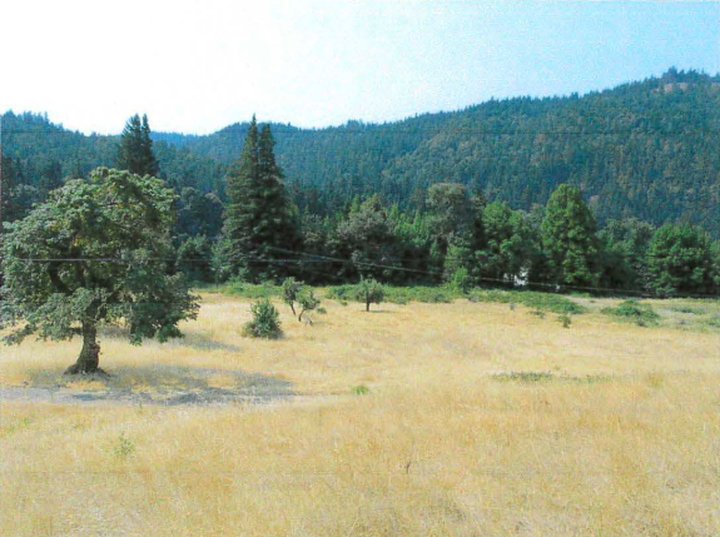

The Rolling Meadow Ranch near McCann encompasses 7,110 acres, some of which run along the bank of the Eel River. | Photo from an Initial Study via the County of Humboldt.

###

Over the course of his long career, Florida resident Andrew Machata has been involved in many industries. A mechanical contractor by trade, he has owned and operated a heating and plumbing company, a construction firm, a mining corporation, a charter jet company and a yacht company. He ran a sod farm for a while.

He also has bought and sold investment properties in numerous states, including an “absolutely gorgeous” expanse of lakes and wildlife, the 5,830-acre Rolling Meadow Ranch, which he sold in 2002 to the State of Florida and the South Florida Water Management District for $38 million. That name, “Rolling Meadow,” has been affixed to several of his properties and companies over the years.

Now, at age 83, Machata is getting involved in the marijuana industry, though in a recent phone conversation with the Outpost he said he’s had second thoughts.

“If I’d have known what I was getting into I probably wouldn’t have done it,” he said. “It’s been such an ordeal.”

Machata owns a sprawling 7,110-acre ranch on the banks of the Eel River near the remote community of McCann. After selling Rolling Meadow Ranch in Florida, he went flying around the country in search of another investment property as a means of deferring capital gains taxes from the multi-million-dollar sale. He considered a place in Colorado but didn’t pull the trigger.

“When I came to Humboldt County, the piece there was a real lush spot with forests, a lot of water on it, creeks … . That’s what I bought it for, all the natural beauty,” he said. And though it looks nothing like his Florida ranch, which was was home to wild pigs, panthers and deer, he christened it with the same name: Rolling Meadow Ranch.

Sixteen years later, Machata is hoping to finally turn a profit off the property. In 2016 he nearly sold it for $15 million to The Wildlands Conservancy, a nonprofit that specializes in converting undeveloped properties into nature preserves, but the deal fell apart after a higher bid came in, only to fall through. So instead, Machata applied for six conditional use permits to develop an 8.5-acre commercial cannabis operation — despite a lack of expertise.

“I know nothing about marijuana,” he said. In fact, he doesn’t even really approve of the industry. “I don’t believe in the recreational,” he continued. “I believe in the medical.” Recreational marijuana has a negative influence on some kids, he explained. “These [proposed] facilities are set up to grow to a quality, medical-grade marijuana. I think even if they legalized it everywhere there’s gonna be need for that.”

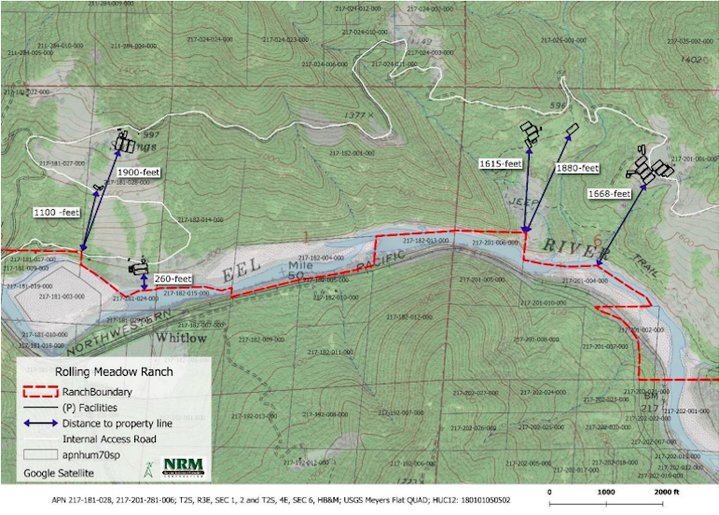

Regardless of the eventual quality, Machata’s proposal, which was approved by the Planning Commission on January 21, calls for a commercial operation with up to 16 greenhouses in four distinct cultivation areas, plus propagation and processing facilities, a 20-space parking lot, plus a septic tank and a leach field.

The operation would employ up to 30 people, including 22 full-timers, for year-round cultivation. The estimated annual water supply of 4.6 million gallons would be supplied by three groundwater wells, plus rainwater catchment into a 320,000-gallon hard-sided tank. PG&E would be enlisted to supply power to the site.

In approving the proposal, the Humboldt County Planning Commission found that a full environmental impact report isn’t necessary. Instead it accepted a less-stringent environmental review document called a mitigated negative declaration, or MND.

Chair Alan Bongio said he’d recently visited the property and was struck by how much water is there. He commended Machata for keeping the land intact as one big ranch, rather than subdividing it and selling it off. And he said this proposal will be less impactful than many alternatives.

“What else could you do there?” he asked. Logging it would be “way more destructive.” Growing any other crop would be equally disturbing to the land. “It seems like [this project] is a pretty small impact on a very large piece of property,” Bongio concluded.

Fellow Planning Commissioner Melanie McCavour agreed, saying no “substantial evidence” had been provided to show that the MND prepared by county staff was insufficient.

However, many Humboldt County residents feel quite strongly to the contrary. They argue that such a wild and remote environment is an inappropriate spot for an industrial weed farm. (The land is currently accessed via Dyerville Loop Road and the low-lying, single-lane McCann Bridge, which is often closed due to flooding from November through April, though Machata plans to build new access roads.)

A petition in opposition to the project has gained more than 1,700 signatures. Environmental groups have voiced concerns about the project’s potential impacts to groundwater, wildlife habitat, fire risk and more.

Three county residents have appealed the Planning Commission’s decision to the Board of Supervisors, which will consider the matter at its regular meeting on March 9.

With the recent approval of this and other cannabis cultivation projects in pristine, remote locales, some local residents and regulatory officials are questioning whether these kinds of grow operations are really what county officials had in mind when they crafted cannabis land use regulations. Wasn’t the intention to get weed grows out of the hills and into plain sight?

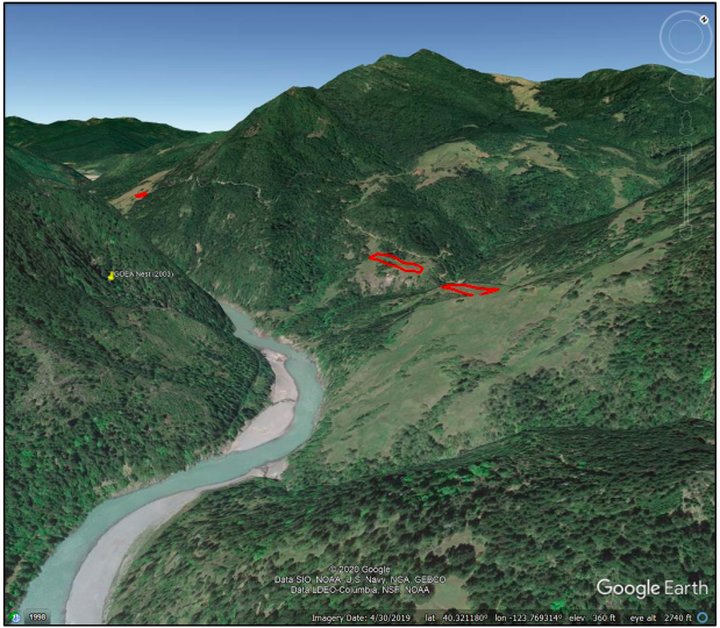

A documented golden eagle nest site (yellow pin) is within line-of-site of proposed cultivations areas for Rolling Meadow Ranch (shown in red). | Image created by CDFW as part of a comment letter submitted to the county.

###

Environmental scientists with the California Department of Fish & Wildlife have recently raised such concerns with the county. At a September meeting of the Planning Commission, for example, CDFW Senior Environmental Scientist Specialist Mike van Hattem brought up what he called “the elephant in the room” — namely, “the approval of large, industrial cultivation sites on remote wildlands.”

The commission was considering another controversial weed grow: two-acres of mixed-light cultivation in eastern Humboldt, near Maple Creek, from a company called Adesa Organics LLC. CDFW scientists had some specific concerns about the project — not least of all its potential impacts to golden eagles, a fully protected species in California — but van Hattem also wanted to address the larger trend.

The county’s Commercial Medical Marijuana Land Use Ordinance, adopted in 2016, says new outdoor and mixed-light grows are only permitted on parcels with prime agricultural soils on slopes of 15 percent or less. Van Hattem and other CDFW officials reviewed the zoning at the time and saw that most parcels with prime ag were located on flat expanses of existing farmland, such as the Eel River Valley and Arcata Bottoms.

The Adesa project, like Rolling Meadow Ranch, is in the middle of nowhere, accessible only via narrow county roads beyond most services and civilization. Van Hattem posed a question to the Planning Commission: “Is this what you thought was intended? Do you want large industrial cultivation sites in remote wildlands of your county?”

In this case, evidently so, because the Planning Commission approved the project, and on appeal the Board of Supervisors upheld the decision. But critics have become increasingly vocal about what some call “the prime ag loophole”: Property owners can hire soil scientists or geologists to come out and inspect their land, and if portions of their property have soil that meets the criteria of the California Department of Conservation, it can be designated “prime ag,” potentially making it eligible for a cannabis operation in Humboldt County, no matter how far-flung the land may be.

CDFW raised objections again with the Rolling Meadow Ranch project. In a 15-page comment letter submitted to the county on Dec. 30, environmental scientist Greg O’Connell argued, “An unintended consequence of requiring new cultivation on prime agricultural soils (and allowing new areas to be classified as such with no minimum size) is the targeting of small, isolated, flat grasslands within larger prairie complexes on steeper slopes.”

That describes Machata’s property quite well: scattered grassy plateaus nestled within hundreds of acres of forested hillsides. “These habitats [the flat grasslands] are vital elements of biodiversity and provide important habitat for wildlife,” O’Connell wrote.

The county’s Planning and Building Department has received more than 150 applications for commercial cannabis cultivation projects within two miles of documented golden eagle nest sites. O’Connell said the cumulative impacts of these projects “could eliminate golden eagle territories within Humboldt County” while harming a long list of other special status species that depend on grassland habitats.

In a phone interview Monday, van Hattem said that while the county required Machata to make some much-appreciated alterations to his plan in response to CDFW feedback, and while the project’s wildlife surveys were adequate, “The bottom line is that this project will transform a very wild area.”

Putting a lot of people into environments where there used to be none changes the way wildlife uses the habitat, he said. And he reiterated that these kinds of projects are simply not what he and his colleagues were envisioning during the drafting of the county’s first cannabis land use ordinance.

“I don’t think any of us thought this was what we were getting out of the ordinance,” van Hattem said. Sun Valley Floral’s recently revealed proposal for 23 acres of greenhouse cultivation in the Arcata Bottoms is large, sure, he said, but it’s on land that’s been in use for generations, near population centers with adequate traffic access.

He made a point of noting that his agency isn’t against legal weed. “It’s not about cannabis; it’s about proper land management,” he said. “Bringing everybody into the legal light, that’s a good thing. It’s why we do planning efforts — to do the best things we can for the county, our watersheds and rivers.”

He just doesn’t think projects like Rolling Meadow Ranch fit that bill. “It’s troubling to put these big projects way out there,” he said.

Topographical map showing the distance of Rolling Meadow Ranch project facilities (those tiny black outlines) from parcel boundaries along the Eel River. The squiggly white line represents a proposed internal access road. | Image via County of Humboldt.

###

The notice of appeal of the Rolling Meadow Ranch project was filed last month on behalf of Fran Greenleaf, John Richards and Patty Richards, all of whom live in close proximity to the property. It argues that the Planning Commission erred in concluding that there’s no substantial evidence that the project may have significant environmental impacts and requests that the Board of Supervisors either require a full environmental impact report or deny the application altogether.

The appeal letter describes the setting as “remote” and “undeveloped” and says the project would “forever change the character of the area and pose a danger to public welfare.”

The appeal’s list of concerns include intensified land use, increased traffic and noise, year-round groundwater extraction, the expansion of utility infrastructure, safety and security concerns and “heightened fire danger in a high-fire-risk area located far from public safety resources .”

Reached by phone recently, appellant John Richards said that last one is his main worry.

“You put that many people into the wildlands and it just ups the odds,” he said. “And response time out there is gonna be really slow.”

The conditions of Dyerville Loop Road and McCann Road only add to the problem he said, describing certain sections as little more than “a ledge carved into a cliff.”

It just fundamentally seems like an inappropriate spot for an operation of this size. “Why put that there?” he said. “It should be in Watsonville or the Central Valley.”

Fellow neighbor Mary Gaterud agrees. She has spoken against the project publicly and launched the online petition opposing it. She believes a certified hydrogeologist needs to be consulted to ensure that the wells on Machata’s property are not connected to the nearby Eel River, among other concerns.

“Siting these large grows in remote, mountainous terrain — that was not intended by the county ordinances or the county general plan,” Gaterud said. It’s not sensible planning to site an operation like this out away from services and the highway.”

At the January 12 Planning Commission hearing, however, commissioners and staff alike argued that the rules, as currently written, justify approval of Rolling Meadow Ranch.

Pressed by Commissioner Noah Levy about why staff didn’t require an EIR, Planning and Building Director John Ford said he and his staff are “factually driven,” and the facts simply didn’t elevate the project’s anticipated impacts to that level of review.

The 259-page initial study and environmental checklist, conducted by Eureka-based Natural Resources Management Corporation, analyzed the environmental impacts. Regarding the water source, it quotes David Fisch of Fisch Drilling saying the three wells he dug in June of 2019 are in perched bedrock “with no hydraulic connection to any surface water.”

“Now,” Ford said at the meeting, “may water ultimately flow through fractured rock and at some point connect with the Eel River or a nearby creek? I don’t think even a hydrogeologist could give you an absolute answer on that.” But that’s not the standard, he said. “The test is: Is this a diversionary water source? We believe it’s not.”

As for the golden eagle, Ford said surveys and supplemental information demonstrate that the previously documented nest site is simply not there anymore. O’Connell, with CDFW, countered that golden eagle pairs may return to prior nesting sites after many years or even a decade, but an attorney for the project said such theoretical conjecture “doesn’t rise to the level of substantial evidence of a significant impact” that would justify an EIR.

Reached by phone on Tuesday, Ford acknowledged that previously unidentified prime ag soils have been designated as such in a lot of remote settings, but he disputed the characterization of this practice as a “loophole.”

“It’s really a technical issue,” he said. “I don’t think it’s a loophole; I think it’s very clear.” The goal of the prime ag requirements was to get grow operations off of steep hillsides that required grading and onto flatter, more suitable land for growing. “It’s just that we’re finding prime ag soils where they hadn’t been previously identified,” he said.

But do projects like Adesa and Rolling Meadow Ranch run counter to the county’s vision for legal commercial cannabis? Ford said such questions are judgement calls placed in the hands of the Planning Commission and the Board of Supervisors.

Machata, for his part, had no idea that his foray into the marijuana industry would require so many surveys, studies, revisions and concessions. Speaking on the phone from Florida he said, “Sometimes I get myself in more things than I want to. I think this is one of ‘em.”

But he defended his stewardship of the land and cited examples of measures he’s taken to protect the environment. He agreed to set aside 1,600 acres of his property as a contiguous piece of untouched land. He agreed to use “first class” greenhouses with no water runoff or nighttime light pollution. He agreed to employ electric buses on the property to carry employees around. And he hired consultants to write a report that “covers everything from frogs to big-eared bats.”

Since he knows nothing about cannabis himself he said he’ll probably enlist local growers to run the facility.

“My intentions are good,” Machata said. And he offered his own conclusion about the project’s impacts: “Everything we’re doing really does not affect the environment.”

More than a few local residents, nonprofit leaders and environmental scientists have argued otherwise. Next Tuesday, the fate of Rolling Meadow Ranch will be a judgment call in the hands of the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors.

The cumulative impacts from such individual judgment calls will not be clear for years or perhaps decades to come.

CLICK TO MANAGE