“All paths are the same. They lead nowhere.”

— Carlos Castaneda (as the fictional Don Juan Matus)

###

I enjoy reading broad-brush, overview books of science-y subjects I know little about. Somewhere in such books there’s usually a line that goes something like this: “To a Martian (linguist, biologist, physicist, philosopher) all (languages, species, colors, religions) are the same.”

The idea is that due to our necessarily anthropocentric, earthbound view of nature and culture, we miss similarities that would jump out at some intelligent being from someplace else. “The fish,” said anthropologist Ruth Benedict, “is the last to see the water.”

Thus an extraterrestrial being who reproduced via some other molecular coding than DNA/RNA, and who was composed largely, say, of silicon in a substrate of methane, rather than carbon in water, would be struck by the similarities of all life on earth and conclude that, roughly speaking, there was little structural difference between paramecia, grass, Republicans and us.

My contention here is that, to a first degree of approximation, a Martian neurologist would conclude that all thoughts are the same.

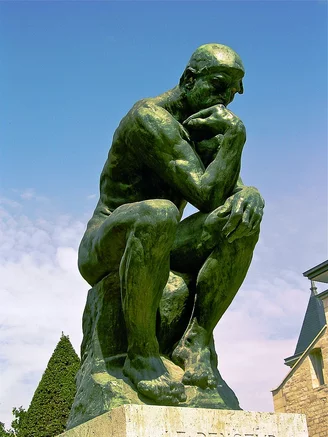

Photo: Andrew Horne, via Wikimedia. Public domain.

Sometimes

— meditating, kayaking, making love, walking a forest trail — it

seems that it’s all out there and nothing in here:

while there’s a whole lot of something being perceived, nothing is

actually doing the perceiving; whatever it is that is ‘me’ has

merged with everything else, so it’s all one. Paraphrasing Gertrude

Stein, “There’s no here here.”

Seems that way, but I’m pretty sure it’s all mindgames. Actually, of course it’s all mindgames. Whatever it is that is experiencing (and something is, by definition, else there would be no awareness) is no different from that which is experienced.

So titling a book (as Mark Epstein did), Thoughts Without a Thinker*, plays into the folk-wisdom idea of ‘nonduality,’ that it is possible to experience absent a thinker or a self (anatta). But what use is a thought if it isn’t perceived? What is an unperceived thought anyway? Is such a thing possible?

No. While it may indeed seem (to me!) that I’m having thoughts without ‘me’ being present, the question, “What, then, is perceiving this absence of a perceiver?” leads to absurdity. To perceive, or to know, or to be aware, is to come from the position of the perceiver, the knower, the one who is aware — however compelling the ‘no-self’ experience.

So I have these far-out experiences, and there’s this feeling that comes, expressed in words by something like, “Wow! How cool is that?!” with the inevitable undercurrent of, “How cool am I?”

* Despite his title (from pioneering British psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion), I suspect Epstein would agree with me. He stresses the importance of what he calls ‘bare attention,’ i.e. “…observing the mind, emotions and body the way they are.”

(Even writing this now: How cool am I to see through all the false teachings and promises? And cooler yet to acknowledge it…sigh.)

###

I have a huge admiration for Sue Blackmore, the British writer, teacher and interviewer on consciousness writ large. In her autobiographical In Search of the Light: The Adventures of a Parapsychologist, she tells of her transition from a ‘sheep’ (believing in all manner of parapsychological phenomena) to a ‘goat’ or a skeptic. She and I are on the same side, almost. Our paths diverge, however, over this crucial issue of ‘no-self’ or ‘non- duality.’ In the very last chapter of her very readable Consciousness: An Introduction, after 26 crisp and balanced chapters on the science of consciousness, she goes woo-woo on us. After decades of both studying consciousness from the outside and, as it were, experiencing it from the inside — that is, meditating — she wonders if the problem of consciousness might be solved by knowledgeable people who have ‘no-self’ experiences.

Blackmore writes, “Might the psychologists, philosophers and neuroscientists working on the problem of consciousness see non-duality directly for themselves? …This way the direct experience of nonduality might be integrated into a neuroscience that only knows, intellectually, that dualism must be false.”

###

My contention is that any apparent ‘direct experience of nonduality’ only seems that way, that it’s a mindgame. And that all the teachers and teachings and meditation and drugs and austerities and ‘spiritual’ practices bring us no ‘closer to ourselves.’ That is, this is as close as we ever get. This.

So that no thoughts are better and none are worse, none are more spiritual or less spiritual, none deeper or shallower. The thoughts of someone who is meditating for the first time — his or her very first minute on their cushion — are in essence no different from those of the Zen devotee who has spent tens of thousands of hours on their zafu.

Thoughts about thoughts are still thoughts. Awareness of an absence of thoughts, or an absence of self, is a thought. There’s nowhere to stand where we can say, “Now I’m perceiving from a unique, no-observer, non-dualist point of view.” All perception divides the world into the seer and the seen. Thought is dualistic by definition: it takes a thought to be aware of a thought. Thought cannot be aware of itself.

To a first degree of approximation, then: All thoughts are the same!

CLICK TO MANAGE