UPDATE, FROM THE EDITOR: Turns out Barry was trespassing, probably unwittingly. He’s an innocent fellow, and undoubtedly grew up scrambling over stiles in his native shire, where such behavior is tolerated.

Here in America, he may get gored! Here’s an email we got this morning:

The Pioneer Cemetery is surrounded by private land, as is the gate Evans is encouraging people to jump over. Visitors are welcome with permission from November 1 to May 1. There is a phone number they can call to have the gate opened for them. The surrounding area around the cemetery has been always been used for cattle and hay. When the cows are calving and bulls are on the property, it is unsafe for people to be walking around and the reason the gate is locked … Please notice in the comments there is a photo attached from Laura Cooskie letting visitors know of the correct and respectful process to enter the property.

Visitors may safely visit the cemetery without permission when the gate is unlocked and it is safe to do so, which is usually after May 1st till Nov 1st.

— Ed.

###

Someone

asked the Buddhist teacher Kyodo Roshi what happens after we die. “I

don’t know,” he said. “I thought you were a Zen Master?”

“Yes, but not a dead one.”

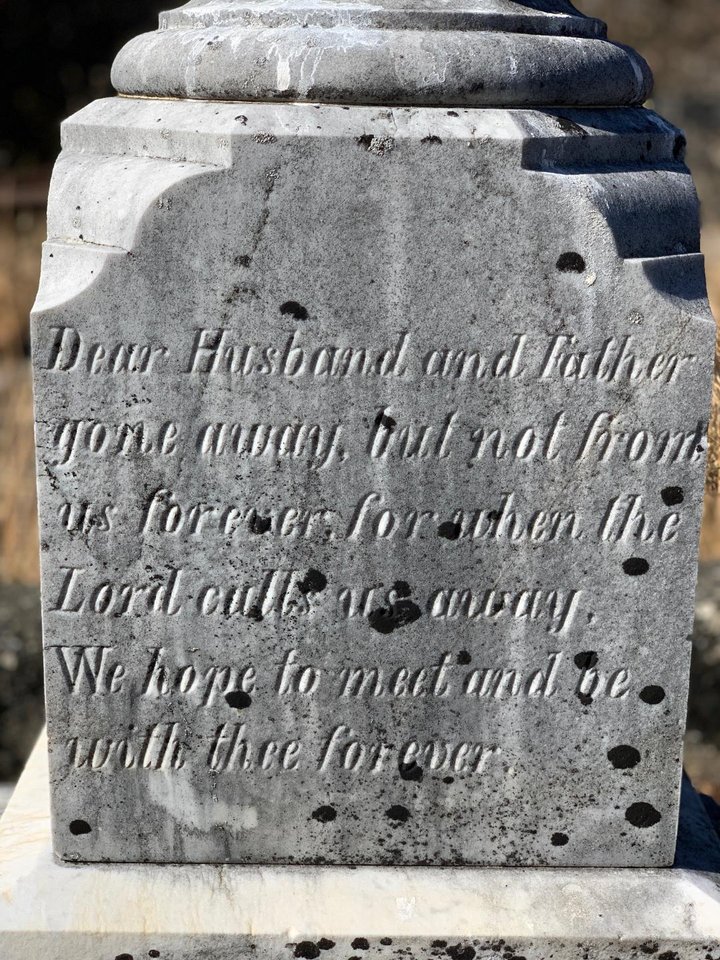

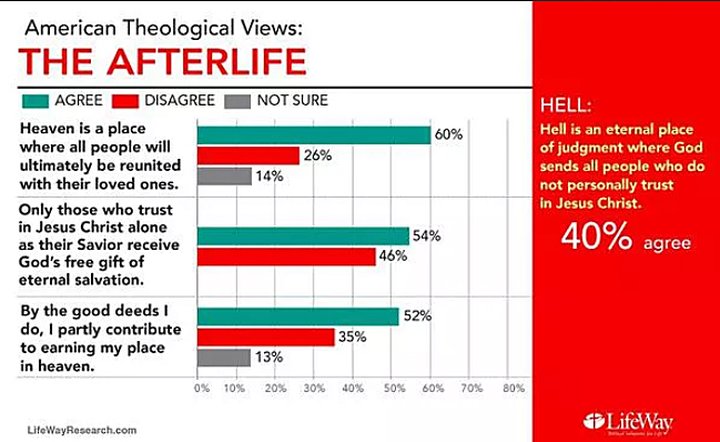

“We hope to meet and be with thee forever” is the engraved sentiment of the wife and children of a long-dead settler, according to a headstone in the Petrolia cemetery. Nothing unusual here—it echoes the common belief of Americans at the time, some 150 years ago. In our own day some 60% of us think we’ll be reunited forever with our loved ones after we and they are dead. For many, this is a great consolation: life here on Earth may suck, but be a decent person, play your cards right, and your heavenly reward awaits.

LifeWay Research, 2016

For materialists like myself, there’s the problem of what it is, exactly, that ends up in the great hereafter: a cloned body, fresh, young and cancer-free, while your corpse lies a-moldering in the grave? Or a sort of ghostly being with all the attributes and memories of the original being that’s able to swish around merrily in the Elysian Fields? Can spirits drink spirits? Can they enjoy a bowl of fettuccini Alfredo? Do they poop?

(I’m no theologian—obviously. For answers to these, and many more afterlife conundrums, you’ll have to consult Augustine of Hippo, who figured all this out nearly two thousand years ago: “”The bodies of the saints, then, shall rise again free from blemish and deformity, just as they will be also free from corruption, encumbrance, or handicap.”)

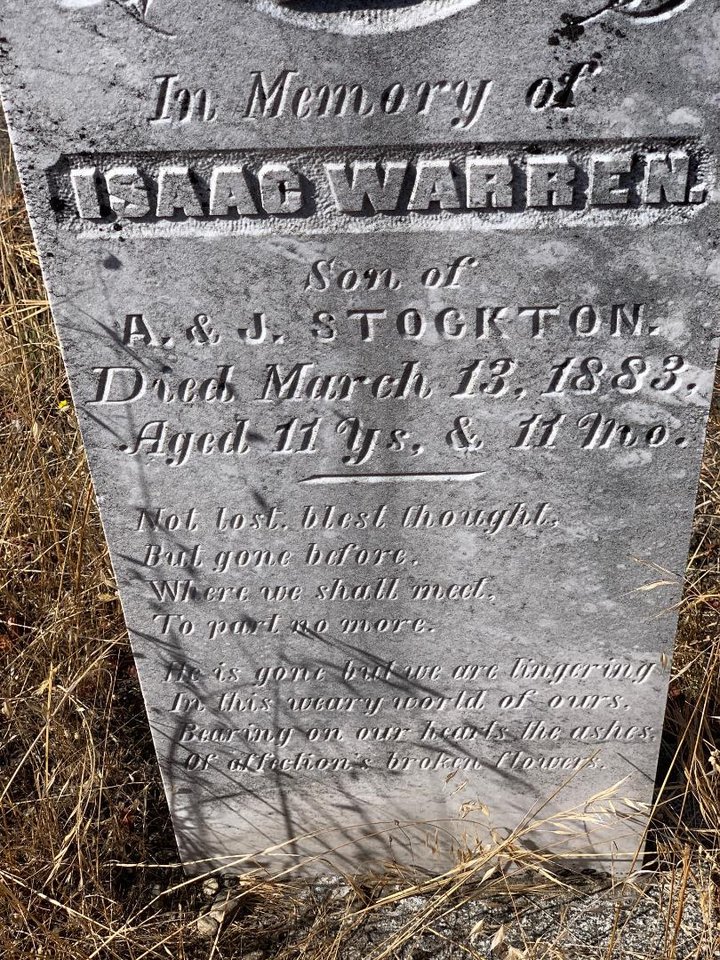

There’s another problem, though, the “forever” bit. Forever’s a long time, as I understand it. (“…gone before, Where we shall meet, To part no more.”) What I’m wondering is, has the pandemic changed anything for heaven-bound believers? In the enforced confines of social distancing, are those of us blessed with mates finding them ever more wonderful and entrancing as days lengthen into months? Or are we perhaps, not to put too fine an edge on it, having second thoughts about spending all of eternity, year-in-year-out, forever, with one particular soulmate? After a few thousand years, might those endearing little idiosyncrasies—forgetting what they were saying in mid-sentence, the way they floss their teeth in front of you, putting the toilet paper on the roller the wrong way—start to irritate?

We can’t, of course, imagine eternity, any more than we can imagine infinity. All we’ve got to go on is the sense of our own brief histories, while we struggle to appreciate what true history actually is. I can sort of get my mind back to the Second World War (having been born in 1942) and I think of my dad who was 10 in August 1914 and who had a vivid memory of seeing, in huge letters outside the local news-agent shop in his Welsh home town, one word: WAR! Beyond that, it’s just a blur of dates and eras. I teach an occasional OLLI class on the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the oldest being the pyramids of Giza, of course, nearly five thousand years old. But I can’t feel those five thousand years, any more than I can feel the three-plus million years ago when Lucy lived in present-day Ethiopia. But millions of years are nothing—literally—compared to eternity.

All these thoughts came, unbidden, in the Petrolia cemetery last week. We usually visit it when we’re in the Mattole—it’s a seven-minute walk west of the store, including clambering over a gate. The stones tell stories of the old-timers who found their way there over a century ago, a time when lifespans were measured, not just in years, but down to days: Lille May lived just 15 years 8 months 22 days. (“Weep not Father and Mother for me, For I am waiting in glory for thee.”)

At the entrance to the cemetery there is, incongruously, a US Mail box. No, not for letters mailed to those inside, as I idly wondered. Instead you’ll find, along with the guest book, a fascinating record of everyone buried here—who they were and where they came from. Talk about a time machine to the past!

And if an hour spent wandering and ruminating among those stones and monuments doesn’t inspire you to carpe diem, ready to urgently appreciate whatever time you have left (years, months, days) of your flesh-and-blood existence in this imperfect world, I don’t know what will.

CLICK TO MANAGE