In our families, the end of July and beginning of August is birthday season, meaning that I find myself writing emails and Facebook messages “hoping this coming year will be wonderful for you,” perhaps alluding to the past COVID-laden year (as if it were over!), recognizing it’s been tough for all of us.

Am I being unkind, sending “hope” messages? Hesiod, the ancient Greek farmer-poet (born around 750 BC), thought so. He was the first to record the old tale of Pandora’s jar (not a box—the word was pithos, or urn) that contained a passel of evils and “countless plagues” including sickness and death. (Curiously, Pandora means “having all gifts.”) They had been put in there by Zeus, king of the gods, as revenge on mankind for Prometheus’ theft of fire from heaven. Zeus gave the evil-laden jar to Epithemeus, whose sister, Pandora, couldn’t contain her curiosity…and opened the jar when it was left in her care. (Helen, Eve, Pandora…always a woman screwing things up???)

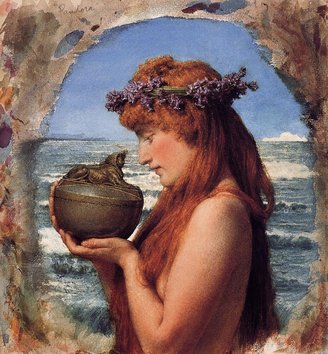

Should she or shouldn’t she? Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s (1836–1912) watercolor of an ambivalent Pandora. (Public domain)

One “evil” remained after the others were released: Hope (elpis), who had hidden under the rim of the jar, thus leading to nearly three thousand years of philosophical speculation about the meaning of the story. Was the jar a prison or a pantry? Was Hope, always personified as female, trapped inside so humans could be kept safe from her? Or was she kept close to home, in the pantry as it were, to torment us forever?

Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche thought the latter: “…now man has the lucky jar in his house forever and thinks the world of the treasure. It is at his service; he reaches for it when he fancies it [taking] the remaining evil for the greatest worldly good—it is hope.” (Nietzsche pauses to light another cigarette; he was a chain smoker.) “For Zeus did not want man to throw his life away, no matter how much the other evils might torment him, but rather to go on letting himself be tormented anew. To that end, he gives man hope. In truth, it is the most evil of evils because it prolongs man’s torment.”

That was 100 years ago. Here’s a more up-to-date take on the story, from Swiss-British author Alain de Botton: “…we are usually cast into gloom not so much by negativity as by hope. It is hope—with regard to our careers, our love lives, our children, our politicians and our planet—that that is primarily to blame for angering and embittering us.” For anyone in this country who might have missed his take-no-prisoners approach, he goes on: “…secular Americans, perhaps the most anxious and disappointed people on earth, for their nation infuses them with the most extreme hopes about what they may be able to achieve in their working lives and relationships.”

So much for me “hoping” my relatives will enjoy the fruits of all their hard work up until now, with “the best year ever” (how often have I written that phrase?), starting with this year’s birthday? Would it be more honest to write them, “If I tell you this is going to be a great year, I’m sowing the seeds of disappointment. Sometimes it will be great, other times it’ll suck. Such is life. Get over it.”?

Nope, can’t do that. I live in hope, my genes love hope. We are born into the world with hope firmly ensconced in our brains and bodies. I plan hoping for the best, not the worst. Our ancestors hoped they would come back to camp with a dead something—protein!—on their shoulders. I hope I’ll be able to travel freely again; I don’t hope for a full return to masks and lock-down.

Like many wise sayings, this one, attributed to the mythical Buddha (who said so many wise things, Facebook can barely keep up), works for me: Make plans, but hold them lightly.

CLICK TO MANAGE