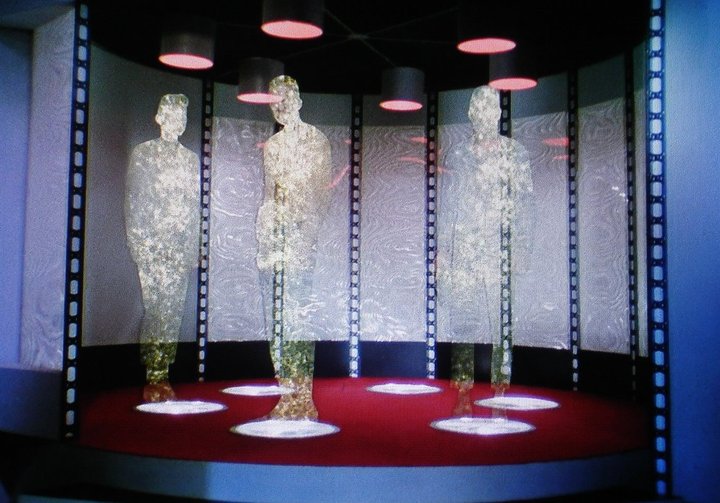

I signed on this ship to practice medicine, not to have my atoms scattered back and forth across space by this gadget.

– Dr. McCoy, on the Transporter

###

Last week’s riff on the impossibility of time travel* brought up a couple of basic snags that can equally well be applied to teleportation. I think we all know about teleportation, having seen it at work, usually flawlessly, as USS Enterprise crew members are beamed away from, and back to, the Transporter room, with barely a “Beam me up, Scotty” line out of place. (Yeah, I know. Same with “Play it again, Sam” and “Toto, we’re not in Kansas anymore.”) Teleportation shares the time travel “conservation” problem, stated succinctly by a commentator last week: “My issue with time travel either way is the conservation of matter and energy; can’t be created or destroyed. If you travel forward or backward in time, where did all those additional atoms come from? If you look at yourself in the future, or past, where did the energy and atoms come from to create two (or more) of ‘you’?”

*That is, as it’s generally meant. You can, of course, get into the future à la Rip Van Winkle (who slept for 20 years) or Woody Allen in Sleeper (cryogenics); or by zipping into space and returning to find you’ve aged less than your twin thanks to your worldline having veered off from the stay-at-home twin’s inertial frame. None of which is really time travel. Neither is awakening in hospital after an operation—having lost three hours of your life and not knowing if you’re still the ‘you’ that was anesthetized earlier. (For real time travel, you need a DeLorean. Or a British blue police box: the best time travel yarn, IMHO, is the Doctor Who episode “Blink,” which features very little of the Doctor but much of the awesome be-still-my-heart Carrie Mulligan.)

Back to teleportation. As I (and Wikipedia) understand it, the Enterprise’s Transporter converts a person into an “energy pattern” which is then beamed at the speed of light to, say, the surface of a nearby planet where they’re reconverted back into matter. This means, to put it bluntly, that the Transporter is actually a killing machine. The ‘you’ that materializes on the planet may look and sound like you, may even feel like you. You remember how you felt when you weren’t picked for your class play, what it was like when you nearly drowned. But it isn’t really you. The atoms that constituted ‘you’ are still back on the Enterprise—or perhaps they’ve been ejected into space along with the garbage. Somehow the Transporter beam was able to muster up enough atoms/quarks on the planet to re-make you down there. On your return to the ship, there has to be a couple of hundred pounds of spare stuff hanging around, ready to be converted back into another fake you.

Or

two ‘you’s.’ That was the plot of “The Enemy Within,” when

good-Kirk and bad-Kirk returned, thanks to a Transporter accident.

This plot eliminated the possibility that the Transporter actually

beamed particles (as opposed to massless information) to and

fro—meaning that it really does kill off the transportee. The

resulting person is an exact digital copy of the “actual” person

made from fresh material. Suppose it didn’t—suppose the

Transporter “merely” scanned the person, letting them live, while

their clone was created somewhere else. Clone returns, insists he or

she is the real crewmember (since it must feel that way to them)

while the stay-on-the-ship crewmember says the same thing. In fact,

it might be a good idea to keep the original on the ship in case the

clone meets a fatal accident down there. While we’re at it, why

return the clone to the ship anyway? Have them report back and then

maroon them on the planet, adios amigo.

If you’re a trekkie, you’ll be way ahead of me. That was the plot, more or less, of TNG’s “Second Chances.” Riker both stays on the planet and returns to the ship (disruption field, you know). Neither Riker knows about the other—until eight years later, when the Enterprise arrives, the two meet…and a soap opera ensues, with Counselor Troi as the romantic interest.

Don’t worry, none of this is gonna happen. “Physics students at University of Leicester calculated that to ‘beam up’ just the genetic information of a single human cell, not the positions of the atoms, just the gene sequences, together with a ‘brain state’ would take 4,850 trillion years assuming a 30 gigahertz microwave bandwidth.”

I’m with McCoy on this. Use the damn shuttle.

CLICK TO MANAGE