Dr. Teresa Frankovich | Courtesy of Humboldt County

###

Humboldt County confirmed its first case of COVID-19 on February 20, just about a week after the new disease was named. At exactly 1:58 p.m. that day, Dr. Teresa Frankovich, the county’s public health officer, sent an email alerting staff to the confirmed case in the county and to another potential case.

Frankovich had become aware of the first two possible cases around February 16. She had reached out to the California Department of Public Health to seek advice on how to proceed after receiving approval for testing from the Center for Disease Control. She was told to collect nose swabs and lower respiratory specimens from patients with productive coughs. The specimens were collected and shipped overnight to Atlanta, and a few days later Frankovich received the results and alerted staff.

“I got off the phone at about 1:10 from [the] initial state notification call and within [three] hours, info went out to media and providers, hospital was notified and given direction, staff had contacted the patients and all were back on a conference call with [the] CDC and [California Department of Public Health] at 4:15 for further instruction,” Frankovich wrote in an email sent at 11 p.m. on the night of Feb. 20, recapping the day’s events.

At the beginning of the pandemic, communication between public and private entities was a bit mismatched. The county planned to issue its own press release about the new COVID-19 case, while officials at St. Joseph’s hospital planned to do the same. Those in charge were also a bit hesitant when it came to releasing information to the public, and even discouraged one of the first people tested from alerting their supervisors at the school district they work in.

A review of over 2,000 emails from Jan. 31 to March 12, obtained by the Outpost through a public records request, shows how county staff — in particular those in contact with Dr. Frankovich — prepared for the pandemic.

These emails show that there were a few bumps in the road while figuring out the response to the pandemic. But the impression they leave overall is that county staff worked tirelessly to combat the virus early on, with numerous emails sent on weekends and late into the evening.

Staff worked to improve the amount of personal protective equipment it had in stock and to increase the number of nurses fit-tested for that PPE. It outlined how contact-tracing should be done and tried to figure out how to mitigate possible transmission from health care workers to patients. It did all this and more either before or within days of the first case.

In a recent interview with the Outpost, Frankovich said she couldn’t remember exactly when she realized that COVID-19 would turn into a pandemic. She said she relied on officials at the World Health Organization and paid attention to the debate about when COVID-19 would hit that defining mark. She also paid attention to what was happening throughout the state.

“Most people in public health were looking at the areas where this was emerging first, how it was unfolding, and became concerned about the pace of it,” Frankovich said. “I was certainly looking at the Bay Area and the surrounding counties to inform [my] decisions.”

Back in late February, Frankovich was sent a report titled “What US Hospitals Should Do Now To Prepare for a COVID-19 Pandemic,” from Jake Hanson of the California Department of Public Health. The report, written by Drs. Eric Toner and Richard Waldhorn, stated that COVID-19 was more severe than typical influenza pandemics of the past, and the impact on hospitals would be “severe in the best of circumstances.”

“Although a COVID-19 pandemic seems all but inevitable, there is still uncertainty about its severity in the United States. Time will tell, but, in the meantime, hospitals should not delay….” the report reads. “Several of the first priority items (comprehensive and collaborative planning, discussing allocation of scarce resources, and planning education and training) take substantial time. Hospitals should begin these actions now.”

And planning did start relatively quickly. Jeremy Corrigan, laboratory director and bioterrorism coordinator for Humboldt County, tried to get Humboldt on a list of 100 labs across the country that were doing testing. His efforts started in early February and included lobbying the California Department of Public Health to ask the International Reagent Resource, a branch of the CDC, to allow Humboldt County access to the necessary supplies to start testing locally. Corrigan’s efforts eventually got Humboldt on the list.

“The reason we are allowed to perform this assay locally, is because we have a track record as a lab of excellence, we have the right equipment and technical expertise to stand this assay up,” Corrigan wrote on Feb.6. “[CDPH] also would like our lab to have the assay due to our remote location, all great news!”

Before the first case was known, local officials also worked quickly to address the personal protective equipment in stock throughout Humboldt County. Sofia Pereira, public health emergency preparedness program coordinator and Arcata city councilmember, sent out a poll to nine local health facilities inquiring about their PPE stock in mid-February.

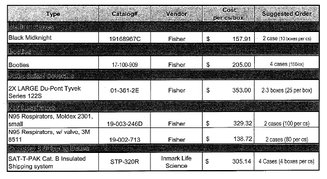

A photo of a receipt for PPE from Mendocino County.

The local cache ran a bit low at first and on Feb. 24, Humboldt County had to ask Mendocino County for help. Humboldt requested two cases of gloves, four cases of booties (600 pairs), two to three boxes of XXL Tyvek suits (50-75 total), 360 N95 masks, and four cases of insulated shipping materials totaling $1,331.21.

“Overall, I think we are in a much better PPE position,” Frankovich said. “One of the things in terms of moving forward is knowing that we have adequate PPE for at least two weeks at a time. We are having places like hospitals, skilled-nursing facilities and assisted-living facilities provide information on their ongoing cache of PPE, so we can understand if it becomes short or if they need additional support.”

Frankovich said the county would put in orders through the state to increase the local stock. She said the county also keeps a supply as a backup to distribute to local facilities if there is an immediate need. Local private health care facilities conducted mock drills to plan what to do in the event of person who suspects they have COVID-19 self-reports to their doors.

###

Contact tracing from the first case in Humboldt County revealed that four people were identified as “medium risk” and one was deemed “high risk” on February 24, just four days after the first patient was diagnosed. All identified contacts agreed to quarantine in their homes and food delivery arrangements were arranged for family members to bring needed supplies.

In a recent interview, Frankovich said that during contact investigations there are times when the infected patient’s employer will be notified if their diagnosis is relevant to their workplace and, at times, encourage them to speak openly about their situation. However, this seems to run contrary to what was found in a few emails obtained by the Outpost. It is not certain if the positive case and the five potentials were asked to stay tight-lipped about their situations, but one person who was awaiting test results was discouraged from telling the school district representatives where they worked about their quarantine status.

A screenshot of an email from Erica Dykehouse to her colleagues.

Erica Dykehouse, communicable disease and tuberculosis prevention nurse with Humboldt County Public Health, detailed the following on Feb. 24:

1 of the quarantined individuals shared with close friends who visited recently that they are being quarantined out of a sense of duty. This created a bit of a stir Friday when one of those friends then shared with their employer that they were a contact to a quarantined contact to a confirmed case of COVID-19.

The second household member of that household wanted to also advise their direct supervisor and several others they work with in a school district of their quarantine for the same reason. Erica discouraged this on Friday explaining the sense of alarm this would cause despite our intention. We will develop a better plan for disclosure to employer with the contact if she wishes to do so.

The high risk contact to the confirmed case advised her employer that she would need to stay home because she was being quarantined due to her recent travel. After reading the news, employer has assumed that her employee is either the confirmed case or the suspected second case. Daily conversations with contact to help manage anxiety related to this.

Confidential information related to the confirmed case was posted on Instagram on the night of 2/20/2020. This information was relayed to Erica by text by the high risk contact. Dr. Frankovich has brought this to the attention of Roberta at SJH.

When later asked about why county staff would discourage an individual from alerting their supervisors at a school district, Frankovich said that this is not a regular practice, per se — rather, the department encourages patients to limit information to those who need to know it. In the instance of the individual who worked at the school, Frankovich said they ended up speaking with their supervisor and that “there was absolutely no risk of workplace exposure.”

“If there is any possible relevance to the workplace then it has to be discussed,” Frankovich said, adding that family members should follow similar quarantine procedures. “With close contact, and usually household members are considered a close contact, those individuals are quarantined and [they] should remain home except for accessing medical care.”

In the days after the first case, even the city in which these individuals were quarantined stayed confidential. First District County Supervisor Virginia Bass asked if the County could share what city the first patients were located in in a Feb. 24 email. If the county couldn’t share this information, Bass asked, why not?

Frankovich responded by saying since Humboldt County is a small rural area, even disclosing the city could jeopardize the identity of the patients. “I understand community concerns, but there is clearly a difference between wanting to know and needing to know,” Frankovich wrote to Bass. “In future events, if there is ever an actual need to know towns of residence in order to help us identify people at increased risk, that information would be shared.”

###

The thought of declaring COVID-19 a countywide public health emergency seems to have first been brought up by Scott Adair, the county’s director of economic development, when he forwarded Mendocino County’s declaration to County Administrative Officer Amy Nilsen, who then forwarded it to several county staffers.

“Is this something we should be exploring?” Nilsen, Humboldt’s county administrative officer, asked in a March 5 email to her colleagues.

Public Health Director Michele Stephens then forwarded the email thread to Frankovich later that morning, bringing to her attention that counties across California are starting to declare COVID-19 an emergency.

“In the very near future we will be reaching serious capacity with managing calls and testing requests, so I think at this point we might as well, it will happen eventually so why not now. But open to your thoughts,” Stephens wrote to Frankovich on March 5.

Frankovich — who had been in the job only a little more than a month —responded by asking if declaring such an order was within her duties as a public health officer, to which Stephens replied that this had been her experience, and used a past order issued during a fire as a template. Stephens said the declaration of an emergency goes before the Board of Supervisors as well.

Stephens asked Sofia Pereira to look other counties’ declarations. Pereira found Sonoma County’s declaration, which was issued on March 2, enacted this preemptive action due to evidence from the WHO that COVID-19 was a public health emergency on Jan. 30. It cited the virus’ spread across China and a CDC determination, among other reasons.

“Conditions of extreme peril to the safety of persons and property have arisen within [Sonoma] County caused by the threat of COVID-19 that will impact significant County and community operations, including critical public infrastructure and services, and which will require the provision of additional public safety and emergency services,” Sonoma’s order stated.

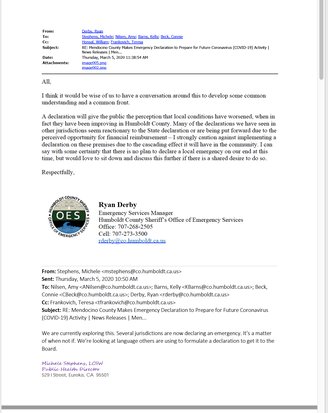

However, Ryan Derby with the Sheriff’s Office’s Office of Emergency Services said he would like to have a conversation about issuing such an order and ultimately cautioned against it.

A screen shot of an email from Ryan Derby to Public Health and other County staff.

“A declaration will give the public the perception that local conditions have worsened, when in fact they have been improving in Humboldt County,” Derby wrote on March 5. “Many of the declarations we have seen in other jurisdictions seem reactionary to the State declaration or are being put forward due to the perceived opportunity for financial reimbursement – I strongly caution against implementing a declaration on these premises due to the cascading effect it will have in the community. I can say with some certainty that there is no plan to declare a local emergency on our end at this time.”

But Frankovich issued a local health emergency declaration just five days later, and the Board of Supervisors signed off on it at its March 17 meeting.

In a recent interview, Frankovich said that declaring the order helped to solidify the messaging going forward.

“I think it really did take having the [Emergency Operations Center] in place to be able to make the messaging more robust,” Frankovich said. “Once we were able to provide ongoing messaging and information, it probably became less necessary for some of the other places, like the hospitals, to try and do that.”

###

Another concern early on came from local hospitals and how much time they were contributing to testing people coming in. On March 12, May Riley, an employee at St. Joseph’s Hospital, wrote to Dr. Roberta Luskin-Hawk and cc’d Frankovich with the subject line “Both Emergency rooms need help.”

She said there were increasing demands on the emergency department for COVID-19 testing to be done and ultimately urged the county to set up its own testing center because local business owners were urging their employees to get tested before coming into work.

“Their employers ask them to be cleared before their bosses allow them to return to work. These people have very minor symptoms,” Riley wrote. “Some of these people contacted their primary care providers but their PCP asked them to come to our [emergency department].”

Riley went on to detail the volume of calls coming in, stating that by 1 p.m. on March 12 Redwood Memorial Hospital had received three calls requesting COVID-19 tests. St. Joseph’s Hospital had received 10 calls and three walk-in requests. Riley urged the county to set up its own testing facility. Daniel Kelly, the interim chief nursing officer with St. Joseph’s, concurred.

“The county should set up a testing center in a tent with walk-in and done through capability. This referral by employers or county should not be driven to our [emergency department], as it will create huge capacity issues,” Kelly wrote.

The testing burden was eventually relieved on April 28, when the county opened its own testing center.

Moving forward, Frankovich said recently, testing will play a key role in understanding how the virus interacts with the public. The county now has plenty of tests to meet the demand and she urged the public to get tested at least once a month.

“I think currently we are seeing a drop-off in the number of people being tested, but I would love to see more because it provides that denominator we need,” Frankovich said. “For us to be able to really monitor how much is really out there, we need to test a broad swath of our population and to do that in an ongoing fashion.“

The testing will help monitor the current situation and allow officials a look into what is to be expected in the fall.

“If you look at some modeling projections now they would say fall or late-fall would be a potential time for surge, but with our relatively small case count, the models are pretty rough,” Frankovich said.

Just this week Humboldt has experienced a surge in cases. As the economy continues to open up and people start to move around more, Frankovich said there remains a need for the public to remain vigilant about COVID-19. In an address to the public on June 24, Frankovich said she understands that people have grown tired of the pandemic, but there still needs to be action. Combating the spread of the virus entails taking preventive measures to mitigate spread and being able to monitor its progress.

“So that is why for small areas like ours, I think it is incredibly important to have a lot of testing done for surveillance,” Frankovich said “so we can really monitor in real time.”

###

DOCUMENTS

County staff emails about the novel coronavirus and COVID-19 sent between Jan. 31 and March 12, obtained by the Outpost via a public records act request:

CLICK TO MANAGE