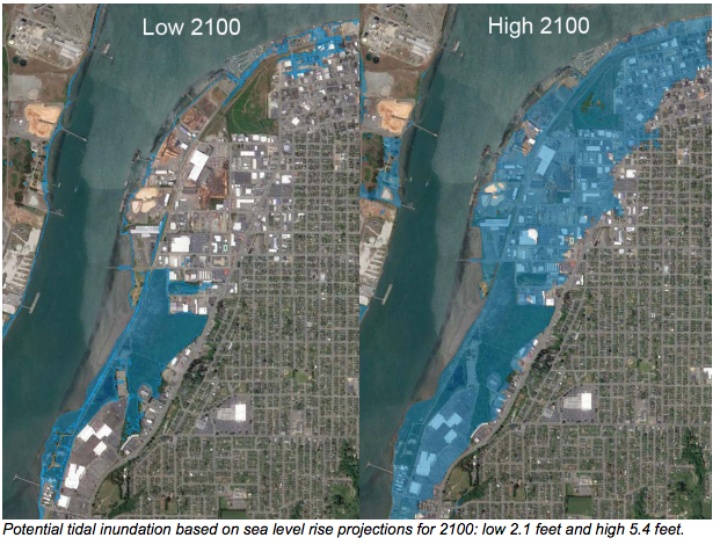

The images are dramatic, showing some of Eureka’s most important areas completely submerged in water. The Bayshore Mall, Costco, Schmidbauer Lumber, even parts of Old Town and Highway 101 would lie beneath the surface of the ocean according to the worst-case-scenario projections for sea level rise and tectonic subsidence by the year 2100 in a new draft report prepared for the City of Eureka.

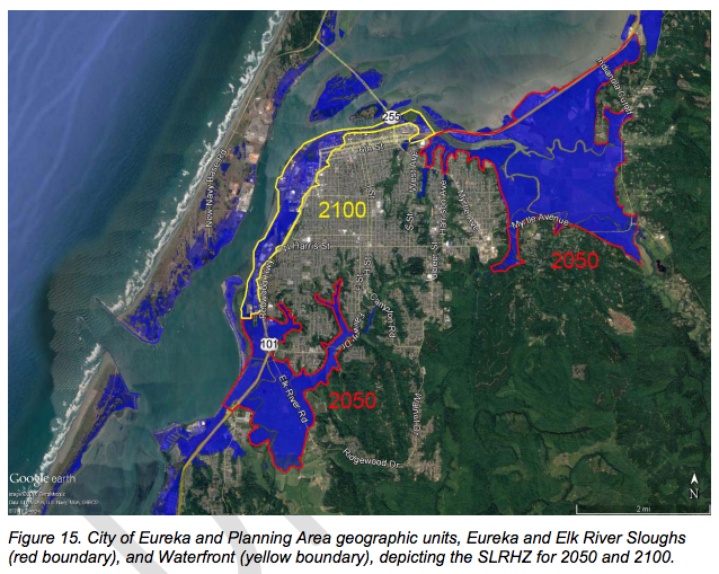

A broader image shows even more impacts, with the Eureka Municipal Golf Course, Murray Field Airport, Jacobs Avenue and much of the 101 safety corridor underwater:

Earlier this week the Eureka City Council got a look at this new draft report and heard from Community Development Director Rob Holmlund, who explained to the council why he thinks that, despite these dramatic images and dire projections, the city should disregard policy recommendations from the California Coastal Commission as it finishes updating its general plan.

Last year the Coastal Commission issued a Sea Level Policy Guidance document, in which it advises cities and counties to start seriously planning for continued rising seas along the state’s coastline. Specifically, the agency suggests that local jurisdictions base their planning policies on the worst-case-scenario projections for the rising oceans, limiting or denying development in sea level rise hazard zones. Anywhere the sea is projected to reach by the year 2100 should be off limits to new development, according to the agency.

“And I fundamentally disagree with the Coastal Commission’s recommendations,” Holmlund said in Tuesday’s council meeting. “I want to use something a lot less extreme.”

The tension, here, lies between the scientific projections and the city’s desire to “maximize development for the benefit of the community,” as the recently commissioned report notes. It elaborates: “Several of the Coastal Commission’s policy guidance principles for adaptation planning have the potential to limit development and therefore, if adopted by the City, may limit attainment of the City’s land use goal of maximizing development, at least in SLRHZs [sea level rise hazard zones].”

If, for example, Costco wanted to expand, or Rob Arkley finally moved to develop his Balloon Track property, those projects would have to be denied if the city were to follow the Coastal Commission’s guidelines.

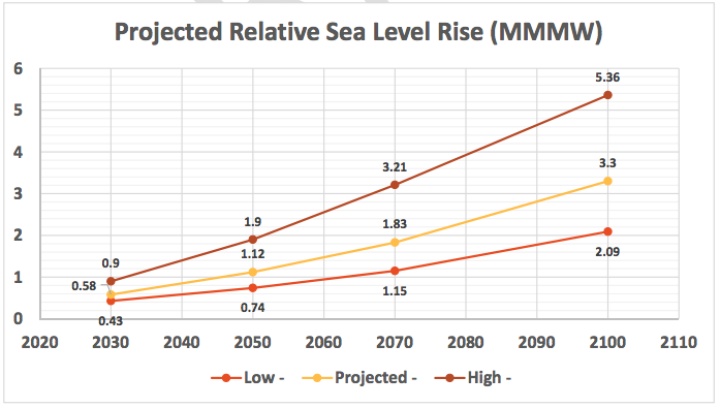

Holmlund noted several reasons for disregarding that guidance. He pointed out that the draft report, prepared by Aldaron Laird of Trinity Associates, shows a dramatic difference between the low projection and the high projection for sea level rise, a gap that widens over time:

Note: MMMW stands for “mean monthly maximum water.”

The worst case scenario in Eureka predicts that the Pacific will have risen more than five feet by the year 2100 while the low projection shows it rising only about two feet.

Holmlund suggested that, rather than basing policies contained in the general plan on the 2100 projections, the city should instead aim for the 2050 projections and plan for roughly two feet of sea level rise. That mark is roughly the same as the low-level projection for 2100, Holmlund noted, and 2050 is a full decade beyond the planning horizon for the upcoming general plan update.

Holmlund also questioned the reliability of the projections themselves and the resulting maps. He compared them unfavorably to the hundred-year floodplain maps produced by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), maps which are certified by federal agencies. These sea level rise maps, in contrast, are relatively new (“first generation,” as he called them) and haven’t been certified by the feds.

Lastly, Holmlund noted that Humboldt Bay’s current footprint and channels have remained where they are since the 1890s when a property owner put up a series of berms, “reclaiming” saltwater marshland roughly 100 years before the Coastal Commission was created. Local agencies have maintained the levies ever since and will continue to do so. “You don’t even need to believe in sea level rise to believe that we need to maintain hundred-year-old levies,” Holmlund said.

While Holmlund is encouraging the council to be flexible with the Coastal Commission’s guidelines, environmental activists say those guidelines should be taken seriously.

Jennifer Savage, California policy manager for the nonprofit Surfrider Foundation (and, disclosure, a friend of this reporter), said California is already behind when it comes to planning for sea level rise.

“The Coastal Commission staff is on the front lines of this issue and understands that short-term planning is what’s made us vulnerable and sensibly asks jurisdictions to protect their communities going into the future,” Savage said. “A city as at risk as Eureka should take this especially seriously – we’re facing future environmental and economic consequences that can’t be undone if we fail to properly plan in the here-and-now.”

In a phone conversation Friday afternoon Holmlund said he agrees with that statement 100 percent. “That’s why Eureka will make sure that those blue maps will never occur,” he said. Comparing the risk of rising seas to that posed by a steamroller approaching from 100 miles away, Holmlund said the city and other government agencies will have plenty of time to forestal danger.

In his presentation earlier this week he mentioned that Eureka recently joined with the county to apply for a $500 million $500,000 grant through Caltrans for a pilot study to analyze the best ways to protect infrastructure from sea level rise.

“This isn’t to say that Eureka denies climate change or is not taking it seriously,” Holmlund said in today’s phone interview. He just thinks the Coastal Commission’s recommendations are unnecessarily extreme. “It is premature and irresponsible to utilize the worst-case scenario for the deep future to restrict development,” he said.

The City Council will decide at a future meeting whether it agrees with him.

CLICK TO MANAGE