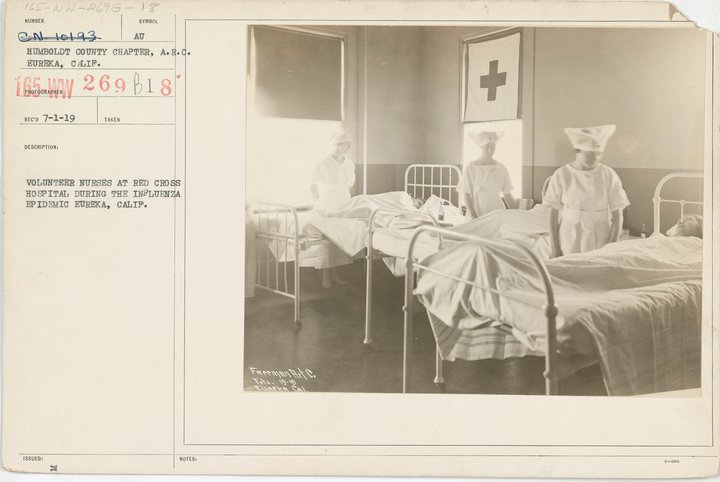

Volunteer Nurses at the Red Cross Hospital, AKA Northern California Hospital (National Archives)

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- Part 1: THE 1918 PANDEMIC: A Virus Comes to Humboldt

- Part 2: THE 1918 PANDEMIC: How Humboldt Tried to Slow the Spread

###

Do not call the doctors for information. They have just about all they can do without answering unnecessary questions as to whether you may take your child to the dentist; whether a certain out of town school will be closed; and whether the ice cream parlors are open.

– The

Humboldt Times, 22 October 1918

###

In July of 1918, two months after 19-year-old Imogene Lockwood started her nursing training at the Union Hospital in Eureka, she began a diary, realizing, she wrote, that the record would be invaluable “when age and ease have made my present view of life no longer possible.”

In early October of that year, Imogene was still learning how to balance classes, training and patient care when two Austrian travelers staying in Eureka fell ill with Spanish Flu and quickly infected their rooming house hosts. The next day five more cases were identified, and infection spread rapidly in Humboldt County from there.

By mid-October, local nurses and even students like Imogene were sick with the virus. The mayor of Eureka urged citizens to report suspected cases and local papers published guidance on how to avoid an “An Attack of Dread Influenza Germs.” Local physician Charles Falk did the same, warning that the flu was spread from person to person via “very small droplets” which could be spread by coughing or sneezing, forceful talking and more. Falk urged infected individuals to isolate and recommended that all nurses and attendants wear masks to protect themselves against the disease.

Despite the warnings, local case counts continued to rise, and area physicians grew frustrated, convinced area citizens were failing “to take the simple ordinary precautions necessary to avoid infection.” On October 19, the State Board of Health moved to close “all amusements” – including dances and movies – and local governments followed suit. Just the day before, Mrs. Ira Russ started building a list of individuals willing to help Humboldt’s patients. The list was a “precautionary measure,” Russ reassured prospective volunteers, and the workload would be light.

Instead, patients were transferred from outlying areas to Eureka’s hospital and the patient count quickly topped 100, taxing nurses and doctors. Officials moved to limit transfers and dedicate the Northern California Hospital exclusively for isolation of influenza cases, which would allow fewer nurses to care for more patients in one location. The arrangement stalled, however, when hospital owner Dr. Falk demanded $1,000 a month for use of the empty facility because of its “perfect condition.” Falk didn’t “care to have it filled with contagious disease” but would be willing to bend if the county could meet his price.

At this time, the local Red Cross Committee on influenza assembled a corps of nurses and emergency housekeepers for homebound patients and when the office in San Francisco issued a call for Home Defense nurses, local officials denied them, as all were “urgently needed here.” Organizers also asked “every woman” available to help support overworked nurses. In response, Miss Helen Kramer ran errands in “an auto” and Miss Dorothy Notley provided emergency housekeeping and cooking. Others served as able and volunteer coordinator Mrs. Russ vowed to “get assistance to every case possible which the doctors find in need.” When called upon, at least twenty-five volunteers showed up at the Red Cross office to make flu masks.

On October 20, Dr. N H. Bright, president of the State Board of Health’s predicted “waning” of the flu the same day Humboldt County announced its first flu-related fatality, and in the next few days more local nurses and doctors fell ill. The city of Eureka ordered those serving the public to wear masks and officials reached an agreement to lease Falk’s hospital. Health Officer Dr. Mercer also urged small towns, lumber camps, and other centers of population to follow Scotia and Samoa’s lead in establishing smaller, temporary flu hospitals in their communities to relieve the burden in Eureka.

The Red Cross drug store shut its doors because all employees were sick and local doctors received word that medicine from San Francisco would not be coming due to high demand. Dr. Mercer begged community members to stop congregating in the downtown districts.

As case counts grew, nurses like Imogene had to fight their own fear of the virus. On October 23 after falling ill, Imogene admitted that she was “almost a coward,” and contemplated giving up nursing so as to “not ever hear of germs again,” but she conquered her fear and went back to work, only to relapse just two days later. To her diary she confessed that she was “pretty frightened” and feared her mother and her brother might get sick. At that time, at least seven other nurses were also “down” with the flu.

To help address the nursing shortage, the Red Cross, with Mrs. Russ in still charge, worked quickly to get the Northern California Hospital up and running, outfitted with donated linens and furniture. Within days the facility had 23 cases and could accommodate more than 50. The kitchen was up and running and a number of women throughout town were preparing and donating food. The county librarian managed the hospital office, the requests for assistance were met with the “heartiest cooperation” and the women of Eureka were “finding more ways than those suggested” to be of assistance. When Anne Fenwick arrived from San Francisco to visit her parents, she spent a full day driving a car for Red Cross hospital managers, running errands and collecting supplies, and “was even prepared to move patients if necessary.”

By October 25, Eureka’s officials thought they glimpsed the end of the epidemic and attributed it to “the wearing of the masks and the splendid cooperation of the people in every way,” but the number of cases being treated at the Red Cross hospital continued to rise. The hospital stopped admitting visitors, but volunteers were still needed, and one thankful hospital committee member noted that there seemed “no limit to the response of the citizens” to help whenever difficulties arose.

On October 28, when “only 20 new cases” were reported for the day, Dr. Wing expressed hope that infections were decreasing, believing that anti-flu masks had cut “the sway of the malady short.” To support this belief, Wing pointed to reports from Mare Island, where nurses adopted masks early and with no other precautionary measures, not a single nurse fell ill.

Unfortunately, the number of cases continued to fluctuate. Fortuna established an emergency hospital at the Firemen’s Hall at Newberg and the Red Cross also took over a lodging house to care for patients in Arcata.

Fatalities continued, and doctors and nurses felt the strain as they fought their fears and cared for patients. On November 1, Imogene visited her mother but stayed on the porch, feeling like “some sort of pestilence.” Dr. Mercer, exhausted from “overwork” was forced to take time off and Miss Murial MacFarlan, who took over as Acting Health officer when Dr. Mercer fell ill, suffered what was believed to be a nervous breakdown “due to overwork.”

Union Labor Hospital (Humboldt State University Special Collections)

By the first of November, the Union Hospital was down ten nurses and Imogene, whose health improved, was thankful to volunteers who took over “everything but the actual nursing.” Local papers recognized the “valiant work” being done and many lives saved through the effort of local volunteers, though some, like J. F. “Buck” Buchanan, who was “on call wherever and whenever needed,” also fell ill.

By mid-November, the county was sadly losing nurses, but some, like Miss Neska Alexander, recovered and went back to work. Retired nurses were asked to “come forward as a matter of patriotism,” but younger women were discouraged from volunteering, in part because they were considered more vulnerable to the virus.

Physicians and officials implored the public to follow health recommendations, wear a mask and socially distance. If not, Dr. Mercer believed the disease would continue to spread and the “toll of death” would rise. Thankfully, many heeded the warning. On November 11, while Imogene Lockwood and others recognized the end of the war, their celebrating was “tame and hampered” due to grief over losing fellow nurses and their inability to see the “merry smiles behind a mask.”

Growing compliance with the mask ordinance was credited with a decline in cases in Eureka, but cases continued in outlying areas. Arcata was forced to repurpose the Women’s Club House into a Red Cross Hospital and officials toured the county to encourage adherence to safety measures. Eventually case counts started to fall throughout the county and by November 17, temporary “isolation” hospitals, like the one in Scotia, were able to close. The Red Cross hospital in Eureka shuttered its doors when the last patient was discharged on November 20. After fumigating the building with formaldehyde, which “not even the most hardy and tenacious bug known to science” could survive, it was turned back over the Dr. Falk.

Over the next few months, the flu resurfaced throughout the county, but it never again reached the extremes faced in October and November of 1918 when countless residents fell ill, and many died. Undoubtedly many more were saved thanks to the tireless efforts of health care workers and volunteers.

On Jan 1, 1919, with the trauma of the epidemic behind her, nursing student Imogene Lockwood wished her diary a “Happy new year!” She also resolved to study, put her profession first, guard her tongue and strive to be more cultured and refined. She and the other students faced extra work because of the time they lost caring for flu patients, but by 1922, Miss Imogene Lockwood and many of her classmates were registered nurses, caring for patients right where they had trained – at the Union Hospital in Eureka.

###

NEXT WEEK: The impact of the Spanish Influenza Epidemic on education, religious services, jails, and the business community.

###

Lynette Mullen writes about Humboldt County history at Lynette’s NorCal History Blog.

CLICK TO MANAGE