before the session. At 1 o’clock I went to the work session, and they asked for my resignation.”

The council had learned the specifics of his 1988 crime, Dunlap said, though he suggested that it’s their own fault for not bothering to look into it earlier. The details, he said, were on file in the tribal attorneys’ office. “They had access to it, whether or not they went to look at it.”

Does Dunlap really believe that his past was dredged up for someone else’s political gain?

“I’m not a very credible person right now,” he said in response. But then he pressed on. “Ask yourself why, what’s the benefit of getting this out, you know? Is it to enlighten people? Is it to make their life better?”

Asked if voters and the tribe at large had a right to know about the incident, Dunlap was silent for a moment before responding quietly: “Um … does it impede my ability to do a job?”

We pressed him to answer that himself. Does he find the crime irrelevant now? “Yeah, at this point, yeah,” he said hesitantly.

A few moments later he elaborated. “It just opens the door for a very big conversation, because at what point is it pertinent information? At what point is your past acceptable? I’m just saying in the larger picture. I know my [past] is so severe and so horrifyingly shocking that it would not be the best scenario to really discuss that in the larger picture … .” He trailed off, the thought unfinished.

Among the documents circulated in recent days on social media is a 1986 affidavit from the State of Washington concerning an armed standoff Dunlap had that year with law enforcement officers in Whatcom County. The document says Dunlap fled from state troopers in a car and, over the course of a 2 1/2-hour armed standoff, shot a hole in the car’s windshield and shot his gun into the air in the vicinity of a SWAT team and tactical sheriff’s unit. Dunlap was finally disabled when an officer shot him in the buttock with a gas canister.

The report also mentions an “extensive record of arrests in California involving ingestion of drugs and illegal conduct related to his consumption … [plus] related felony convictions and a background involving assaults and deadly weapons.”

The Outpost contacted the Humboldt County Probation Department and District Attorney’s Office, along with the San Mateo County District Attorney’s Office in hopes of tracking down a full account of Dunlap’s rap sheet. None of the agencies were able to provide that information without either an open case or case number. Crimes in the 1980s predate the Probation Department’s computer records.

Dunlap admitted that he was convicted of felony assault with a deadly weapon for the Washington incident, but he repeatedly denied having been convicted of any other felonies. Why would the State of Washington claim otherwise? “Yeah, I don’t know why,” Dunlap said.

Asked if he thinks the tribal council’s request for him to resign was unfair he said simply, “Life is not fair. No one complains when you hit the lottery, so why should you complain when less pleasurable things happen? It’s just life. It is what it is.”

If it’s impossible to understand how a man could kill his own baby daughter, it’s not much easier to imagine what it’s like living with the knowledge that you’d done so. We asked Dunlap if it’s been difficult. Again, he was quiet for a few moments before answering.

“Um, yeah,” he said finally. ”[It took] years and years to learn to be able to live with myself. In order to move on. Now I have a deep passion trying to deal with people on drugs, trying to get them off because I know the consequences firsthand, the consequences from coming from broken homes … .”

His past, he said, has given him a passion for developing and implementing social services in an effort to “break the cycle” that leads to addiction and dysfunction. That’s what he had hoped to do as the tribal chairman, he said. What are his plans now?

“Um, I’ve got a broken gate that needs to be fixed,” he said. “I’ve got some facing boards on the side of the house where the condensation rolls up the bathroom window that’s gotta be fixed.” He’ll probably go back to his professional flooring business, he said, installing floors in hotels and apartment complexes throughout the western U.S..

Will he continue living on tribal land?

“Undecided,” he said sullenly. “The river is still who I am. It’s what brought me home. I’m still part of the river.”

CLICK TO MANAGE