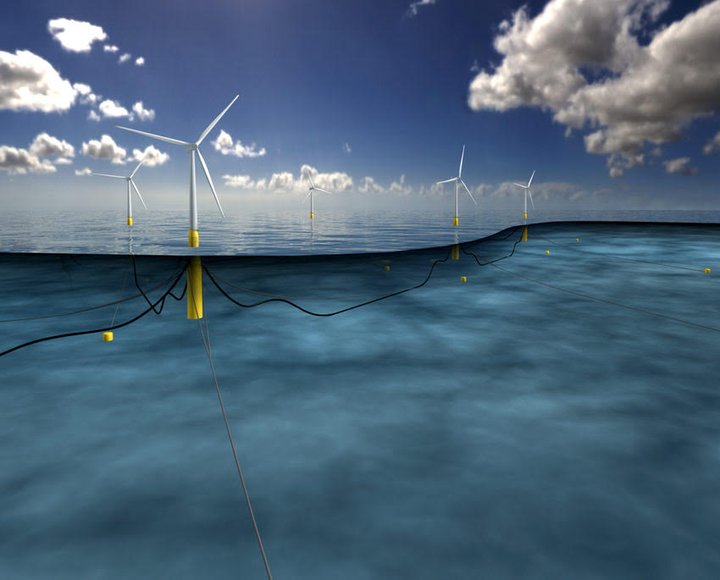

Floating offshore wind turbines like this one in northern Portugal may eventually be deployed off the Humboldt County coast. | U.S. Department of Energy.

Last month, under intense public pressure, the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors rejected the $300 million Humboldt Wind Energy Project, bringing a dramatic end to the most polarizing countywide policy debate this community has seen in years.

The project’s passionate critics voiced a variety of objections to the proposed wind farm, including its location on sacred Wiyot land, its potential environmental impacts and its ties to Big Oil. (The applicant, Terra-Gen, is owned by Energy Capital Partners, a private equity firm with investments in coal, oil and fracking.)

But even the loudest naysayers had no quarrel with wind energy itself. In fact, many public speakers — and several county supervisors — suggested that we already have a better renewable energy project on the horizon: offshore wind.

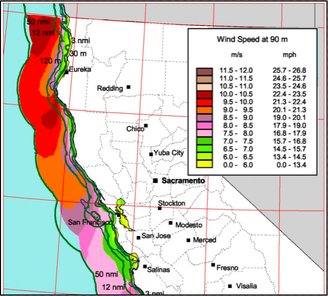

Wind speeds off the Northern California coast. | Source: U.S. Department of Energy

There’s reason for optimism. The air blowing off the North Coast is considered one of the best wind resources in the world, and probably the best in the continental United States, according to Dr. Arne Jacobson, director of the Schatz Energy Research Center at Humboldt State University. Wind speeds out there regularly exceed 20 miles per hour and remain fairly constant across seasons and around the clock.

“It’s an amazing resource,” Jacobson said.

But if anyone thought we could sidestep controversy by moving wind energy proposals from land to sea, well, think again. In conversations with the Outpost, local and regional stakeholders expressed serious concerns about a range of issues, including conflicts with the fishing industry, impacts to birds and marine life and more.

Which means that in the coming years, Humboldt will have to engage in another serious debate, weighing humanity’s increasingly desperate need for industrial-scale clean energy projects against the significant and, at this point, largely unknown impacts of such development.

# # #

Efforts to harness our world class offshore wind resource are well into the planning stages. Last May, at a hearing of California’s Joint Committee on Fisheries and Aquaculture here in Eureka, Senator Mike McGuire led a wide-ranging discussion with stakeholders exploring the possibilities, challenges and risks posed by floating offshore wind farms.

Not only could such projects help California reach its goal of 100 percent clean electric energy by 2045, they could also revitalize our port in ways that only the wildest of train-revival fanatics have dared to dream.

Kevin Banister, vice president of offshore wind development company Principle Power, told attendees at the May hearing, “We view Humboldt County as a place that, with investment, could become the shoreside hub for wind development along the entire coast of California.”

Jana Ganion agrees. She’s the sustainability and government affairs director at Blue Lake Rancheria, and for several years now she has served on an intergovernmental renewable energy task force organized through the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). (Disclosure: The Blue Lake Rancheria holds a sizable stake in Outpost parent company Lost Coast Communications, Inc.)

“I think it’s important to understand the full range of potential stacked benefits from this new, potentially enormous industry,” Ganion told the Outpost in a recent phone interview. She, like Banister, said Humboldt County stands to become the West Coast hub for research and development in the emerging floating offshore wind industry.

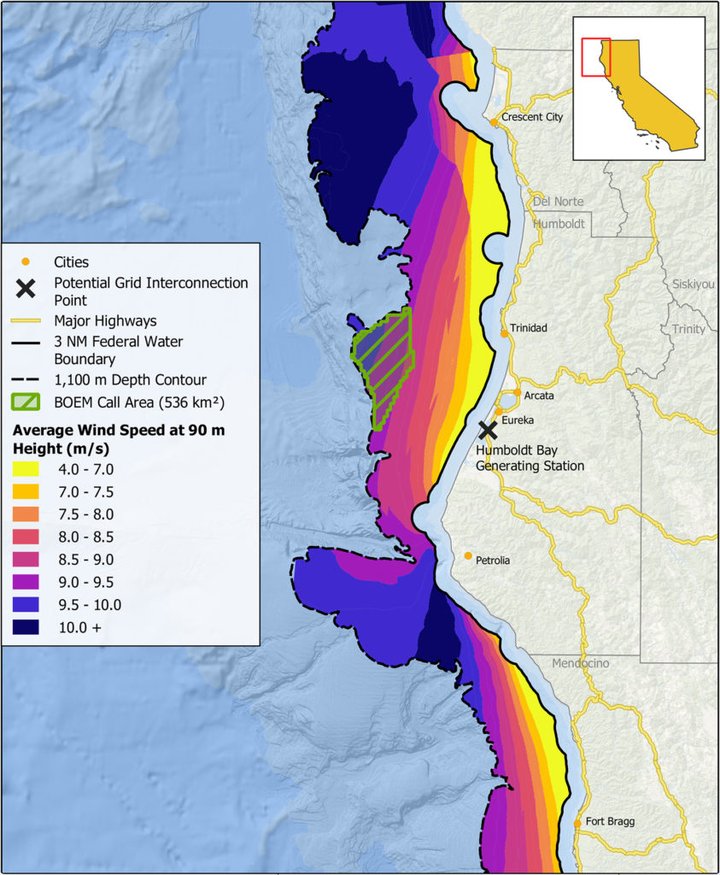

Here’s the biggest reason why: A roughly 200-square-mile area off our coast (in green below) is one of just three wind energy development zones identified by BOEM in a pitch to developers back in October 2018. The other two zones are off the Central Coast (Morro Bay and Diablo Canyon), and it turns out they conflict with military training activities. The Department of Defense has redlined those zones as off limits.

Map courtesy Schatz Energy Research Center.

That put the focus for development squarely on the Humboldt County “call area,” and more than a dozen firms or development coalitions answered BOEM’s call for interested parties. The vast majority said they’re interested in developing projects here.

One proposal is being led locally: a public-private partnership headed up by the Redwood Coast Energy Authority (RCEA) in association with EDP Renewables, Aker Solutions and Principle Power. (More on their plans below.)

The next step, expected within the next year or so, is for BOEM to hold a commercial lease auction. The winning bidder(s) will be poised to develop the first floating wind farm in the United States. (Wind farms off the East Coast can be anchored to the sea floor, whereas our narrow continental shelf means they’ll have to float in waters that are 600 to 1,000 meters deep.)

Ganion said the local community should be thinking bigger than just a single project.

“If we do have the first offshore wind deployment here off the coast of Humboldt, there are going to be lots of folks coming here to see it,” she said.

Not just tourists, either. There are still only a handful of floating wind farms in the world. (The first was deployed off the coast of Scotland in 2017.) If the industry takes root in and around our underused deepwater harbor, the Humboldt Bay region could see an influx of activity, including research and business development to fulfill the core and ancillary needs of the industry.

The Humboldt call area, located about 25 miles off our coast, could eventually host multiple wind farms. As part of a wide-ranging study on offshore wind here, the Schatz Center is studying three scenarios of possible deployment: 50-megawatt pilot-scale, 150 megawatts (about the size of RCEA’s proposal) and a whopping 1,800 megawatts, which is considered the full build-out potential for BOEM’s call area. (The figure was recently lowered from 2,100.)

At that scale — and probably even at the 150-megawatt level — our region would need significant upgrades to its electric transmission lines. (One possible solution? A subsea cable running from here to San Francisco.) We’d also need major renovations to our port infrastructure, and it’s not yet clear who might pay for it all. Regardless, the scope of this opportunity is clearly enormous.

A WindFloat prototype, built by Principle Power, being deployed in Portugal.

But the range of potential impacts is also huge, and many are concerned that the risks won’t be thoroughly explored before development begins.

Fishermen are among the most concerned. Harrison Ibach, president of the Humboldt Fishermen’s Marketing Association, expressed some of the industry’s reservations at the hearing in Eureka last May.

“This will permanently take away hundreds of square miles of fishing areas,” he said. State and federal waters are already “littered” with marine protected areas (MPAs) and other sanctuaries where fishing is prohibited, he argued.

“We cannot afford to lose any more fishing grounds. … It really seems like we are always under attack. We’re always fighting to defend our livelihoods. Fishermen are not against renewable energy,” he said, “but we are against permanently losing our fishing opportunities.”

Ibach also expressed concerns about the safety of the local fishing fleet, saying that being forced to avoid large floating wind farms could increase travel times back to shore in bad weather and funnel traffic into narrow channels.

Noah Oppenheim, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations, told the Outpost in a recent phone interview that the impacts need to be studied carefully.

“BOEM needs to create a sophisticated, dedicated process to evaluate the economic impacts,” he said. “I also have significant concerns about impacts on marine life.”

Fishermen have known for years, he said, that salmon and other species are attracted to electrical currents, and these floating wind farms will include networks of electrified cables suspended underwater.

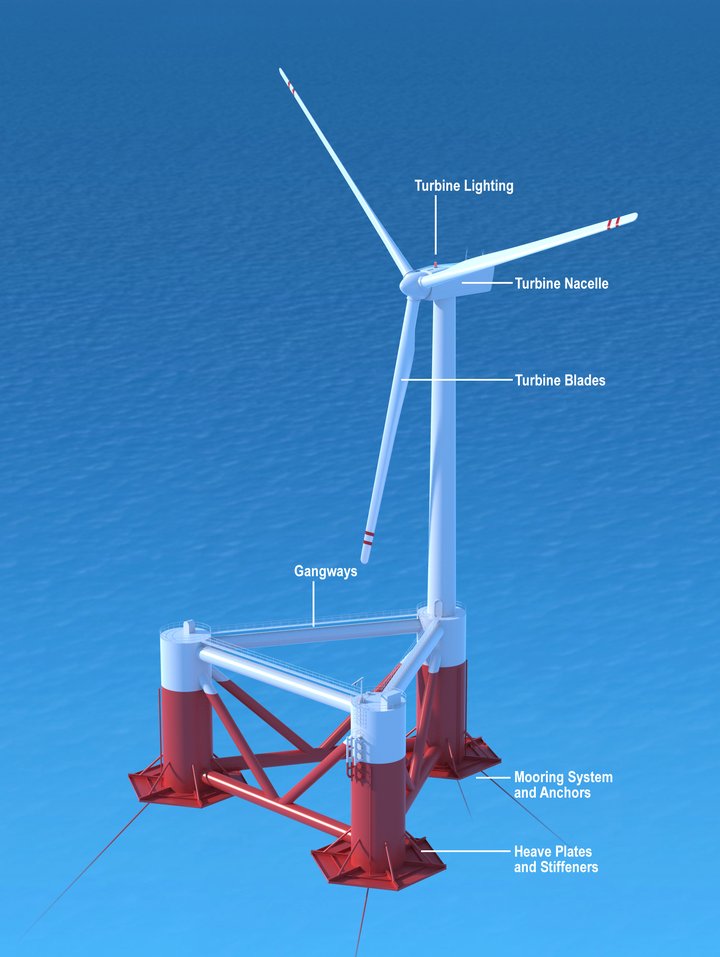

An illustration showing the undersea electric lines and anchor cables typical of a floating wind farm.

“We need to know whether or not large aggregations of salmon and others species will be attracted to these lines,” Oppenheim said. Predators such as sea lions may also be drawn to the area. “Are we going to see a predator trap, further diminishing fish populations?” he asked.

In 2010, former Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar launched an initiative to streamline the permitting process for offshore wind energy projects under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Called “Smart From the Start,” the program was designed to encourage clean energy development, but Oppenheim said it effectively weakened regulations by putting environmental scoping efforts in the hands of developers rather than government agencies.

“Not to accuse anyone of bias,” Oppenheim said, “but it means developers are doing the science. In my opinion, it’s better to have regulatory agencies with the scientific staff and expertise doing these preliminary evaluations.”

Hoping to exert more influence, fishermen are organizing. Just last week, the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance (RODA), a fishing industry coalition born on the East Coast, announced the launch of a Pacific Advisory Committee that will be an active participant in planning activities for floating wind farms on the West Coast.

“Having the fishing industry as a partner in those discussions is going to be key,” Oppenheim said. “We are raising our voices, raising our hands and saying, ‘Here we are.’”

Environmental leaders are speaking up, too. Jennifer Savage, California policy manager for the Surfrider Foundation (and a friend of mine), said the threats posed by climate change demand a swift and broad-based shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. “But we should not offer up our ocean, with its fishing grounds and wildlife, to private development without ensuring we have enough information about what harm could be caused,” she said.

Jennifer Kalt, executive director of Humboldt Baykeeper, agreed. “I’d say the potential impacts to whales, including orcas, may be the biggest concern from the environmental standpoint, but there are a lot of unknowns as far as what critters are out there,” she said.

The zone for proposed development is so far offshore that wildlife surveys have rarely been conducted.

“Very little is known about the bird component we have offshore here,” retired wildlife biologist and member of the Redwood Region Audubon Society Chet Ogan said at the hearing back in May.

At least 40 bird species rely on the offshore waters in our region, Ogan said, and floating wind platforms can create their own micro-environments. Algae will likely grow on the structures, attracting invertebrates, and the subsequent nutrient upwelling would attract fish which, in turn, would attract pelagic bird species such as albatrosses and petrels. As with the Terra-Gen project, bird strikes from the massive rotating turbine blades are a major concern.

Diagram of a wind turbine from Principle Power.

Shore-based development will have its own set of impacts. Redwood Marine Terminal 1, former site of the Hammond Lumber mill in Samoa, is being considered for redevelopment to host the shore-based component of any wind farm project, include massive warehouse space. Kalt noted that the location is vulnerable to sea level rise, and Baykeeper is concerned about soil contamination onsite.

Ogan said there’s also reason to worry about the impacts of shoreside development on Humboldt Bay’s eelgrass, which is important to Pacific black brant.

The potential wildlife impacts don’t end there. Sandy Aylesworth, an ocean advocate with the National Resources Defense Council, said in a recent phone interview that floating wind farms, with their arrays of undersea electric lines and anchor cables, may lead large baleen whales to avoid the area entirely. Marine mammals and sea turtles could get entangled in those lines or in ensnared debris, such as fishing gear. And the platform anchors could may scour the sea floor, causing sedimentation and destroying habitat in the benthic zone.

The Schatz Energy Research Center has been studying the potential environmental impacts along with numerous other aspects of the proposed offshore wind development, including economic viability, port and coastal infrastructure, electric transmission and interconnection, a policy analysis, seismic hazards and more.

With funding from BOEM, the California Ocean Protection Council and the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, among others, Schatz has been busy conducting three wind energy studies simultaneously, though they’re intended to function as a single, coherent analysis.

“The analysis we’re doing is important, but it will be important to do more,” Jacobson said. “That’s why we think a strong research agenda is important. It’s an enormous opportunity with huge potential to contribute to our region as well as California’s environmental and clean energy goals. But we need to treat it cautiously and do all the right due diligence to understand if it’s something we want to do at a significant scale.”

Jacobson and others are a bit worried about the public process after seeing some of the vitriol and distortions that accompanied debate over the Terra-Gen project.

“As we’ve seen, our community knows how to stop a project if it’s not favorable from a local perspective,” he said.

Richard Engel, the director of power resources at RCEA, said he, too, is worried after the Terra-Gen decision.

“I would say, candidly, I have concerns about the chilling effect, not just of the decision but also the tone that the public process might have on renewable developers in general,” he said. RCEA staff has stayed engaged with wind energy developers, trying to put the message out there that Humboldt County is not unfriendly to such projects, Engel said.

RCEA and its renewable energy company partners are hoping to secure a lease and build a project in the 100-to-150 megawatt range, big enough to provide a demonstration of commercial viability. The agency hopes to purchase some of the energy generated to serve local customers, though Engel said it would be “the caviar in our energy portfolio” due to its expense. The bulk of energy generated would be sold outside the area, which, again, will require significant transmission upgrades.

The researchers at Schatz hope to have a final report for its wind study ready to deliver to BOEM by May. At that point, Schatz plans to hold a day-long public workshop, releasing a host of data and getting feedback from the public and representatives of various agencies.

“My hope is that we can have a thoughtful, open and respectful discussion about this as a community,” Jacobson said. “The discussion around Terra-Gen did not live up to that. We need to find a way of doing better from a public conversation perspective.”

Determined critics will have no problem finding ammunition for their arguments, as Environmental Protection Information Center (EPIC) Executive Director Tom Wheeler told the Outpost. “In this age of easy information that we live in, you can nitpick a project pretty easily through a couple minutes on Google,” he said. “That’s one of my concerns on this project.”

For example, Principle Power, one of RCEA’s corporate partners, has ties to Royal Dutch Shell, an oil industry giant. Wheeler said our community may do well to look past that.

“Until we come up with that alternative capital funding structure, to some extent we have to plug our noses and realize rich people will become richer by serving a fundamental human need, which is to provide power,” he said. While he, for one, is all in favor of dismantling capitalism, he said the planet’s ecosystems can’t wait for that. “I don’t want to base climate action on a Marxist revolution,” he said.

Meanwhile, stakeholders have made a point of including tribal representatives in deliberation and planning processes. BOEM’s renewable energy task force includes not only Ganion, from the Blue Lake Rancheria, but several members of the Yurok Tribe. At the wind energy hearing in May, Shirley Laos of the Trinidad Rancheria underscored the importance of tribal ecological knowledge, saying, “Early and quantitative consultation is essential.”

RCEA Executive Director Matthew Marshall said his agency’s goal is to have a project online perhaps as early as the end of 2025, assuming everything goes smoothly. There’s a lot of scientific analysis and public discussion to be done between now and then.

Wheeler said the environmental review process will be extremely important. “But it’s also important that we recognize that with climate change, there will be competing values at play. We need to recognize there will be site-specific impacts, but there will be globally significant cumulative impacts by our failure to act on climate change.”

Small-scale efforts like rooftop solar panels are an important but insufficient, he added. “We need some sort of industrial scale renewable energy project, and if not this offshore project, I don’t know what it is.”

CLICK TO MANAGE