Migrants at the Pro Amore Dei Shelter in Tijuana. “The image of these lovely people completely contradicts the words the current American president uses to refer to them,” volunteer Maureen McGarry says. “They had warm, kind faces, and looked ready to work and contribute as soon as they had the chance.” | All photos courtesy Maureen McGarry.

Last July, local watercolor artist Maureen McGarry was among the crowd gathered at Fortuna’s Rohner Park for a vigil supporting detainees at the U.S.-Mexico border, and after listening to heartfelt speeches about the struggles of migrants and refugees, she felt frustrated.

“I came home and felt like I hadn’t really done anything,” she told the Outpost on Monday. Distraught by news stories about immigrant detention centers, children in cages and family separations at the border, she began researching volunteer opportunities.

“With all the media hype around this issue, I knew I needed to see firsthand what was happening,” McGarry wrote in a blog post last summer. “I wanted to help in person and be able to report back to my community the reality of that experience, and maybe encourage others to get involved. But no United States detention centers were allowing volunteers inside any of their facilities.”

Googling eventually led her to Border Angels, a nonprofit based in San Diego that focuses on migrant rights, immigration reform, and the prevention of immigrant deaths along the border. (The group has gotten some news coverage for its “water drop” program, in which volunteers leave bottled water, clothing and/or first aid supplies in remote areas along the border, hoping to prevent some of the thousands of deaths that occur among people trying to enter the United States.)

She reached out to the organization and learned about a program called Caravan of Love, which aims to help migrant asylum seekers who’ve been denied entry into the United States and are being held in Tijuana shelters.

Organizers told McGarry she was welcome to join one of these caravans, and they sent her a list of materials detainees need, including dry goods, underwear and hygiene products such as toothpaste. She connected with friends and family who wanted to help, and in a matter of just a couple of weeks she was preparing for her journey south.

From her blog:

The City of Arcata heard of our plans and offered to set up a table inside City Hall for donations. The community generously responded. We were able to collect a mountain of supplies in two days. Local businesses like Tin Can Mailman and SCRAP Humboldt donated books and art materials. People gave us money to pay for gas for the trip which added up to over $1,500.

Supplies collected in Arcata.

Before the month of July was over, McGarry crossed the border into Mexico with a Caravan of Love — 15-20 cars filled with volunteers, food and supplies.

“I asked if I could do an art project with the kids and they said ‘yes,’” McGarry said. “So I brought watercolors. I passed out the materials, watched them paint and helped when needed.”

McGarry wound up making three trips down to Mexico last year, and this week she and friends are headed down there again.

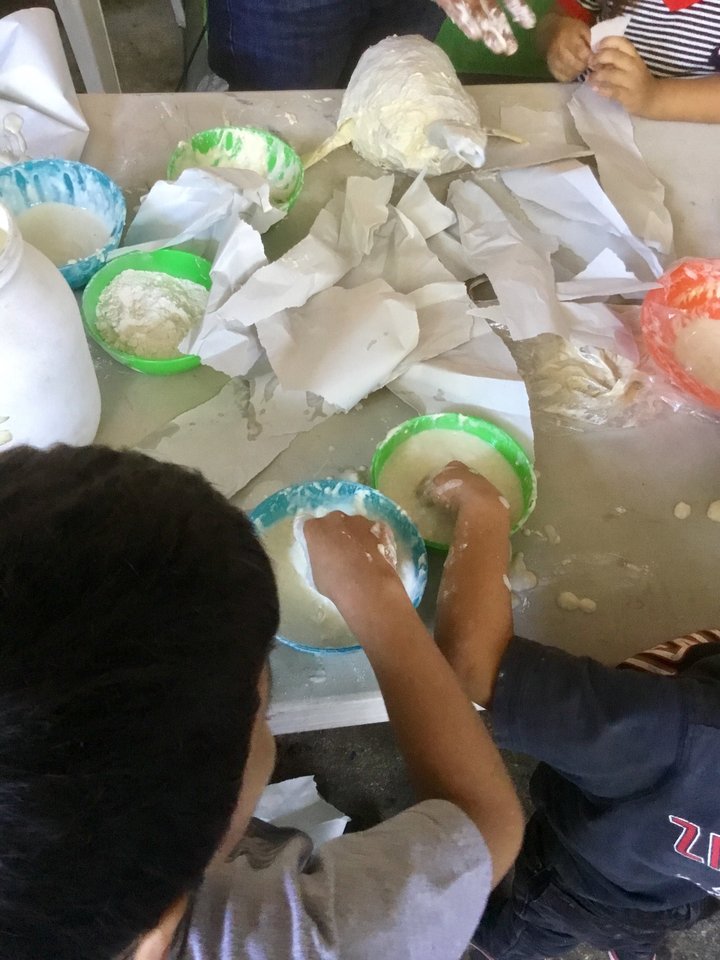

The hands of kids stirring up the flour-and-water paste for papier-mâché to build piñatas.

On her second visit she wanted to take on a more ambitious art project, so she brought materials to make piñatas — wire mesh, papier-mâché, paint. The shelters are mostly filled with women and children, McGarry said, families that have fled unrest in countries such as Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador.

The conditions aren’t as bad as what’s been revealed in U.S. detention facilities, but it’s still grim, McGarry said.

The Movimiento Juventud Shelter, located one block from the border wall. “Volunteer medical workers from San Diego are checking on everybody,” McGarry said. “This was the middle of summer. It was very hot.”

“The very first shelter we went into, the first thing that hit me was the heat,” she said. The shelter was the size of a small barn with corrugated metal walls and concrete floors covered with tents. “They were just packed in there.”

On her second and third visits, the piñata-making art project proved popular with both kids and adults. About a hundred kids gathered around — “more than I could really handle,” McGarry said. This was in a different shelter, a former church made of cinder blocks and metal roofing located in a community wrought with poverty. The shelter is set deep inside a ravine called Scorpion Canyon.

A young boy stands at the gate of the Embajadores de Jesus shelter in Scorpion Canyon, which was holding more than 100 children.

A pig chewing on some article of clothing caked with food from a burning garbage pit right next to the shelter in the canyon.

“Tijuana has [nearly] two million people, and a lot of them live in these canyons,” McGarry said. Most Americans, when they think of Tijuana, think Revolution Avenue, with its tourists, students, trinkets and bars. “But this part of Tijuana is definitely where poverty is right in your face — shacks in hillsides being held up by old tires, pigs and chickens running around eating out of old trash piles. It’s definitely not something we see in our sheltered lives here.”

But there in the shelter, making a mess with flour-and-water paste, people who’d suffered immense hardship suddenly seemed to be having fun.

A mom at the Pro Amore Dei Shelter, showing off the pig piñata she built.

“They were smiling,” McGarry said. “That’s the part that made me realize I have to keep going back. If you can bring that kind of joy to people who are basically stuck in this place, and they’re going to be there for a while, it was just really nice to see them smiling.”

Under the Trump administration’s Remain in Mexico program, it has become virtually impossible for migrants to win asylum cases in U.S. immigration courts. Tens of thousands of migrants have been told to wait in Mexico under this program, and for those who wait around long enough to get a court hearing, their chances of being granted asylum are less than 1 percent.

“We can’t forget that this is still happening,” McGarry said. “This will be part of our history, that we did this to these people. It’s something that we’re going to have to reconcile as a country — family separation and defying international law when it comes to declaring asylum. Our country has made up our own rules about it and as a result has caused a lot of people to live in very stressful situations.”

As she and some fellow volunteers head down again this week, they hope to alleviate some of that stress. While fun, piñatas proved a bit too bulky, so this time they’re bringing knitting and beading materials, along with the watercolors.

The ravine and dirt road leading into Scorpion Canyon. With higher levels of rain this year in Tijuana, much of the dirt has been washed away, leaving mostly big rocks and making the shelter difficult to access, McGarry said.

A migrant girl works on her Spongebob Squarepants piñata during McGarry’s most recent visit. “Many of the piñatas were inspired by American culture,” McGarry said. “Lots of Disney characters.”

CLICK TO MANAGE