California is laying the groundwork for the next, slightly scary, phase in its push toward zero-emission transportation: self-driving cars packed with computers using finely tuned algorithms, high-definition cameras, radar and other high-tech gadgetry. What the driverless cars won’t feature: steering wheels, brake pedals and gas pedals.

Autonomous vehicles, mostly electric, are already here in a limited fashion — as a slow van, for example, to move people around a Bay Area office park. That kind of shuttle, and small delivery trucks, will likely be the first self-driving vehicles in wide use, employing GPS, 3-D imaging and other technology to process and respond to what their cameras see on the road: other cars, pavement markings, traffic signals, pedestrians, etc.

Officials say automated cars will dovetail in two ways with greenhouse-gas-cutting policies in California, where the transportation sector belches out nearly half of the state’s climate-warming emissions. They’ll be included in the fleets of ridesharing companies, reducing the number of personal cars on the road as the state transitions to electricity-powered transportation. And they’ll almost certainly operate on batteries (though some could run on zero-emission hydrogen fuel cells), helping motorists wean themselves off gasoline.

If properly managed, the coming driverless-car revolution could address other vexing problems as well, said Daniel Sperling, who directs the Institute of Transportation Studies at UC Davis. He cited his sister’s poor peripheral vision, which prevents her from driving.

“It could lead to a dramatic improvement in safety, a dramatic improvement for mobility for the elderly, for physically disabled people and for low-income communities,” he said. For many, autonomous vehicles will mean emancipation.

In addition, computer-driven cars are expected to reduce fatalities. They will never be afflicted with road rage, will not stop off after work for one too many and won’t nod off after endless hours on the road. And productivity could rise as motorists who now lose hundreds of hours idling in traffic each year are freed from the tyranny of paying attention and can legally text, work, answer email and even watch YouTube.

But it’s a significant step from allowing testing of automated cars in protected, supervised settings to unleashing them solo on the road, which experts say remains on a far horizon. There is much to be perfected: how best to turn left in traffic, for example, a maneuver that bedevils many human drivers. Multiply that by many more dicey scenarios and it makes sense that test vehicles’ current response to most obstacles is to just slow down.

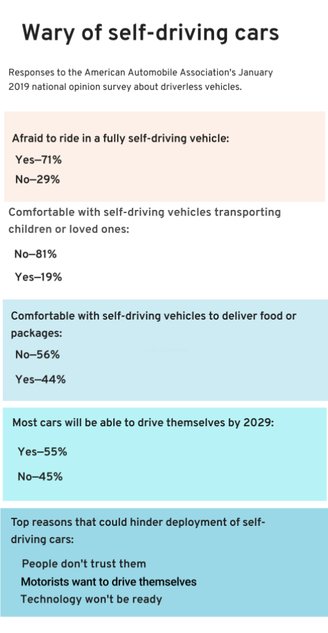

Although the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration says human errors cause 94% of serious crashes, motorists are reluctant to turn over the controls to computers, telling pollsters they prefer to drive a car, not interface with one. And the potential for hacking has led some doubters to paint a future in which bad actors “weaponize” a vehicle, taking over the controls with harmful intent.

Still, California is pressing ahead. It was among the first states to contemplate a future for autonomous cars, when the Legislature in 2012 authorized the Department of Motor Vehicles to devise rules for them. Those regulations are now the nation’s most extensive; in April the DMV proposed allowing testing of autonomous lightweight delivery trucks.

“You have to know what you are regulating, and we had to go to manufacturers to understand the technology,” said Brian Soublet, the DMV’s chief counsel, who has been writing the regulations since 2014 and is excited about leading the way. “We had to start from scratch….My kids are tired of hearing about it, but to me it’s completely fascinating — the future of how we are getting around.”

The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research has set out principles, such as prioritizing emissions reduction and more car-sharing, to help guide future state policies on smart cars.

And California’s controversial 2017 gas-tax increase encourages the transportation department and local jurisdictions to tap road funds to build infrastructure that smart cars will require, such as traffic lights that tell them how much time remains on a green light and freeway signs that announce their messages digitally.

The DMV has doled out permits to more than 60 companies for testing autonomous cars — nearly 800 of them — on California streets. Those vehicles have traveled more than 3.6 million miles and have been involved in 177 collisions.

It’s not a free-for-all. Testing has been allowed since 2014, in nearly every case with a human “safety driver” on board, able to take over the car’s controls. And, although one company, Waymo, has a permit to conduct tests without a driver, it has yet to do so.

The future can be glimpsed at a former Navy base near the Bay Area city of Concord, converted to the nation’s largest autonomous-vehicle proving ground where computer-driven cars are let off their leashes and are free to roam across 2,100 acres. The facility, GoMentum Station, run by the American Automobile Association, is an innovation hive where Silicon Valley marries its futuristic vision to the automobile industry’s traditional know-how.

California could reap economic benefits from a smart-car industry, attracting new business and jobs, officials say. Researchers forecast that investment in the technology, by traditional industry players and newcomers alike, will grow to $85 billion nationally through 2025, on top of $225 billion in spending on electric vehicles through 2023.

Randy Iwasaki with an autonomous bus, deer decoy and other objects in a GoMentum Station warehouse | Photo by Maria J. Avila for CalMatters

This transformation in transportation is taking place in a deceptively modest setting. The testing area has all the dusty charm of an abandoned town: shuttered buildings and empty parking lots, along with cattle, wild turkeys and coyotes wandering freely.

That’s perfect in the eyes of Randy Iwasaki, executive director of the Contra Costa Transportation Authority, which is a partner in the facility. He guided his electric (though not autonomous) car along some of the 20 miles of rough streets on a recent day.

“Look at this road, it’s cracked, you can barely see the center line it’s so worn, there are weeds growing all over,” Iwasaki said with a trace of pride. When testing first began, researchers had to mow the streets because the earliest automated vehicles perceived that they had wandered off-road. The imperfections provide excellent preparation for the vehicles to navigate California’s bumpy, clogged and often chaotic streetscape.

The facility also features 45 types of intersections, various railroad crossings and a warehouse full of “targets” — vinyl deer decoys, pedestrian mannequins, bicycles and traffic cones. Such accessories help the vehicles “learn” to process what they see and make decisions through artificial intelligence.

“The camera vision is great, but the perception is not always there,” said Huei Peng, who directs an autonomous-vehicle research program at the University of Michigan. “The vehicles can see, but they can’t always understand.”

Iwasaki explained this in people terms: At age 24 or 25, humans may be at the peak of their acuity, with quick reflexes and excellent vision. But drivers of that age lack a broad base of experience to make informed decisions about the safest responses in traffic. The current generation of automated vehicles, Iwasaki reckons, is still in its 20s and has much to learn from errors on the road.

That ignorance of some learned conventions and courtesies of driving gives many motorists pause. But they can relax: California is a long way — a decade or more — from hosting truly autonomous cars on city streets.

Iwaskai said most autonomous cars being tested in California are operating at very low speeds, almost crawling. That’s because their computers need time to analyze what they are seeing. “If computers got faster you could drive faster, but they are not ready to make that jump,” he said.

Uneasy about self-driving cars? Your vehicle is partly autonomous if it has such features as cruise control, parking assist and lane-keeping notifications. If you own a Tesla, you may have the highly advanced Autopilot, which makes decisions about steering and speed that maintain the vehicle within its lane.

What’s critical is the programming instructions companies feed to their computers to teach them decision-making of the sort human drivers make every day: Is it appropriate to break the law and cross a double yellow line to avoid an accident? Is it ok to drive on the shoulder to get around an obstacle?

An autonomous bus at GoMentum Station. Photo by Maria J. Avila for CalMatters

Programmers use real-world experiences, like the cars get at GoMentum Station, to build databases enabling the vehicles to make split-second decisions as people do.

Bernard Soriano, deputy director of the state DMV, said his agency issues a driver’s license when a human exhibits a “minimum set of skills” and can be expected to improve over time. Autonomous cars will be held to the same standard, he said. At the moment, the state requires manufacturers to self-certify that their vehicles operate within the rules of the road — not exceeding the speed limit or crossing double lines, for example.

Autonomous vehicles are programmed to be cautious, to put safety first and to always obey the law. That typically translates into low speeds and frequent braking, trying the patience of the humans involved in the testing.

That makes for a sobering real-world scenario: What happens when fleets of law-abiding, speed-limit-adhering cars hit the road and mingle with California’s sometimes willful motorists, known to call their own shots?

“It’s an ongoing discussion,” Soriano said.

###

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE