I

cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag. I know

that I am a black man in a white world.

— Jackie Robinson in his 1972 autobiography, I Never Had It Made.

###

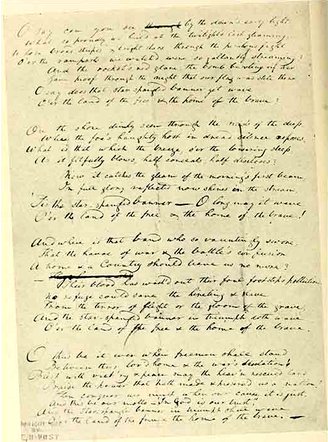

Original manuscript of Key’s Star-Spangled Banner (Wikimedia Commons, Maryland Historical Society)

I

know essentially nothing about baseball, football, or any other kind

of ball; to say I’m illiterate in sports is like saying water’s

wet. So I barely registered last week’s headlines about

Not-My-President yelling abuse at football players who refused to

stand for the National Anthem. I knew, of course, that the anthem was

called The Star-Spangled Banner and that a lawyer named

Francis Scott Key had written it after witnessing the bombardment of

Fort McHenry during the War of 1812. (If for no other reason, because

this was part of the U.S. Citizenship Test when I took it about 20

years ago.) I think I can sing it, even—the first verse, that is.

Nice tune, so much better than the dirge-sounding “God Save the

King/Queen” anthem of my home country.

“Read the rest of the song,” I was advised when I asked someone about the whole “taking the knee” controversy. “It’s racist.” Sorry if you, dear reader, know all this. It was news to me. Key’s original third verse ends:

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Which I take to mean, I’m sure you’ll correct me if I’m wrong, that Key was taking great pleasure in imagining the impending fate of black slaves who had signed up to the British side. A more racist sentiment would be hard to find, even back then.

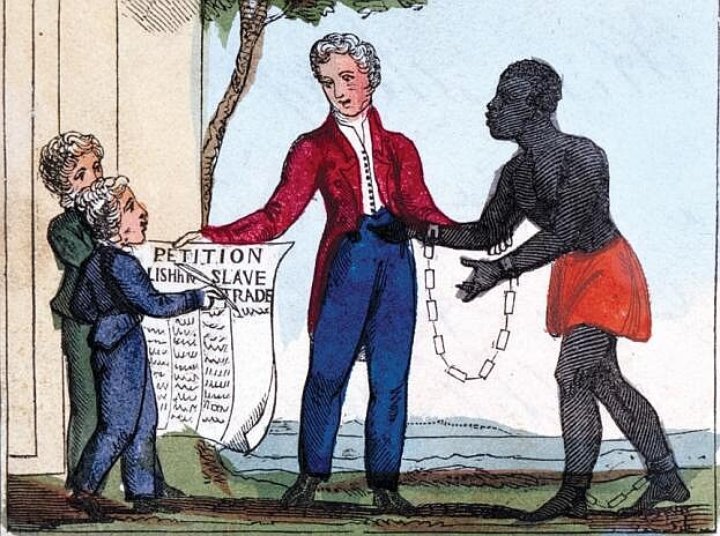

Illustration from the book The Black Man’s Lament by Amelia Opie. (London, 1826)

Britain at the time of the Revolutionary War was kinda-sorta anti-slavery. Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act in 1807, outlawing the trade, but not slavery itself. That didn’t happen until 1833 with the Slavery Abolition Act. But the British forces, led by Admiral Sir George Cockburn of the Royal Navy, had every reason to accept blacks into their ranks—who better to fight the colonialists than escaped slaves? Indeed Cockburn’s orders read, “Let the landings you make be more for the protection of the desertion of the Black Population than with a view to any other advantage…The great point to be attained is the cordial Support of the Black population.” And so it was. During the two-year campaign, he rescued some 6,000 slaves, many of whom swapped their rags for red coats.

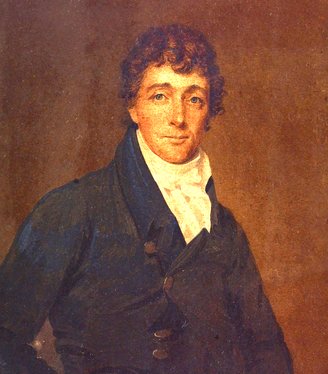

Francis Scott Key as painted by Joseph Wood in 1825 (Public domain)

In

any case, Francis Scott Key, a rich slave-holding lawyer who once

wrote that blacks were “a distinct and inferior race of people,

which all experience proves to be the greatest evil that afflicts a

community” is an unlikely hero of the republic. According to an

article in the September 2014 Harper’s

Magazine

by Andrew Cockburn (who claims the good admiral as a relative), Key

“went on to a long career as a powerful crony of President Andrew

Jackson, a mentor to Chief Justice Roger Taney of Dred Scott fame,

and, as district attorney for the capital, an energetic prosecutor of

abolitionists.”

So yeah, even knowing nothing about sports, I can see why black players would have trouble standing for our National Anthem. Maybe we all should.

###

Barry Evans gave the best years of his life to civil engineering, and what thanks did he get? In his dotage, he travels, kayaks, meditates and writes for the Journal and the Humboldt Historian. He sucks at 8 Ball. Buy his Field Notes anthologies at any local bookstore. Please.

CLICK TO MANAGE