“[Junípero

Serra] believed that the death of an unconverted heathen was tragic,

while the death of a baptized convert was a cause for joy.”

— (Into the West: The Story of its People, Walter Nugent)

###

Stanford University is currently going through its own “McKinley Moment” in dealing with the legacy of the Franciscan monk Fr. Junípero Serra. Last week, university authorities announced the compromise achieved after years of debate: Fr. Junípero Serra’s name is to be removed from the main mall and two buildings on the campus, while remaining on other features, including Serra Street.

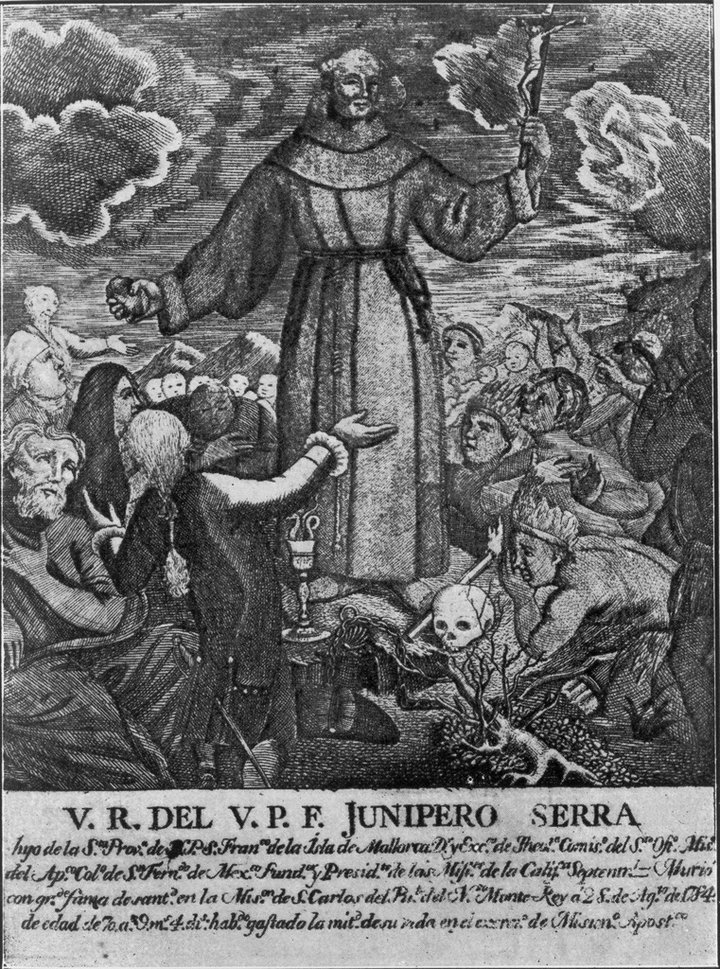

Fr. Junípero Serra (1713-1784) preaching, cross in one hand, stone in the other. (Francisco Palou, 1787. Public domain.)

If you’ve been following Arcata’s “What to do about William McKinley’s statue?” debate, you’ll be familiar with the issues. In a nutshell: do we judge historical figures by the standards of their own time or by our own? Was McKinley an imperialist empire-builder whose legacy led to dictatorships in Cuba and the Philippines? Or an enlightened leader working in the best interests of a country still struggling, decades later, to overcome the aftermath of the Civil War?

Junípero Serra’s case is more complex than McKinley’s, complicated as it is by the overtones of unabashed certainty in the tenets of the One True Faith. Spanish missionaries in the New World were saving souls for eternity, not trying to improve their living conditions in this world. When Bishop Landa, in an unspeakable act of cultural genocide, torched dozens of Mayan codexes—books—along with thousands of carved figurines, in Mani, near Merida, in 1562, he no doubt rejoiced at the righteousness of destroying heathen idols. (Just three Mayan codexes, plus fragments of a fourth survive today.)

Bishop Landa’s “auto de fe de Mani” which destroyed much of Mayan culture in 1562. Mural in the Palacio de Gobierno, Merida, Mexico. (Barry Evans)

Similarly, Junípero Serra had no compunction in employing what the Stanford authorities describe as “harmful and violent impacts of the mission system on Native Americans, including through forced labor, forced living arrangements and corporal punishment.” In his defense, he also intervened on behalf of native people and championed rights that the Spanish authorities and military chose to ignore. His work took him first to Jalpa, in Mexico’s Sierra Gorda; later to Laredo in Baja California; and later yet in “Alta California,” where he founded nine missions between San Diego and San Francisco.

Fr. Serra commissioned five churches in Mexico’s Sierra Gorda, the facades of which are flamboyantly decorated with a mix of Christian and Paman Indian iconography. (Barry Evans)

Our understanding of the past is inevitably shaped by our understanding of the present. We can’t see the world through the eyes of McKinley, Landa or Serra; we can only strive to understand the actions and words (most of Serra’s copious writings and letters have survived) by trying to suspend our own contemporary biases.

So, Junípero Serra: saint or sinner? No question according to Pope Francis, who canonized him three years ago during his visit to the US. Next time you’re driving up “Junípero Serra Freeway” (I-280), pause at the rest area near the Half Moon Bay turn-off, take a good look at the massive statue of the saint overlooking “his” freeway, and decide for yourself.

CLICK TO MANAGE