An 8,000-square-foot home being built by local business owner Travis Schneider has been halted mid-construction for various permit violations. | Photo by Andrew Goff.

###

Planning Commission Chair Alan Bongio spent much of last week’s meeting expressing frustration and outrage.

“It just doesn’t make any sense to me,” he said at one point about halfway through the three-hour meeting. “I mean, this is the craziest thing I’ve watched. I would say this is the most egregious thing that I have seen in 11 years on the planning commission … .”

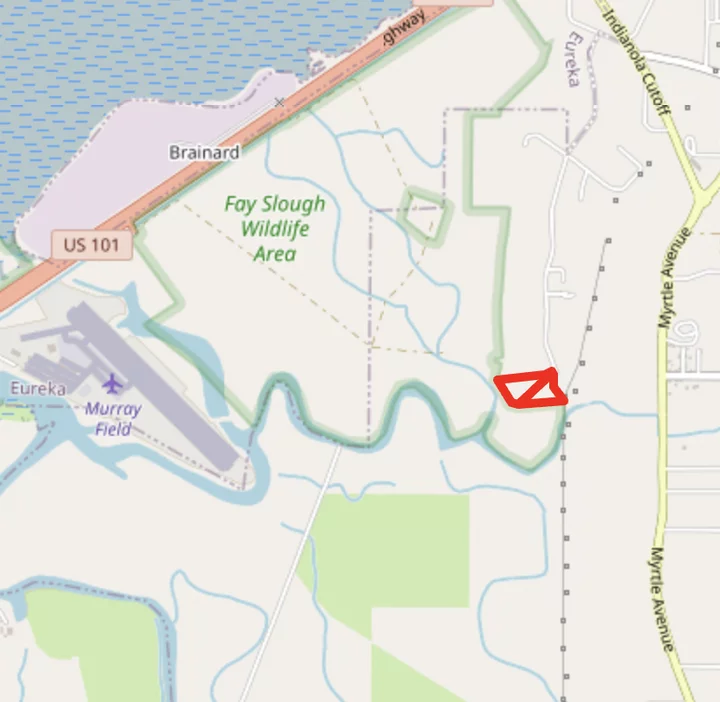

The matter under discussion concerned permits for a very large, partially built home off Walker Point Road, a one-lane strip of asphalt accessed via the Indianola cutoff between Arcata and Eureka. The dead-end road traces the ridge of a knoll that overlooks the surrounding estuarine wetlands including Fay Slough, Freshwater Creek and, across the freeway, the shifting colors of Arcata Bay.

Historically the Walker Point area was known as Da’dedi’lhl, which means “sunshine” in Soulatluk, the language of the Wiyot people.

Late last year, after starting construction on his very large home, the applicant, local business owner Travis Schneider, violated the terms of his Coastal Development Permit. He did so by laying down an un-permitted access road through some environmentally sensitive habitat and by using a CAT 310 excavator to clear blackberry brambles and other foliage from the property, potentially damaging tribal cultural resources in the process.

The county issued a stop work order on December 27, and three Wiyot-area tribes — the Blue Lake Rancheria, the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria and the Wiyot Tribe — were called in for consultation. [DISCLOSURE: The Blue Lake Rancheria is a minority owner in the Outpost’s parent company, Lost Coast Communications, Inc.]

At their direction, an archeologist was hired to assess the damage. The California Coastal Commission got involved, and construction of the home has remained at a standstill for the past eight months.

Schematic image showing the Schneider home’s original footprint along with borders of the wetland setback area. | Image via County of Humboldt.

###

During that time, several meetings between the various parties have been held, tribal historic preservation officers have been consulted and ideas for rectifying the situation have been advanced, argued over and revised.

Bongio’s frustration, which was shared to at least some extent by some fellow commissioners and county staff, stemmed from his belief that there had finally been a breakthrough. A meeting with the concerned parties had been held on Aug. 2, and many who attended left with the impression that an agreement had been reached.

The Planning Commission meeting was scheduled for this past Thursday, with staff recommending a series of mitigation measures that had been proposed by the Wiyot and Blue Lake tribes and agreed to by Schneider.

However, just minutes before the deadline to submit public comment for the meeting, both the Blue Lake Rancheria and the Wiyot Tribe sent letters saying they still had concerns. They called for additional corrective actions and more time to review matters and iron out the details.

The Coastal Commission’s North Coast enforcement officer also submitted a letter saying the agency remains concerned about the “very significant” permit violations. The agency pointed out that it has the authority to take over enforcement of the Coastal Act and Local Coastal Plan.

Bongio was livid. He accused the tribes of reneging on their agreement, adding, “I have a different term for it but, you know, whatever.” He said it was the most egregious behavior he’s seen not just in his own time on the Planning Commission but in more than three decades he’s been watching county government, and he warned that it will set a new precedent.

“Nothing will happen in Humboldt County because everybody is going to be afraid,” he said. The pitch of his voice rose with his emotions. “Pretty soon, the next thing you’ll have to do is you’ll have to go before — and you already do — have to go before the Indians. But … it’s just gonna be a whole new thing that everybody has to go through every time there’s a project. You name it, whatever it is, you’ll have to go before them. And the Coastal Commission. This is — this has went way too far. This should have been stopped a long time ago.”

The meeting ended in a stalemate. Planning Commission member Melanie McCavour had recused herself because she’s employed as the tribal historic preservation officer for the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria, and participated in the meeting only in that capacity.

The remaining six commissioners deadlocked three-to-three on a vote to approve permit modifications that could have allowed Schneider to resume building his house (though the dissenting commissioners pointed out that the Coastal Commission might overrule such a move). The commission wound up voting to continue the matter to its September 15 hearing. [CORRECTION: The hearing was continued to September 1.]

But the heated tenor and charged language in last week’s meeting could make a resolution on the issues even more elusive.

Schneider was not in attendance, but in a letter read into the record by his representative he admitted making mistakes and said the resolution process has been expensive, exhausting and time-consuming.

“The emotional psychological toll that this has taken on my family is immeasurable,” his letter said. Schneider has lost faith in the negotiations. His letter concluded by saying that the “moving target” for resolution “leads me to believe that there are parties that sincerely don’t want to resolve this matter.”

On the other side of the table, tribal representatives have now been accused of lying and manipulating the process, and those accusations caused significant offense. In emailed responses to questions about the meeting, Wiyot Tribal Administrator Michelle Vassel described the proceedings as “a shocking abuse of power and display of discrimination.”

Map showing the location of the two Schneider-owned parcels where he intends to build his family home.

###

It was four years ago — August 22, 2017 — when the county approved an administrative Coastal Development Permit for construction of the Schneider family home. The approved project consisted of a single-family residence measuring roughly 8,000 square feet with an attached 1,000-square foot cellar, a four-car garage and two-car parking area.

In his staff report last week, Senior Planner Cliff Johnson acknowledged that this is “larger than typical for single-family residence” but said that so are many of the other houses in the Walker Point area, so the plans were deemed consistent with the character of the surrounding neighborhood.

Schneider owns Pacific Affiliates, a Eureka-based civil engineering firm with licensed contractors spread across the western United States plus Guam and British Columbia. The company owns and operates a dock and warehouse on Humboldt Bay, and for nearly three decades the Harbor District has contracted with Pacific Affiliates for permitting, design and management of dredging operations, according to the company website. Schneider is also a local developer with commercial properties, RV parks and apartment buildings.

Schneider’s 3.5-acre parcel includes areas that have been designated an archaeological site and tribal cultural resource. Per the terms of his permit, all construction was to take place at least 100 feet away from any wetland habitat in order to protect the archeological and biological resources. No trees were proposed to be removed, and specific conditions of approval included the requirement to retain the native blackberries, refrain from removing any vegetation within the 100-foot wetland setback and keep all construction activity above the property’s 40-foot contour line.

This past December, county planning and building staff were informed that grading and ground disturbance had occurred within the prohibited area, possibly damaging both the biological resources and the tribal cultural resource. Because of these violations, the county posted a stop-work order on the property on December 27. However, construction activity continued for several weeks after the stop-work order was posted onsite.

Eventually, the county hired William Rich and Associates to conduct an archaeological damage assessment and ordered Schneider to hire a biologist to assess the damage done to biological resources on the property. Investigations and surveys revealed three big permit violations.

Screenshot from a PowerPoint presentation showing the un-permitted access road built on the Schneider property.

###

First was the temporary access road, which had been cut into the prohibited area below the 40-foot contour and within the 100-foot setback.

Second, Schneider had used a CAT 310 excavator, outfitted with a hydraulic mulcher head, to conduct “major vegetation removal” within both a designated Environmentally Sensitive Habitat Area (ESHA) and a known tribal cultural resource. In addition to removing more than an acre of blackberry bushes, Schneider had taken down a 16-inch willow tree and four alder trees ranging in size from three to 14 inches.

Third, the house was being built “in a location not in accordance with the approved site plans,” according to a staff report. Surveys revealed that the home’s footprint is now within 100 feet of the designated wetland, which means it’s in violation of the county’s local coastal plan and automatically makes the project appealable to the Coastal Commission.

A “significant number of artifacts” were found during the limited survey effort, and the archeologist determined that the site is eligible for listing to the California Register of Historic Resources because it could “address a range of scientific research questions,” a staff report says.

The archeologist also concluded that the disturbance caused by the heavy equipment and vegetation removal did not affect the integrity of the site’s scientific value and that, “No evidence of cultural material destruction or damage was uncovered.”

But the Wiyot Tribe and the Blue Lake Rancheria say the disturbance to the tribal archeological site has been “culturally significant” and they’ve asked for more thorough investigations, including an excavation, and stronger protection measures to prevent further damage to the site.

On June 10, representatives from the Wiyot Tribe and the Blue Lake Rancheria met with county and coastal commission staff to discuss potential resolutions to these matter. Following the meeting, Blue Lake asked for a couple of extensions, but on July 26 the county received a letter with joint comments from the Wiyot and Blue Lake tribes recommending new conditions of approval.

Another meeting was held (virtually) on August 2. County staff members attended along with Coastal Commission staff and representatives of Schneider and all three of the Wiyot area tribes. Exactly what was agreed to at that meeting, and by whom, has become a major source of contention. Schneider’s representatives and county staff left believing that a consensus had been reached, with Schneider agreeing to meet 11 resolution points that the tribes had proposed.

However, just before last Wednesday’s noon deadline to submit comments for the following day’s Planning Commission hearing, both the Wiyot Tribe and the Blue Lake Rancheria submitted in letters with additional comments.

Blue Lake’s letter, signed by Tribal Administrator Jason Ramos, said “it remains unclear” how the proposed conditions would be implemented, monitored and, if necessary, enforced. The letter also called on the county to revoke Schneider’s Alternate Owner Builder permit, which allows for more lenient terms than a standard permit, and said more time is needed to fully analyze and address the permit violations.

The Wiyot Tribe’s letter, signed by Vassel, objected to county staff’s recommendation to approve Schneider’s permit modifications, which would allow him to resume building his family home. It said the conditions of approval were “legally and structurally deficient” and action on the permits should be deferred.

Both tribes have called for archeological excavations on the property, but the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria objects to that particular request. McCavour explained in her testimony as tribal historic preservation officer, “We, like most tribes, feel excavation of resources is considered disrespectful and therefore not a mitigation, especially with shell midden.”

The Bear River Band, meanwhile, submitted its own letter to the Planning Commission on Thursday, after the public comment deadline had passed. Nevertheless, the letter was passed along to the commission for consideration. In it, the Bear River tribe said it was still onboard with the 11 mitigation measures discussed on August 2, but in lieu of excavation it proposed a new condition requiring Schneider to place $38,000 into an account designated by the three tribes to be used for mitigation of cultural resource impacts.

Schneider agreed to that provision ahead of the meeting.

The partially constructed roofline of Schneider’s home can be seen above the foliage beyond a wetland slough. | Photo by Andrew Goff.

###

At Thursday’s meeting, a neighbor of the Schneiders’ Walker Point property, Sharon Cockcroft, stood at the lectern and accused Schneider’s construction crew of blocking access to a trail along her deeded easement. She said the crew dropped “a full dumpster” of waste on the trail, including construction materials, household garbage, a used oil filter, oily rags, fenceposts and more.

“Travis Schneider has demonstrated over and over that he will do as he pleases,” she said.

Attorney Brad Johnson appeared on behalf of Schneider, who was on a long-planned family vacation to New York. Johnson brought up the 11 resolution points discussed at the August 2 meeting, noting that Schneider had agreed to accept all of them.

“I expressly sought confirmation from each of the stakeholders that these 11 points represented a resolution to this matter,” Johnson said, and he believed he had gotten that confirmation from each of the tribes (with the notable exception of the excavation matter) — only to find out otherwise via the letters that had arrived the previous day.

Johnson spoke about the principle of “proportionality,” saying the remediation measures should be roughly equivalent to the scope of the violations, which was no longer the case here. He said the tribes had made a concerning change of position between August 2 and that day’s meeting.

“It calls into question the ability to, I think, trust and work with important community stakeholders,” he said, adding that “truth and fair dealing are cornerstones” to such negotiations. “The new demands that we’re seeing, they’re not fair,” he said. “They’re not equitable, they’re just not fair, they just aren’t proportional to the three violations at issue.”

Bongio weighed in, saying, “It’s puzzling to me that we got three letters in a row at 11:50-something. The cutoff is 12 o’clock.” (He was referring to the letters from Blue Lake, the Wiyot Tribe and the Coastal Commission, which you can download and read in their entirety by clicking here.)

“They made this agreement and then all of a sudden, at the 11th hour, these three letters show up. I mean, it can’t be coincidence,” Bongio said. “I’m sorry. I’m just going to say it the way it is.”

McCavour said Bear River was also unaware of the proposed new mitigation measures until those letters came in the day prior.

Local real estate agent Tina Christensen appeared on behalf of Schneider.

“He made a mistake, and he admits it,” she said. “So do we send him to jail? Or do we try to resolve it?”

She said she was present at the August 2 meeting. “We left that meeting thinking that we had all worked together to bring a closure to this issue. That is not what happened. And I am sorry, but they lied,” she said, referring to the tribe’s representatives.

She proceeded to read a letter from Schneider into the record. In it, Schneider recounted a bit of his personal history, saying he was born and raised just over two miles from the construction site and that he and his family are “anchored to Humboldt County.”

Schneider admitted to violating the stop-work order while he “sought clarity” from the county.

“I’m not innocent in this matter,” his letter said, per Christensen’s reading. “I did install a temporary rock road to access the southwest corner of our home for the purpose of installing windows and siding. I did mow berry vines. I did not know blackberry vines couldn’t be mowed in the coastal zone. I’m sure that 90 percent of the people in this room have mowed blackberry vines. … I thought what I was doing was acceptable.”

After finishing the letter, Christensen again accused the tribes of lying.

Planning Commissioner Peggy O’Neill addressed that accusation, saying, “I’m really offended that you would call people liars.” A longtime employee of the Yurok Tribe, O’Neill said she knows from experience that tribal employees may agree to things in a meeting, but they have to take all decisions back to their tribal councils, who maintain the ultimate authority.

“So to call them liars or, you know, deceivers or whatever is really unfair because they’re employees and consultants,” O’Neill said. “And they’re going to do the best job they can but they don’t speak for the elected officials.”

Bongio pushed back, defending the use of the word “liar” in this scenario.

“I don’t like using that word, either, but sometimes a word fits, and there may be some places in this [situation] that that word does fit,” he said. “How much time is enough time? This gentleman and his family have had their project red tagged for eight months. How much time do the tribes need?”

He grew increasingly animated as he spoke. “This is very troubling to me.,” he said. “These are our trust agencies, and they went after one individual. I’ve lost all trust in the tribes in what I’ve watched. It’s going to take a lot to rebuild that for me.”

Fellow Commissioner Noah Levy had wondered aloud earlier in the meeting why no representatives from the Wiyot and Blue Lake tribes were in attendance, and Bongio asked the same question. “There’s not one in this audience,” he said. He then suggested that the three Wiyot area tribes should figure out what they want.

“Let that be between the Indians,” he said. Here’s the clip:

Following Bongio’s comments, Levy said he was “troubled and disappointed.”

“You said a lot there, Alan, and I can’t agree with all of it, I gotta say.” But Levy went on to say he shares Bongio’s bewilderment at not getting to hear from anyone with the Wiyot or Blue Lake tribes. “Just like any other respected trust agency, when they throw us a curveball I think they owe it to us to try to communicate and explain the confused signals that we’re getting from hearing one thing and then another thing.”

Humboldt County Planning and Building Director John Ford said county staff did not recommend putting the matter off for even a couple more weeks, despite the specter of being overruled by the Coastal Commission.

“What we tried to show [in the staff presentation] is that this has been a process that has gone on for seven, eight months of really trying to address the concerns of [the] tribes,” Ford said.

He was in attendance at the August 2 meeting and, like others, believed that a full resolution had been reached.

”I think that we’ve been very methodical in trying to understand what the damage is and what the remedial actions should be. I think there is a good proposal there. That proposal actually was written in a letter by the tribes. … And it’s agreed to by the applicant, and it’s written into the conditions of approval to implement just exactly that. I don’t know what else there is to do.”

Planning Commissioner Thomas Mulder, who attended the meeting via phone video chat, agreed with Bongio that acquiescing to the Wiyot and Blue Lake tribes’ last-minute demands could set a bad precedent. He added, “This is an open construction project that looks to be needing some winterization.”

Fellow commissioner Mike Newman said he was in favor of approving the permit modifications and allowing Schneider’s project to move forward.

But Levy again cautioned his colleagues against shining on the Coastal Commission.

“Wouldn’t it be a waste of our time to go ahead and approve [the permits] when they’re asking for a continuance in the same letter that they’re reminding us that they have the authority to overrule us?” Levy asked. He said it would be cleaner to continue the matter to a date uncertain.

“I think there’s room to imagine that there could be a good faith disagreement about whether all of the aspects of the meeting, the verbal meeting on August 2, are properly encapsulated in the conditions of approval,” he said.

But Mulder persisted, making a motion to approve the permit revisions and saying he believed the county has done its due diligence. Newman seconded the motion, but Commissioner Brian Mitchell sided with Levy.

“I’m having a hard time getting on board with some of the language and comments that are being made towards our partners and trustees … ,” he said. “And I have witnessed firsthand the folly of thinking that you can ignore a Coastal Commission letter and just try and go do what you think is best. I’ve never seen it work out.”

Bongio, Mulder and Newman voted to approve the permit modifications; Levy, Mitchell and O’Neill cast “no” votes, so the motion failed.

Bongio remained upset.

“Since the beginning of this thing, every time [the tribes] asked for something, then they came back [and asked for] something else, and then they asked for something else, then they asked for something else and, like, the poor guy’s been just getting nickeled and dimed over and over and over,” he said.

“The tribes are gonna do whatever they wanna do anyhow. … I can tell you, another week isn’t going to make it or you know, three weeks, whatever it is, is not making any difference. They’re going to do what they’re going to do. That’s what these entities do. … If you can’t take these trust agencies at their word what are we going to do?”

Bongio mocked the concerns over vegetation removal, saying, “So now we have the briar police? Because I didn’t know you couldn’t cut briars. … I’m not saying that was right. But if that’s the case, are the briar police gonna go after everybody?”

He then theorized that the whole controversy could maybe have been stirred up by that neighbor who’d spoken early in the meeting about infringement on her trail easement. Without offering any evidence he speculated that she’d reported her complaints to the tribal historic preservation officer (THPO) in Blue Lake and that things snowballed from there. The neighbor, who was still in the audience, tried to deny the accusations.

Another clip:

After a bit more discussion, Newman saw the writing on the wall. No resolution would happen this day. He made a motion to continue the matter to a future date. Five of the six participating planning commissioners agreed to do so. Bongio was the lone dissenter.

Reached for comment after the meeting, Wiyot Tribal Administrator Michelle Vassel expressed disappointment and anger at some of the accusations and language used in the meeting. She said the tribe had submitted its written comments before the deadline, fully in accordance with meeting rules.

“There is no requirement to attend in person if you wish to make comments,” she said in an email. But regardless, she said, she actually was in attendance, albeit remotely. She had logged in via Zoom and even tried to participate.

“I was signed in as Michelle Vassel, Tribal Administrator, Wiyot tribe,” she wrote. “I am the person whose comments were submitted in writing to the Commission by the deadline and [I] was in attendance for the entire meeting. I attempted to gain the Chair’s attention by raising and lowering my hand, as well as signing out and immediately signing back in.”

She said O’Neill was correct about the way tribal governments work. Just as county staff can’t make binding decisions without approval from the Board of Supervisors, tribal employees need their elected tribal councils to sign-off on any agreements. She also said that while the tribes did arrive at an agreement in principle on August 2, it was not considered a final, binding resolution.

“The rush to move this through the planning commission was a shock and surprise to the Tribe … ,” Vassel said. “It was quite shocking to be called a liar and the chair even alluded to another abhorred and racist saying but restrained himself from saying it out loud. These comments were based on false statements that the tribe signed a legal agreement. No one from the Wiyot Tribe ever signed a legal agreement regarding this permit.”

She said the Wiyot Tribe never intended to hold things up.

“We receive a $30 fee to process a permit and, done correctly, our comments are on the front end of the permitting process. The comments are built into the conditions of the permit. The development — if done in accordance with these conditions — moves forward timely.”

She said it’s not the tribe’s fault that the conditions of the original permit weren’t followed.

“This meeting felt like a show to discredit the Tribes and make us out to be the bad guys and make us appear to be at odds [with each other] when we were not at odds and have done nothing wrong,” Vassel said in her email. “The Wiyot Tribe staff did their jobs and followed the protocols and applicable laws. Our staff has worked diligently to conduct site visits, provide comments, prepare suggestions for conditions that might move this project forward at our own cost.”

The Blue Lake Rancheria also submitted a statement about the meeting in response to an Outpost inquiry.

“The core issue here is non-compliance with terms and conditions of building permits and other regulations,” the statement reads. It goes on to say that the tribe was “working in good faith” to resolve the matter but that the revised permit conditions were “inadequately detailed.”

No one from the tribe was available to attend the meeting in person, so the tribe was relying on the Planning Commission’s “careful consideration” of the letter it submitted beforehand, “which clearly reflected its recommended next steps, primarily more time to add necessary details to restoration plans among other proposed conditions,” the statement reads.

Like Vassel, the Blue Lake tribe said “inappropriate comments” during the meeting, particularly from Bongio, left the tribe “with a much lower confidence in the Planning Commission to adequately overcome its interests in this case and come to a fair and impartial resolution. “

We reached Bongio by phone this morning but he declined to say anything about the meeting on the record.

CLICK TO MANAGE