The Times-Standard building on Sixth Street in Eureka. | Photo by Andrew Goff.

On Monday, the Times-Standard issued a publisher’s note headlined, “Culture change is hard and necessary … and we’re just fine.”

John Richmond, the paper’s publisher/general manager/advertising director, as well as director of sales for T-S parent company MediaNews Group’s NorCal Division, declared in the first paragraph, “The Times-Standard is doing just fine.”

His column referred in general terms to layoffs made over the past few years, to the shifting business model of newspapers, and to various changes he’s implementing in an effort to increase readership and revenue. And he reassured readers of the paper’s ongoing commitment to journalism.

That afternoon, Richmond called Dan Squier, the Times-Standard‘s courts reporter, and fired him. It was the latest in a series of involuntary departures from the T-S newsroom in recent weeks.

Last month, on Aug. 30, the Times-Standard laid off Squier’s colleague Robert Peach. Peach reported news stories, worked nights on the copy-editing desk and wrote columns for the Sunday edition.

A month before that, back on July 27, the Times-Standard laid off Shaun Walker, who’d been employed by the paper for just shy of 25 years. He was the last remaining photographer on staff.

In recent interviews with the Outpost, Squier and Peach described a much different state of affairs at the Times-Standard than the one evoked by Richmond’s publisher’s note. They said the newsroom staff has been cut to the bone, and then cut again. Morale among the remaining reporters, they said, has rapidly plummeted. And with only two news reporters left on staff, as of this week, they expressed concern about whether Humboldt County’s daily newspaper of record can survive and fulfill its mission in any meaningful way.

# # #

Peach may have been the most highly educated cub reporter in the 165-year history of the Times-Standard. He was hired this past December, seven months after earning his PhD in philosophy from the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley.

During an interview at Outpost headquarters this past Thursday, Peach said the Times-Standard job gave him a great entrée into journalism, allowing him to follow his passion for writing while working in a much faster-paced environment than the buttoned-up world of academia.

“It’s been good for me to step into that mode where stories are happening, and they matter — and it’s important to get them out as soon as possible,” he said.

The bustling pace may not have come naturally for Peach, who was pensive and deliberate with his words during our interview, but the newsroom staff welcomed him, showed him the ropes. He loved the camaraderie and the job.

“I miss it,” he said. “It brought a lot of meaning to me.”

Temperamentally, Squier is pretty much the polar opposite of Peach — brash and impetuous. He came by the Outpost office Tuesday morning after one last trip to the Times-Standard, where he turned in his company cell phone and key fob and received a packet of termination papers. He was obviously still reeling.

“I’m so fucking disappointed,” Squier said. “Personally and professionally.”

Squier declined to talk on the record about why he’d been fired. “I don’t want to because it’s still a sensitive issue, and I say that out of self-protection,” he said. “And I’d rather not go into that because it’s actually ancillary to the story. The story is the dissolution of the paper of record.”

Peach said something remarkably similar five days earlier: “My focus is less on the loss of a position than the loss of an institution. I think, for me, that’s the story.”

According to Squier, other T-S employees have left or been been laid off in recent months, too, including the IT manager and several people in the business office. In an effort to save money, he said, the company doesn’t intend to fill any of those vacancies.

# # #

I should note for the record that before taking his current job at the Times-Standard/MediaNews Group in February, Richmond was CEO of the Outpost’s parent company, Lost Coast Communications, Inc., meaning he was my boss. This arguably makes me a less-than-ideal person to write a news story involving him. For what it’s worth, he and I had a friendly working relationship. We even got a beer together after he took the new job: no hard feelings.

I reached out to Richmond for this story. Specifically, I sent him an email late last week with the subject line “Interview?” I told him I was working on a story about the recent developments at the T-S and asked if we could talk on Monday or Tuesday of this week. He agreed. We exchanged a couple emails trying to nail down a time.

Then, on Monday afternoon — after Richmond published his publisher’s note but before he fired Squier — he sent me the following email:

Hi, Ryan.

Just rereading your email and when you said “talk” I’m worried you thought I meant I would submit for an interview. That was not my intent.

Instead, I’ll just refer you to this Publisher’s Note we put up recently. It can be considered my official comment on matters pertaining to the “recent developments over there at the T-S”.

Thanks, John

I should also note that I worked at the Times-Standard more than a decade ago, first on the copy desk, proofreading and laying out pages into the wee hours, and later as the paper’s business reporter (one of several positions that no longer exist there). It was my first full-time reporting gig, and like Peach I found it both rewarding and educational.

At the time of my employment, in 2007 and 2008, the Times-Standard was engaged in an old-fashioned newspaper war with the upstart Eureka Reporter, a free daily established by local finance-industry tycoon Robin P. Arkley II, who hoped to drive the T-S out of business.

Intent on preventing that outcome (and, by some accounts, provoked by a personal dislike of Arkley), MediaNews Group’s then-CEO, Dean Singleton, kept the T-S newsroom well staffed. We had seven full-time news reporters, three sports reporters and three feature writers (including the North Coast Journal‘s current editor, Thadeus Greenson). We also had three copy editors/page designers, a city editor, a managing editor and a number of freelancers.

The Eureka Reporter went belly-up in November 2008, and with the great Humboldt County newspaper war over — not to mention the precipitous decline in advertising revenue across the industry — staff numbers at the Times-Standard began to dwindle. In 2012 the Times-Standard stopped printing a Monday edition of the paper, and circulation numbers shrank.

The Times-Standard‘s Wikipedia page includes an outdated circulation figure of 23,000 copies. I couldn’t find current numbers, but until 2016 the Times-Standard was a member of the Alliance for Audited Media, a nonprofit industry group that collects circulation reports. The last report the Times-Standard submitted, for the fourth quarter of 2016, said average weekday circulation had dropped to 13,446, and fewer than 10,000 copies were printed on Sundays. Squier said he doesn’t know the exact figures, but circulation numbers have continued shrink.

Much has been written about the dramatic decline of newspaper fortunes in the internet age. The broad strokes go like this: Craigslist and Facebook came along to steal classified revenue, which had been a longtime source of inflated profits for daily newspapers, while online news sites and social media trained a new generation that they can get their news for free. Newspaper publishers, meanwhile, were slow to comprehend and adapt to this sea change, and for the most part they failed to develop viable new business models.

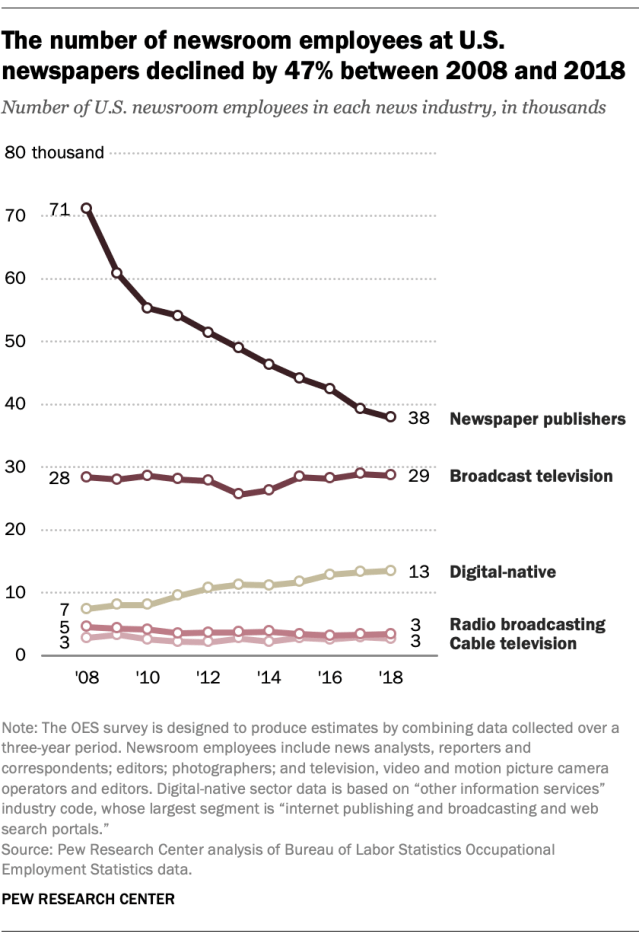

Between 2008 and 2018 the number of employees in newspaper newsrooms fell by 47 percent, representing a loss of about 33,000 jobs. Online newsroom employment grew over that period but only by about 6,100 jobs, not nearly enough to offset the newspaper losses.

These industry woes have been exacerbated and exploited by corporations such as Alden Global Capital, the hedge fund parent company of MediaNews Group, which (somewhat ironically) is now known as Digital First Media. Through that holding company Alden has become the country’s second-largest newspaper chain. It owns the Denver Post and more than 100 other local newspapers, including the San Jose Mercury News, the Marin Independent Journal and the Times-Standard.

Across the journalism industry Alden Global Capital is both feared and reviled. Washington Post media columnist Margaret Sullivan described Alden as “one of the most ruthless of the corporate strip-miners seemingly intent on destroying local journalism.”

The Nation struck a similar note in April, calling Alden “one of the slimiest corporate villains of our time” and reporting that since the company took control of Digital First Media in 2011, “executives have eliminated a staggering two out of every three staff positions at its media properties.”

Indeed, Alden has become notorious for eviscerating newsrooms while extracting the profits. The Washington Post recently reported that Alden moved nearly $250 million from newspaper workers’ pension savings into its own investment accounts, prompting an investigation from the U.S. Department of Labor.

Alden’s top executives, meanwhile, have extracted at least $241 million in cash from Digital First Media and “rewarded themselves with tens of millions of dollars’ worth of prime real estate in Florida and the Hamptons,” according to The Nation.

Industry analysts say these “vulture capitalists” have no interest in actually investing in journalism. “There is no long-term strategy other than milking and continuing to cut,” media writer Ken Doctor told industry publication NewsGuild last year. “Their view is that in 2021, they’ll deal with that then. Whatever remnants are there, they’ll try to find a buyer.”

# # #

Squier is well aware of Alden’s reputation, and he said the Times-Standard isn’t the only Alden-owned paper in the region to lose staff this year. Reporters at the Chico Enterprise-Record and the Paradise Post — both owned by Alden/Digital First Media — worked day and night covering last year’s Camp Fire, the most destructive wildfire in state history. Ten of them lost their homes in the disaster.

But in the process of covering the disaster the reporters apparently blew through the overtime budget for Digital First Media’s NorCal Division. Squier estimated that a dozen other newsroom employees were laid off across the region around the time that T-S photo editor Shaun Walker got the boot.

Walker declined to comment for this story except to say that he’s still in the area, working as a freelance photographer. And Peach said a confidentiality agreement prevents him from discussing the reason he was laid off. But he did describe the experience.

“The way they work it, it’s so mechanical and just kind of … inhumane,” he said. “They usher you out of the building without allowing you to collect your belongings.”

The newsroom couldn’t have seen this coming early in the year. Morale was high, Peach said, “especially with the introduction of the new publisher.” But Walker’s unexpected departure marked a turning point. If an employee with nearly a quarter-century on the job could be dismissed, apparently without cause, was anyone safe?

“John [Richmond] called us in for a staff meeting the following week,” Peach said. “I came in somewhat late, but I know it was fraught with tension. People were vocal about office morale and their sense of not being advocated for … and feeling really insecure about our jobs.”

Squier said losing Walker amounted to losing the entire photo department, “and I’ve never worked in any newsroom at any newspaper that didn’t have a photo department.” But beyond that, he said, Walker brought an institutional knowledge and community relationships that were integral to the way staff put together the paper each day.

“The day Shaun got laid off I updated my résumé … because I am not going to stay on the sinking ship,” Squier said. “Now you only have two people doing the reporting. I mean, it’s bad enough when we had four.”

Squier suspects the downsizing is all about money and corporate directives. “I get the sense that this is just yet another corporate slashing. … And when I push back at it, I get fired.”

The length of stories in the Times-Standard is getting slashed, too. This was among the changes Richmond described in Monday’s publisher’s note. “We’re bringing our word counts down and article counts up,” he wrote. “You want more news and faster. We’re on it.”

Peach said reporters were recently told that their quota had increased from two stories per day to three. And according to both Peach and Squier, Times-Standard Editor Marc Valles recently started sending reporters their internet traffic data, showing how many clicks each of their stories had gotten.

To Peach this focus on numbers and quantifiable output seems wrongheaded.

“It’s just unreasonable if you’re looking to create good content,” he said. “And for me, at least, the point of focus is so … what’s the right word for it? The priorities are upside down in terms of how we can reach readers and increase readership.”

Perhaps it was a sign of how recent their departures were or how connected to their jobs they’d become, but both Peach and Squier kept slipping into the present tense and using collective pronouns while discussing the Times-Standard newsroom.

Regarding those web traffic numbers, Squier said, “The reporters are feeling utterly confused as to why that metric is being applied to them as if it means something.” The problem is the Times-Standard‘s paywall, he said. As with many other daily newspapers, the T-S website only allows non-subscribers to see a few stories for free each month before locking them out.

“That’s why people aren’t clicking on your stories,” Squier said.

Peach suspected that the web-traffic numbers were intended to inspire competition among the reporters, but instead the data just further deflated morale.

“It’s kind of an energy suck, particularly for people who put in tons of effort and work.” Longer, more thoroughly reported stories often don’t get the amount of clicks as short and flashy stories. “Like, the breaking crime [news] seems to get a lot of traffic,” Peach said. “So it’s demoralizing, I’d say, is the effect of that.”

Squier was plainly angry for much of our interview, but at one point he lowered his head, looking despondent.

“God, I’m gonna miss the fucking courts,” he said, almost under his breath. “God, I learned so fucking much.”

A few minutes later he was angry again, thinking about the loose ends, the stories he hadn’t finished reporting.

“There’s only 20 open fucking murder cases in this goddamn county I was covering,” he said. “Literally, there’s 20 open homicide investigations in Humboldt County right now. And who’s going to cover them for the paper of record?”

Squier believes that the version of the Times-Standard that the community grew to know and trust is now gone, that there’s no way for a news staff of two reporters and two editors to cover a county of 135,000 people spread across an area nearly the size of Connecticut.

“It’s a huge loss,” he said. “It’s a huge personal loss and it’s a huge institutional loss. And [management] can claim it’s still there all they wish, but all you have to do is pick up your paper tomorrow and tell me what you think. Because it’s going to be short, and filled with bleah.

“You’re not going to get a 40-inch story on corrections deputy Corey Fisher, and an 11-day trial about how he abused kids and abused inmates. You’re not going to get the story on the Rio Dell murder. You’re not going to get any follow-up investigation on that. You’re not going to get anything on Josiah Lawson.”

The Times-Standard has actually been down to just two news reporters before, and then built the staff back up — impressively. Many locals have remarked over the last six to nine months how impressive the crew was over there, a dedicated, hard-working and hard-nosed collection of reporters, almost all of whom came here from out of the area because they wanted a job in journalism.

Peach said feedback from the Times-Standard‘s monthly reader board meetings was always positive, with people saying the paper’s writing and content had improved over the past year.

But several of the people who produced that content are now gone, and this time, the terminated reporters say, they won’t be replaced.

# # #

Richmond is still out hustling, though, telling local community members about the importance of newspapers generally and the Times-Standard in particular. He addressed Rotary Club of Arcata Sunrise on August 23, telling local business leaders some of the same things he later wrote in his publisher’s note. (Video of the meeting was published to YouTube but got taken down late last week. Arcata Sunrise Rotary did not respond to an email asking why.)

Richmond said a few other things, too. He laid some of the blame for newspapers’ declines on the incomprehension of young readers. “Kids aren’t taught the difference between opinion and real journalism,” he said. “They don’t know what the value of in-depth reporting is; they don’t know what in-depth reporting even looks like.”

He said the Times-Standard is “pivoting” in the way it publishes content, moving toward a model based on the San Francisco Chronicle‘s sfgate.com, where some content is free. “And I’m yelling at my reporters a little bit,” telling them to publish press releases faster, he said.

And he urged those in attendance not to take real journalism for granted.

“If this matters to you, as leaders of this community, please, tell your local businesses, support local journalism. And it doesn’t have to be me. If you hate the Times-Standard ‘cause you don’t think we cover Trump the right way … give it to the Mad River Union. Give it to the Ferndale Enterprise, you know. Give it to somebody in print or somebody in TV or somebody in local radio who is creating local, real journalism.”

CLICK TO MANAGE