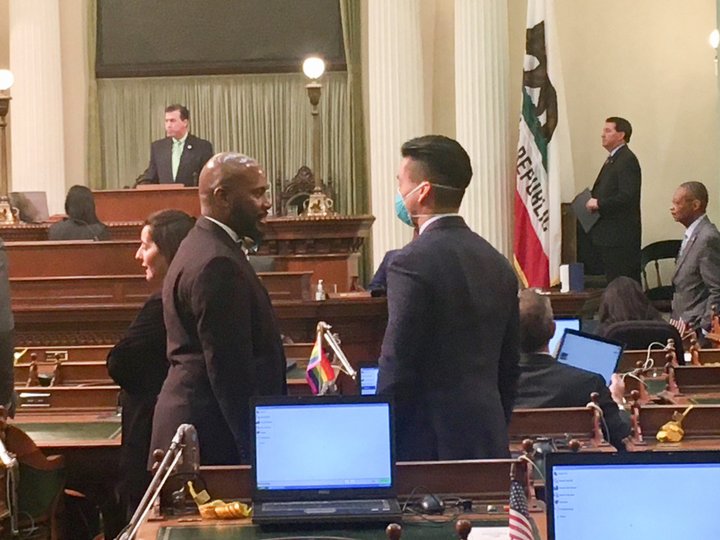

Assemblymember Evan Low wears a protective mask on the floor as lawmakers gather to address the coronavirus emergency. Photo by Laurel Rosenhall for CalMatters

###

In an urgent attempt to prepare California for a surge of critically ill coronavirus patients, state lawmakers Monday allocated up to $1 billion for an unprecedented ramp-up of hospital capacity, and then, in an extraordinary move, sent legislators home for a month — or perhaps longer — effectively shutting down business at the state Capitol as Americans face growing calls to isolate themselves.

The move to adjourn until April 13 came as states across the nation enacted sweeping measures to stem the fast-moving pandemic and the nation’s economy began to shut down. Stocks tanked. President Donald Trump — who for weeks downplayed the danger as a “hoax” no riskier than an ordinary flu season — said the nation “may be” on the verge of recession, triggered by an outbreak that could last into the summer.

In a conference call with governors, the president also said that states should not wait for the federal government to get them the respirators and ventilators that health officials say will be desperately needed if the United States follows the trajectory of other nations overtaken by the virus, such as China and Italy.

“Respirators, ventilators, all the equipment — try getting it yourselves,” The New York Times quoted the president as saying in a recording of the call.

In California — where the virus has claimed at least 11 lives, infected at least 572 people, and on Monday, left most of the Bay Area under a “shelter in place” order — lawmakers passed measures giving the state broad authority to spend up to $1 billion “for any purpose” related to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s declaration of the coronavirus emergency.

That declaration expedites the government’s ability to procure goods and services to mitigate the effects of the virus, and lawmakers said the money would be used to expand capacity in California hospitals, add beds in health care facilities around the state and buy hotels and motels to shelter sick Californians who lack homes.

They made $500 million available immediately and allowed Newsom to spend up to $1 billion total, passing two bills with warp speed by waiving a requirement that legislation must be in print for three days before lawmakers can act — a rule that can only be scrapped during an official emergency. They allocated an additional $100 million to California schools, to do a deep disinfecting of campuses, and passed a law granting schools full funding despite the prolonged closures.

Lawmakers put partisanship aside and passed the spending measures unanimously.

“We are placing an extraordinary degree of trust in Gov. Gavin Newsom,” said Republican Assemblyman Jay Obernolte. “However these are extraordinary times… These funds are critical to making sure our infrastructure is built up to deal with this emergency.”

“California is in a critical period for flattening the transmission curve for COVID-19,” said Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins, “if we are to prevent our health care systems from being overwhelmed.”

“We are placing an extraordinary degree of trust in Gov. Gavin Newsom,” said Republican Assemblyman Jay Obernolte. “However these are extraordinary times.”

The actions indicate that California is preparing for a worst-case scenario if the virus can’t be contained: a medical system without enough beds or equipment to serve a burst of critically sick people.

Newsom said that California right now has only about 74,000 hospital beds, including 11,500 intensive care unit (ICU) beds. It also has “surge capacity” of 8,661 more beds,” and about 7,600 ventilators in the existing hospital system, with perhaps 700 more as backup. Regardless of Trump’s suggestion, the governor added, “the state of California is already ahead of the curve” in procuring ventilators on its own.

The scope of the potential need isn’t entirely clear because U.S. testing has lagged severely, depressing the case count. But estimates based on the experience of countries already hit by the virus indicate 40 to 70 percent of the U.S. population could become infected in the next 18 months. Separate estimates for national worst case scenarios show that anywhere between 2.4 million to 21 million people could require hospitalization nationally.

A USA Today analysis that took into consideration the number of beds already in use found that California may need 20 times its number of open beds to handle a surge of patients.

To prevent that outcome, experts say Americans must “flatten the curve” of the epidemic, another way of saying slow the rate of spread. Under a flattened curve, many people get sick over a longer period of time, allowing the health care system to handle incoming cases. Under the opposite scenario — a steep spiked curve — there could be more sick people than hospital beds and ventilators.

Our #FlattenTheCurve graphic is now up on @Wikipedia with proper attribution & a CC-BY-SA licence. Please share far & wide and translate it into any language you can! Details in the thread below. #Covid_19 #COVID2019 #COVID19 #coronavirus Thanks to @XTOTL & @TheSpinoffTV pic.twitter.com/BQop7yWu1Q

— Dr Siouxsie Wiles (@SiouxsieW) March 10, 2020

In its most severe form, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome, where fluid floods the lungs. Patients with such severe disease need to be placed on ventilators in order to breathe, and can take between two to three weeks to recover, according to John Balmes, a professor of medicine and pulmonologist at the University of California San Francisco.

“Assuming they make it,” Balmes said. “Not everybody makes it.”

Balmes estimates that there are probably enough ventilators in the US — including back ups — to handle an epidemic that spreads slowly, keeping the curve of cases relatively flat.

“Much of the northern hemisphere needs ventilators, so there’s a big need, and, hopefully, an adequate supply,” Balmes said. “But ‘hopefully’ is the operative term there.”

“That’s why people are dying at such a high rate in northern Italy,” Balmes said. “They literally don’t have enough ICU beds and ventilators to take care of everyone who needs that care.”

But Balmes said he doubted that the country’s current capacity would hold up to a surge in cases like in Italy, where 2,100 people have died, including 300 people on Monday alone, The New York Times reported.

“That’s why people are dying at such a high rate in northern Italy,” Balmes said. “They literally don’t have enough ICU beds and ventilators to take care of everyone who needs that care.”

In Wuhan, China, doctors had to decide how to allocate 600 ventilators to the 1000 patients who needed them, The Washington Post reported. It’s too early to say whether California will see the same surge. That’s where efforts at social distancing come in. “The whole point of our current public health strategy is not to prevent community spread, because it’s too late for that — but to slow the community spread,” Balmes said.

On Sunday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom advised seniors older than age 65 and those with chronic health conditions to stay home. And on Monday, people in six hard-hit Bay Area counties — San Francisco, Santa Clara, San Mateo, Marin, Contra Costa and Alameda — as well as Santa Cruz were ordered to shelter in place “except for essential needs.”

“Hopefully it’s not too little too late,” Balmes said. “We’re going to have to see.”

To some extent, hospitals say, they have prepared for a potential surge in patients. Dignity Health spokesperson Joann Wardrip, for example, said Dignity has areas in each of its facilities where staff could care for infected patients in a tent or other annex and not expose the general population.

“If there were an influx of severely ill patients at one location, we would triage the most critically ill who need a higher level of care,” she said. “Patients could also be transferred to our sister facilities or to other nearby health systems.”

Some hospitals — Sutter and Kaiser Permanente, for example — also are postponing elective surgeries to make more beds available, or considering it. Also being pushed are telehealth and video appointments, which can keep people at home and save critical protective gear such as surgical gowns and gloves.

The national nurses union, which has been vocal about the shortage of equipment and what they view as inadequate staff training, however, has contended that existing measures may be insufficient, and has called for the reopening of closed hospitals, as well as barring any more hospital closures.

The city of Wuhan, China, where the virus was first detected, built two temporary hospitals to accommodate the influx of patients. Together, those hospitals made available another 3,000 beds.

Converting conventional hospital rooms into intensive care units would not be an easy task, according to Lee Riley, a professor of epidemiology and infectious diseases at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health. “They’re very highly specialized units that require a lot of renovation and equipment that are not easy to change,” Riley said.

Patients with respiratory failure on ventilators, for instance, require frequent monitoring of their heart and lung function. “If you have all these patients coming in requiring ventilators, where do you put them?” Riley said. Caring for patients on other floors, or outside in tents, he said, “It’s just tremendously expensive. It’s just a lot of people power, a lot of equipment, a lot of monitoring devices, a lot of testing.”

Makeshift hospitals are something states should definitely be thinking about, said Dr. Mahshid Abir, an emergency room physician at the University of Michigan and a policy expert at the RAND Corp., a think tank.

“This situation is fluid, and all indicates that we haven’t reached the peak of the pandemic, so we should be looking at all means of surge capacity,” she said.

She thinks states should be looking closely at their capacity for critical care. “There isn’t much wiggle room there because you need the ICU beds, you need the staff, you need the ventilators,” she said.

Other facilities, like hotels and motels are best for creating shelter for certain people, like those who need to be quarantined but don’t need medical care, she said.

###

CalMattters staff reporters Rachel Becker and Ana B. Ibarra contributed to this report. CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE