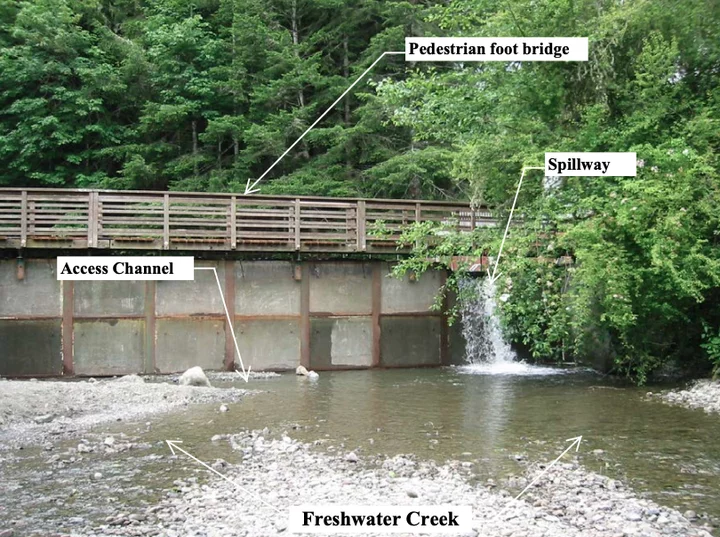

The Freshwater Park swimming hole. | Photos provided by the Humboldt County Public Works Department.

Freshwater Park will go without its iconic dam-made swimming hole for the third year in a row due to a torrent of logistical issues that will prevent the County of Humboldt from reinstalling the seasonal dam for another year, and possibly indefinitely.

Andrew Bundschuh, the Environmental Permitting and Compliance Manager for the county’s Public Works Department, told the Outpost that expired permits, the pandemic, drought, unfinished research for the dam’s fish ladder and modern environmental regulations have all contributed to the extended closure of the beloved Freshwater Creek pool.

“There’s still a lot of stuff to work out,” Bundschuh said.

For starters, the county’s decade-old permits for the dam and fish ladder expired in 2020. In order to reinstall the dam, the county needs to once again complete a successful review with various federal and state regulatory agencies, including the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the California Northcoast Regional Water Quality Control Board, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the National Marine Fisheries Service.

The seasonal dam.

“The permitting is basically for everything involved in installing the dam,” Bundschuh said. “There’s certain work that needs to be done. Boards are put in with a crane and we have to go in and smooth-out the creek bed to get the crane down there. During many winters, the fish ladder fills up with mud and silt. There’s lots of prep work covered in the permits. Then there’s the installation and the removal of the dam.”

A majority of these permits are designed to protect the fish that use the creek as a nursery and seasonal habitat. Cal Poly Humboldt Fisheries Professor Darren Ward said this includes three types of endangered salmon.

“Freshwater Creek supports three salmonids that are listed on the federal Endangered Species Act,” Ward said. “Coho salmon, chinook salmon, and steelhead trout, along with a suite of other native species including cutthroat trout, three-spined sticklebacks, sculpins, and lampreys.”

While local salmon populations have been smaller in recent years, Ward said that there is a lot of variation with annual breeding, and that there is currently an abundance of coho juveniles living in the Freshwater Creek.

“The spawning season this past winter was actually a really good one for coho salmon and there are lots of juvenile salmon rearing in the creek right now,” he said. “These juveniles need to spend a year growing in the stream before they head out to the ocean.”

In order to reobtain its Freshwater dam permits, the county will need to develop a thorough system for placing and removing the dam that won’t harm these endangered species. Part of that process, Bundschuh said, will include “electrofishing” — a method used by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to stun fish and other aquatic animals with electricity in order to sample or remove them from specific areas.

In the past, the county was able to install the dam by slowly scaring fish out of the area without electrocution. But Bundschuh said that the National Marine Fisheries Service now defines this method of frightening the fish as an example of illegally “taking“ endangered salmon.

“We hire consultants to do the electroshocking, which costs several thousand dollars,” he said. “The County Parks Department has been bleeding money for years. But the CDFW has agreed to assist us with the electroshocking and relocations, so we don’t have to spend $5,000 every summer. It’s a sign that the CDFW supports the project.”

By partnering with the CDFW, the county can piggyback on the agency’s scientific research permit exemption utilize trained CDFW employees to legally shock and remove listed fish species as long as the act is done for scientific research and collection purposes.

While the county may have found a manageable solution for its annual fish-relocation process, the most unpredictable problem still facing the Freshwater dam project continues to be the “megadrought” affecting much of the Western U.S.

Even with proper permits, Bundschuh said that the dam could not have been installed this year due to the creek’s extremely low water levels. The creek is a drainage basin for the Kneeland area that’s fueled by naturally flowing springs of rainwater and snowmelt that ultimately empties into Humboldt Bay. But with nearly all of Humboldt County in a state of severe drought, there simply isn’t enough water to fill the dam without dramatically affecting the endangered fish downstream. It’s a familiar problem for the county, which has been shutting down the swimming hole during years with insufficient water flow since 2001.

“With climate change, it seems like we’re getting more and more extreme drought,” Bundschuh said. “We’re really going to be dependent on creek flow conditions. In major drought years, we won’t be able to install the dam without detrimental impacts to fish downstream.”

The Marine Fisheries Service currently requires minimum flow conditions of more than 5 cubic feet per second for the dam to be placed in Freshwater Creek. When the county assessed the creek in May, a month before the traditional dam installation period, water flow had already dropped to 2 cubic feet per second — well below the required level for dam-supplied summer swims.

Freshwater Park County Supervisor Michael Orr, who’s worked on the Freshwater dam project for nearly 30 years, told the Outpost that these are the worst summer creek conditions he’s ever seen.

“In 30 years, I’ve never seen a flow as low as this,” Orr said. “It’s an extreme low. Thank goodness for those spring rains we had. The creek looks like it does in September during the driest of years.”

To make matters more difficult for the county, the permitting agencies are requesting that the dam never be installed before late June due to a small number of coho salmon that may still be out-migrating at that time. With strict flow requirements in place and rapidly dwindling summer water levels, Bundschuh said that the county is going to have a difficult time finding a slot where the dam can be installed.

“As a result, the dam may not go in every year based on flow conditions,” he said.”If we don’t meet those flow conditions in June, then the NMFS and all the national regulatory agencies can say: ‘You’re not installing the dam.’”

While dams are synonymous with environmental issues, Bundschuh said that Freshwater’s seasonal dam actually provides an ideal habitat for salmon during the hot summer months. This beneficial, man-made habitat, he said, is a major incentive for the permitting government agencies to work with the county and get the dam back in compliance.

The wooden fish ladder originally designed and developed by the Humboldt State Fisheries Department and used from 2001-2007. The current concrete fish ladder was installed in 2009 and still uses wooden baffles.

“When I started working for the County of Humboldt in 2006, right before we installed the fish ladder, we surveyed the pool behind the dam on Freshwater Creek,” Bundschuh said. “It provided some of the best habitat for fish within Freshwater Creek because it’s a deep, cold pool for them to hang out in. The agencies recognize that the dam creates a cool-water refugium. [Obtaining the permits] is just a matter of making sure we’re all on the same page.”

In addition to the beneficial pools, Bundschuh said that the dam also has a one-of-a-kind wooden fish ladder that was developed and installed with the help of Humboldt State University Students before the 2010 summer season.

The fish ladder’s wooden baffles.

“You’ll never find anything like this anywhere else,” Bundschuh said about the small community dam and its humble wooden fish ladder. “Basically, HSU Engineering and Fisheries students came up with the contraption. This thing was made out of plywood and was only meant to be used for a couple of years. Our permanent ladder is based on that design.”

This fish ladder has allowed the salmon, including juveniles, to navigate around the Freshwater Creek dam for more than a decade. However, the ladder’s wooden baffles, which were initially meant to be temporary, are now rotting away and the county is racing to develop new, more efficient baffles that currently don’t exist in order to meet modern-day standards.

Despite all these issues, Bundschuh, like a salmon swimming upstream, is actively working toward completing the permitting process, and hopes to reopen the swimming hole by next year.

“I hope to have it open by next year,” he said. “I don’t see any reason why it can’t, other than mother nature intervening. We have time. I feel confident that we will come up with something that works for the county and the agencies in order to establish a public swimming area for years to come.”

CLICK TO MANAGE