Alice Crisci gave birth to her son Dante years after paying out-of-pocket to preserve her fertility, which was jeopardized by her cancer treatment. Photo by Iris Schneider for CalMatters.

###

What role, if any, should the state play in ensuring that Californians who want a baby can have one?

It’s an emotionally charged issue for people struggling with infertility who can’t afford procedures such as in vitro fertilization. While 14 states require insurance companies to cover infertility treatment — and most of those include in vitro — California does neither. Health insurers have long maintained that paying for such procedures would force them to raise premiums for everyone.

This year the Legislature once again refused to pass a bill requiring insurers to provide broad coverage of in vitro fertilization. But a more tightly targeted bill is advancing and headed for a final vote: It aims to clarify that insurers must cover the cost of preserving eggs, sperm or embryos for patients whose treatment for diseases such as cancer could destroy their ability to have children.

Neither, however, would benefit the one-third of low-income Californians who receive their health care through the state-administered Medi-Cal program.

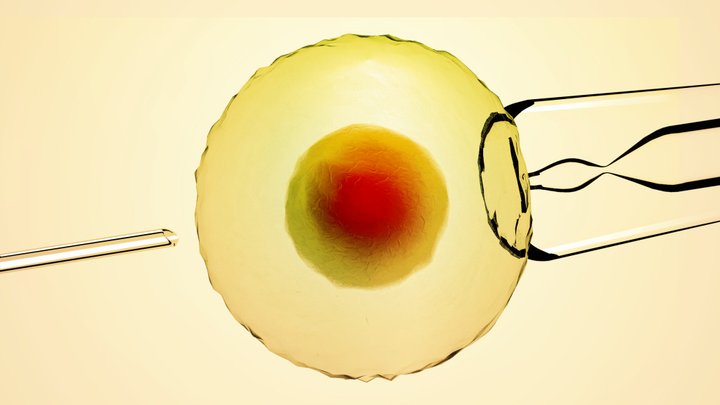

The average cost for in vitro fertilization, also known as IVF – where eggs are retrieved and combined with sperm in a lab to create an embryo — is $10,000 to $15,000, with an additional $5,000 to $7,000 for medication.

Alice Crisci of Los Angeles remembers those costs quite well.

She was diagnosed with cancer at age 31 and had 5 days to figure out how to preserve her fertility and pay for it herself. That meant a quick in-vitro fertilization — creating embryos in a lab from her eggs and a donor’s sperm — and then a second part years later to have a frozen embryo implanted in her body.

“I was lucky that I had enough room on my credit card to pay for it,” said Crisci, who had the procedure when embryo freezing was more reliable than egg freezing. “There was just one shot at being a mom.”

Eventually, she said, she charged up $80,000 in medical debt and was forced to file bankruptcy.

Alice Crisci and her son Dante hang out after school. A former cancer patient whose treatment put her fertility at risk, she said she went into debt to preserve her ability to have a child. Photo by Iris Schneider for CalMatters

Today she has a 5-year-old son and no regrets — and is contemplating having a second child from one of her stored embryos. Again, she would need to pay for it herself.

“When medical care harms a system of the body, then the medical system needs to take care of that part. This is no-brainer preventative medicine,” said Crisci, who started a charity called Fertile Action to advocate on fertility issues. “We know your hair is going to grow back but your fertility is not going to. Not covering this is a huge breakdown in the health system.”

Crisci’s condition is known as iatrogenic infertility, caused by a medically necessary intervention. Many more people experience infertility for a variety of other reasons, such as abnormal sperm function in men or diminished ovarian reserve in women. In vitro procedures can allow them to conceive and bear children.

“IVF can be an important option for those who are experiencing infertility and want to have children, and we don’t dispute that. But adding $500 million in additional costs per year increases premiums for everyone.”

—Mary Ellen Grant, California Association of Health Plans

But critics counter that requiring health plans to cover expensive, elective fertility services would raise premiums by millions of dollars. California currently requires that insurers offer infertility treatment but it’s up to employers and groups to decide if they want to include it.

“IVF can be an important option for those who are experiencing infertility and want to have children, and we don’t dispute that. But adding $500 million in additional costs per year increases premiums for everyone,” said Mary Ellen Grant, spokeswoman for the California Association of Health Plans. “With health care affordability among Californians’ most pressing concerns, state leaders must factor in costs when defining what is and is not covered.”

“Everyone deserves the right to build a family, and it shouldn’t matter what state you live in,” said Betsy Campbell, chief engagement officer for RESOLVE, the National Infertility Association. “Cost should not be a barrier to getting the care you need. The only reason the word “expensive” is used is because the treatment for this disease is not covered by insurance.”

For now, advocates and insurers are focused on the advancing bill by Pasadena-area Democratic Sen. Anthony Portantino. It is intended to clarify that the state Department of Managed Health Care considers fertility preservation to be medically necessary basic health care — meaning that insurers are required to cover egg, sperm and embryo retrieval and freezing for patients who have a diagnosis, like cancer, that could damage their fertility.

Health insurers disagree, arguing that the coverage is not required and never has been.

Portantino’s bill originally would have applied to patients in Medi-Cal, which currently does not cover fertility preservation. But the state Department of Finance opposed that, saying it would result in “significant general fund costs, potentially in the tens of millions of dollars.” An aide to Portantino said because the bill aims to clarify current law, it is being amended to not impact Medi-Cal, which does not cover fertility preservation.

Currently 7 states require fertility preservation for those facing a medical condition that could impact their fertility.

The California Health Benefits Review Program, an independent organization under the UC system that evaluates health-related proposals, reported that if Portantino’s bill becomes law, nearly 1,800 Californians would take advantage of it to freeze their eggs, sperm or embryos in the first year alone. But it estimates it also would cause premiums to rise by $8.2 million for people in those plans.

Disputing whether fertility preservation is already required

The California Association of Health Plans contends that the fertility preservation bill aims to clarify a law the organization doesn’t believe exists — and that it would require plans to retroactively cover fertility preservation claims.

“Fertility preservation is not an existing benefit under current law,” said Grant, of the association. “That has been evidenced through many years of legislative attempts to add fertility preservation as a covered benefit.”

In addition, Grant said, health plans say the proposal lacks regulatory details that would provide the framework for how preservation would work, who would get it under what circumstances, how long insurers would be required to keep frozen tissue on ice, and what would happen if the person changes insurers or dies.

But the state’s Department of Managed Care, which oversees health plans, is adamant that fertility preservation is a covered benefit under the basic standards of care that govern required health coverage.

“The definition of Basic Health Care Services is defined by these broad categories in order to capture advancements as the medical standard of care evolves,” it wrote in an email. “There have been several advancements in recent years in the medical community regarding Fertility Preservation which has resulted in more provider recommendations to have fertility preservation services when it is medically necessary.”

Alice Crisci and her son Dante hang out after school. A former cancer patient whose treatment put her fertility at risk, she said she went into debt to preserve her ability to have a child. Photo by Iris Schneider for CalMatters.

Clinicians agree.

“My understanding is that it is a covered service for adverse cancer treatment,” said Irene Su, professor of OB/GYN and reproductive sciences and director of the fertility preservation program at UC San Diego.

“But the insurers are unwilling to cover this benefit because of the cost.”

The state agency said it began supporting fertility preservation after the American Society for Reproductive Medicine in 2013 issued new recommendations that egg freezing be offered to those facing chemotherapy or similarly harmful treatments. Last year the American Society of Clinical Oncology said that freezing of eggs, sperm and embryos is considered standard practice for fertility preservation for those with cancer.

Since 2017 the state has conducted 14 case reviews where an insurer denied preservation services, and overturned all but one case.

“That appeal process takes a lot of time and effort and that is something not a lot of patients have,” said Su, who treats young adults with cancer. “The burden to all insurers are rather small for something that could be a huge impact for a cancer survivor later.”

The difference of opinion has set up a battle between the state and Kaiser Permanente, the largest health care plan in the state with nearly 9 million members. In May, the state filed a cease and desist letter accusing Kaiser of failing to provide state-required “basic health care services” and “medically necessary” care because it denies requests for such services.

Kaiser argues that preservation is not a covered benefit because it was never mandated by the Legislature. It notes that the state has previously approved Kaiser’s riders – special add-on services for premium plans – for fertility preservation services. The department has since said that approval was a “mistake.”

“It is inappropriate for (the department) to try to circumvent the legislative process and attempt to mandate coverage that the Legislature, for valid reasons in the public interest of ensuring affordable health care, has long refused to mandate,” said John Nelson, vice president of Kaiser Permanente in a statement. “If an executive branch agency can simply declare a change in existing law despite the Legislature’s exclusive authority to legislate, the risk to the public interest becomes too great to overlook.”

Portantino’s bill aims to get the Legislature to settle the dispute. With the final days of the legislative session ticking down, it faces a final vote in the full Assembly.

Infertility coverage for everyone?

On hold is the more expansive approach introduced by Berkeley Democratic Assemblywoman Buffy Wicks, who asked California to follow the lead of the American Medical Association and World Health Organization and recognize infertility as a disease. Under current law, she notes, some insurers provide no coverage, some provide only diagnostic testing to identify the cause of infertility, and “very few” provide partial or full payment for treatments such as in vitro fertilization.

“Infertility is a diagnosed disease – and as with other diseases, these treatments should be covered by insurance.”

— Assemblywoman Buffy Wicks

It’s a personal crusade: Years ago she found out she suffers from ovarian dysfunction and opted to go through egg freezing preservation. Her costs were covered because she lived at the time in Illinois. Although she later conceived her 2-year-old daughter without in vitro, she contends that Californians deserve more fertility options.

Over time she amended her bill to narrow it: As of now, it would compel only insurers on the Covered California exchange, where consumers can purchase Obamacare coverage, to provide in-vitro fertilization as a standard benefit.

Requiring nearly all insurers to cover in vitro fertilization would increase premiums $537 million annually, the Review Program estimates. It found that the number of people undergoing the procedure would increase 350 percent in the first year. Currently, insurers are required only to offer IVF as a potential benefit if employers want to include it in their plans.

The bill stalled this session, although Wicks said she intends to bring it back next year.

“Many families, from every background, experience challenges with fertility. Infertility is a diagnosed disease – and as with other diseases, these treatments should be covered by insurance,” Wicks said in an email. “As it stands now, those with means can pay for these costly out-of-pocket expenses, but most families find themselves spending their life savings, or forgoing treatment. The ability to start a family should not be determined by your ability to afford out-of-pocket expenses.”

###

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE