The Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office makes a practice of hiding or deleting social media comments critical of its agency, according to information obtained by the Outpost through a public records request.

When a comment is hidden on a business or organization page on Facebook, it is only viewable by the poster and their friends, essentially censoring their comments from the general public and possibly violating their First Amendment rights.

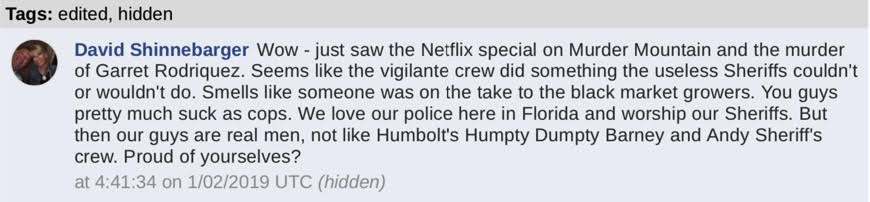

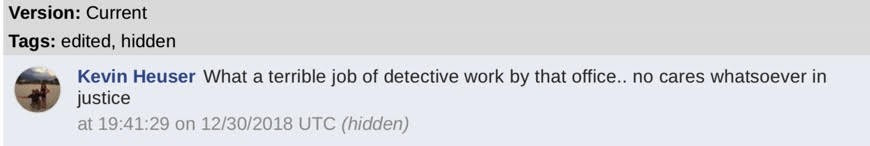

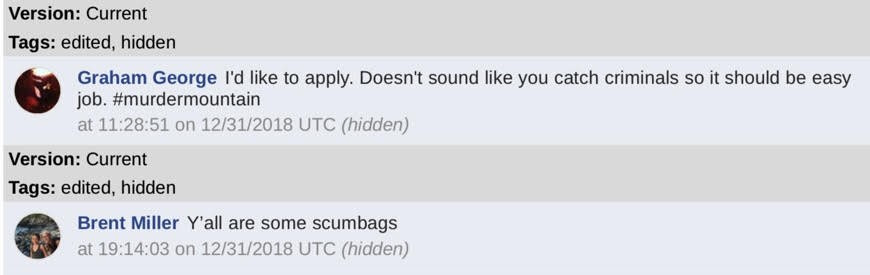

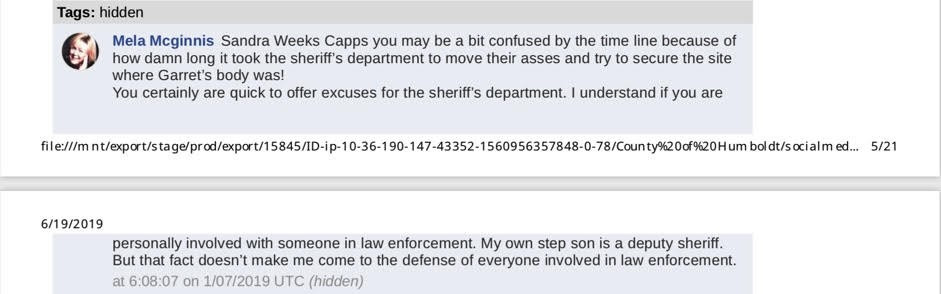

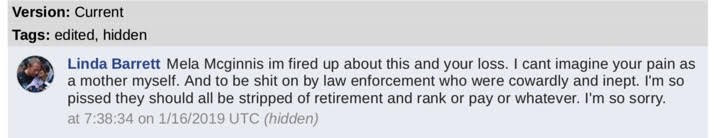

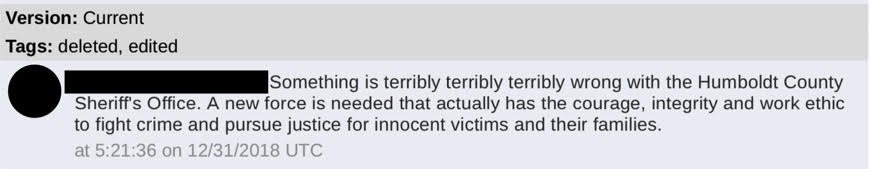

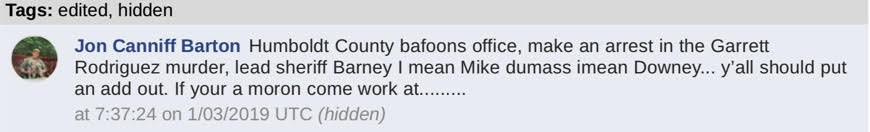

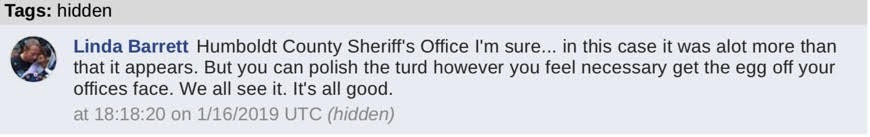

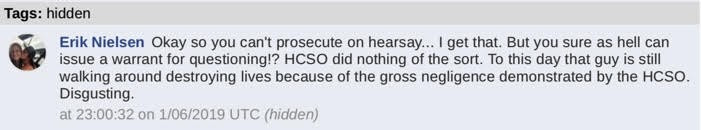

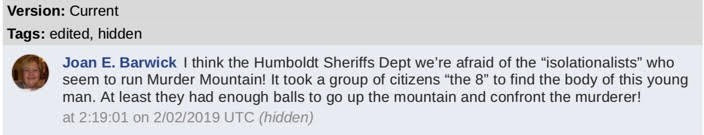

Some of the hidden comments pertaining to the Garret Rodriguez case featured on the Netflix series Murder Mountain — including from Rodriguez’s mother, Pamela (“Mela”) McGinnis — read as follows:

In the days of yesteryear when one wanted to voice a complaint about a public official or a governmental body they went to the town square, the courthouse, or posted up on a sidewalk to air their concerns. In the digital age of today some of those complaints are posted to the social media accounts of public officials or governmental bodies. Sean Riordan, senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, told the Outpost recently these social media accounts are essentially the new version of those old public spaces — something called a traditional public forum.

“[A traditional public forum] is what we think of as a place where communication has traditionally been essentially uninhibited — the public square, the town hall, these sorts of locations,” Riordan said. “And so in translating that to the internet, you can think about whether a social media website essentially performs the same function of being a space where the populace can communicate with each other and with their elected representatives or the officials that exercise authority.”

Riordan went on to say that if a social media account is being used in a way that aligns with “issues related to governance,” then comments made to the page should not be subject to any sort of censorship.

“If a [social] media account is essentially equivalent in terms to a traditional public forum, then there ought to be full First Amendment protections for people posting comments critical of government,” Riordan said. “It is just basically a translation of traditional First Amendment principles in this new world where so much dialog occurs online.”

Laws surrounding the censorship of social media comments are vague, but a handful of court cases have pointed to allowing full First Amendment protection in these circumstances — especially in terms of “viewpoint discrimination.” However, given the obscurity of the law and the slow, arduous process in seeking justice for a deleted or hidden comment, Humboldt County officials can seemingly act with impunity.

Samantha Karges works as the public information officer for the Sheriff’s Office and has been in her position since November 2017. Karges said she and Sheriff William Honsal oversee the social media accounts which include Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and a YouTube channel.

“Social media is the way the world is turning to in being able to stay up to date,” Karges told the Outpost. “It has been a great way for us to be involved with the community. We want to be able to put out our relevant information so [the public] won’t miss it.”

The Sheriff’s Office uses its social media accounts to post press releases, breaking news and community outreach events. Karges said it does not block users, but pointed to its social media policy, which states that the office “reserve[s] the right to hide or delete posts.” When asked what right she was referring to, Karges said, “Anyone who controls the page has the right to control what’s on the page.”

While that is surely true for individuals and their personal profiles, there is a bit of ambiguity when it comes to a page “owned” and operated by a government agency. The Sheriff’s Office is Facebook-verified with a “gray badge” indicating that it is a “business or organization Page.” (There is a difference between a profile and a “Page.” Click here to see Facebook’s explanation.)

The Sheriff’s Office social media policy can be found along the right side of its Facebook page, and states the Sheriff’s Office welcomes “relevant and appropriate contributions and comments,” and warns that the opinions of the commenters “do not reflect the opinions of the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office.” According to the policy, the office can remove or block comments that have profanity, offensive comments that target certain ethnic groups, comments that contain sensitive information, and any comments that promote “particular services, products or political organizations/candidates,” among others.

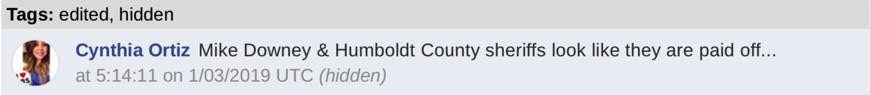

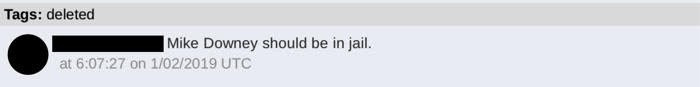

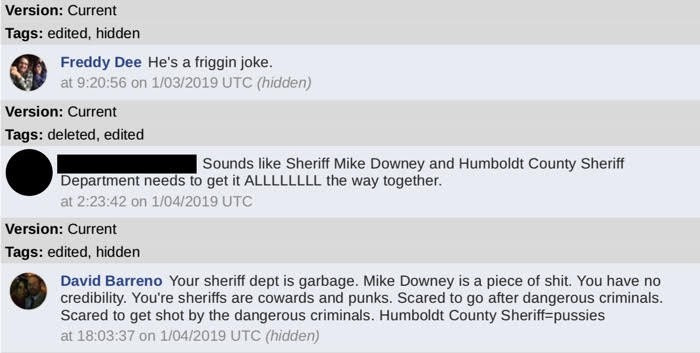

Critiques of public officials on social media accounts, whether rooted in fact or conspiracy, have been upheld by courts as being within the protected realm of the First Amendment. But the Sheriff’s Office, for one, doesn’t always exactly treat them as such. One comment on a Sheriff’s Office post from Dec. 26, 2018 was critical of former Sheriff Mike Downey and claimed he was “being paid off.”

Earlier this year the U.S Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld a lower court’s ruling that a government official violated the First Amendment rights of one of their constituents by deleting a post. The case, Davison v. Randall and Loudoun County Board of Supervisors, details how Phyllis Randall, chair of the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors, violated Brian Davison’s rights by deleting a Facebook post where Davison alleged members of a local school board were corrupt. Randall said she felt the allegations were “slanderous” and that she didn’t want them on the Facebook page dedicated to her role on the Loudoun County Board of Supervisors.

In Davison v. Randall and Loudoun County Board of Supervisors, the Fourth Circuit ruled that the deleting of Davison’s post alleging corruption among members of the school board constituted a viewpoint discrimination.

“Although Randall stated that she had ‘no idea’ whether Davison’s allegations were ‘correct,’ she nonetheless banned him because she viewed the allegations as ‘slanderous’ and she ‘didn’t want [the allegations] on the site,’” the Fourth Circuit concluded. “Randall’s decision to ban Davison because of his allegation of governmental corruption constitutes black-letter viewpoint discrimination. Put simply, Randall unconstitutionally sought to ‘suppress’ Davison’s opinion that there was corruption on the School Board.”

Karges said her office’s social media policy is approved by the county counsel, and she felt that the hiding and deleting of certain comments were not in violation of the First Amendment. (The Outpost reached out to the county counsel’s office and has not yet heard back.) Karges said the Sheriff’s Office Facebook Page falls under what is called a “limited public forum,” therefore making it, as Karges put it, “not an open public forum.” However, even under a “limited public forum” those in power still cannot limit access to speech when it comes to expressing one’s views.

Other than Karges stating that the Sheriff’s Office has deleted posts that “were in violation of [their] social media policy,” the Outpost couldn’t find any evidence of the deletion of posts in the public records request it obtained. In over 700 pages of hidden and deleted comments obtained by the Outpost, there was no sufficient way to tell if the comments were deleted by the original poster or by the Sheriff’s Office.

The Davison ruling took place in the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, and so the guidelines and parameters of the ruling do not necessary apply to Humboldt County which is in the Ninth Circuit. Riordan of the ACLU said that short of filing a lawsuit there isn’t much that people can do if their posts have been deleted or hidden by government officials.

“They could bring complaints to a Board of Supervisors if it is a county-level official, but this is all somewhat new,” Riordan said. “There is some law on it, but because it’s relatively new, no formal institutions has been set up to try to allow for these sorts of grievances to be aired outside of the courts.”

Riordan said he has not looked specifically at the policy of hiding posts, but felt that there “would be a strong claim that would be impermissible under the First Amendment as well.” Riordan went on to say that the ambiguity surrounding social media and the First Amendment is quite clear in his opinion.

“Even though these particular spaces are new, the principles that we are talking about applying are quite well established,” Riordan said. “It shouldn’t be controversial that the First Amendment protects against the kind of censorship that we have seen public officials engage in on these websites.”

###

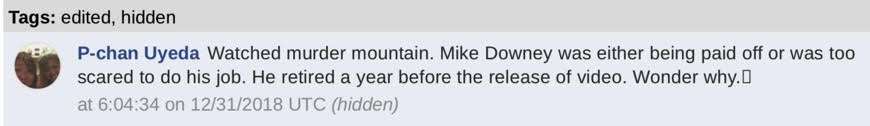

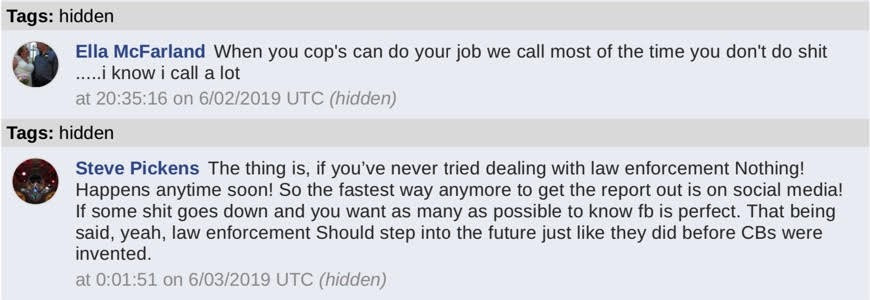

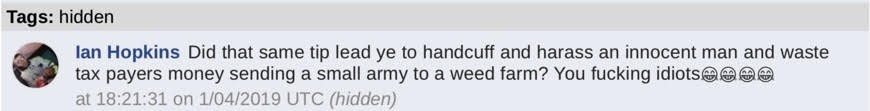

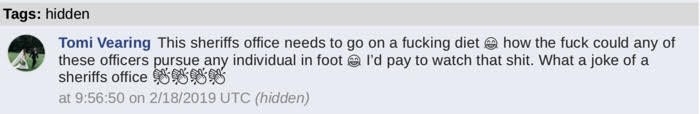

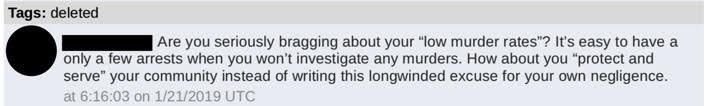

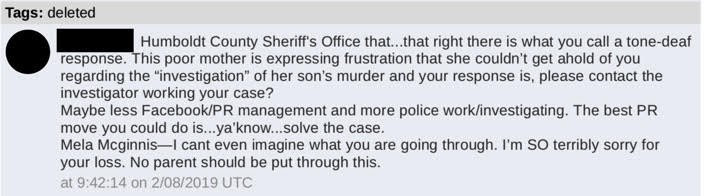

Here are more comments hidden or deleted from the Sheriff’s Office’s Facebook page. (The Outpost has hidden the identity of the commenters who were deleted, as we can’t be certain whether the Sheriff’s Office or the commenters themselves deleted their words.)

CLICK TO MANAGE