POTUS

(March 3): “So you’re talking over the next few months, you think

you could have a vaccine?”

Alex

Azar*: “You won’t have a vaccine…You’ll have a vaccine to go

into testing.”

POTUS:

“All right, so you’re talking within a year.”

Anthony

Fauci**: “A year to a year and a half.”

* US

Secretary of Health and Human Services

**

Director, since 1984, of the National Institute of Allergy and

Infectious Diseases

###

Antibodies— key components of the body’s immune systems—are the search-and-destroy blood proteins that detect and neutralize alien pathogens, such as harmful bacteria and viruses. In the case of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic), we have no natural antibodies, because until last November, no humans had been exposed to it. That’s why it’s called a “novel” coronavirus. To get immunity, you either have to be exposed to the virus (and survive!), or you have to be vaccinated against it. Hence the rush to develop a safe and effective SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

Vaccines work by exposing the human immune system to either a weakened live or a dead pathogen—in this case, a version of SARS-CoV-2 that will prompt the body to produce antibodies without causing harm. To both develop such a safe-but-effective vaccine, and to produce it in vast quantities, is a lengthy process fraught with missteps. Which is why—even though several candidate vaccines are already in the animal-testing stage, with a few dozen more on the way—it will take so long to get from a potential vaccine to one that’s commercially available.

(This isn’t just academic: in the 1960s, a vaccine against “respiratory syncytial virus” that causes symptoms similar to the common cold in children actually aggravated the symptoms in kids who caught it. Two died.)

Clinical trials for vaccines are non-random and random research studies on people to establish which candidate vaccines are both safe and effective. They typically run in three consecutive phases:

One: A few dozen healthy volunteers are given the candidate vaccine while checking for adverse results.

Two: Having established safety, several hundred people who live in a “hot zone” (where they’re likely to be exposed to the disease) are given it, to see if it works.

Three: same again, with thousands of people. This is when many potential vaccines fall by the wayside. “Our experience with vaccine development is that you can’t anticipate where you’re going to stumble,” writes Richard Hatchett of Oslo’s nonprofit Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, which is funding a broad range of both traditional and novel vaccine approaches for SARS-CoV-2. Phase three culminates in FDA approval.

Once a vaccine (or any drug) is approved, the process morphs from a science challenge to one of money and politics. Jonathan Quick, author of The End of Epidemics, writes, “Getting a vaccine that’s proven to be safe and effective in humans takes at best about a third of the way to what’s needed for a global immunization program.” Following approval, the vaccine needs to be manufactured in bulk, but it’s a long stretch from the research lab to quantity production. Big Pharma is interested in profits, not philanthropy—they make their money from repeat drugs, not from one-shot deals. And who gets the first batches? Hospital workers? Rich people and countries? Poor nations where it’s usually most needed? (Someone pointed out that India, a major vaccine producer, is likely to prioritize its own 1.3 billion people before supplying the rest of the world with a COVID-19 vaccine.)

So don’t hold your breath. Chances are, the pandemic will have peaked and be well on the decline by the time you can get your vaccine shot.

Wash your hands.

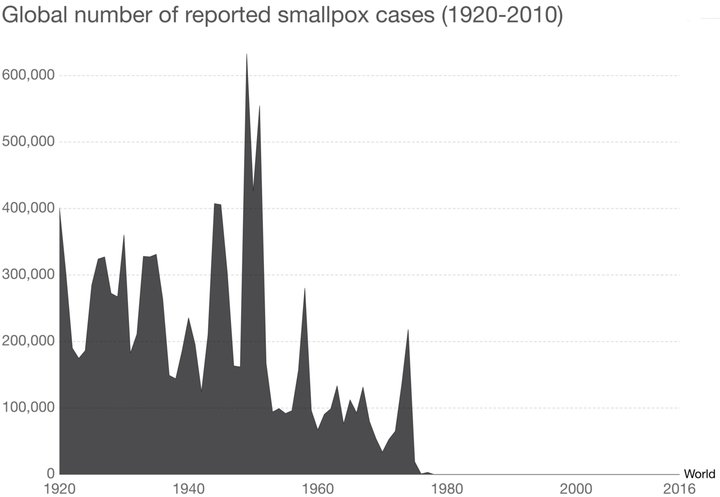

Vaccines work! Show this to any antivaxxer friends. Remind them that 80% of the 167 children who died of the 2017-2018 flu were unvaccinated. (WHO)

CLICK TO MANAGE