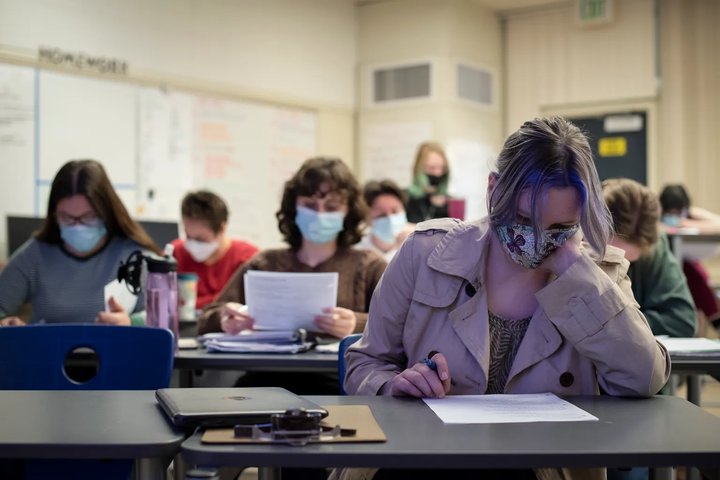

Some California school districts grew during the pandemic but didn’t receive additional money. Photo by Salgu Wissmath for CalMatters

While the vast majority of California’s school districts lost students during most of this past decade, hundreds of districts — mostly small and rural — have grown, emerging from the height of the pandemic with higher enrollment.

Most districts would welcome an enrollment increase and the per-student state funding boost that usually comes with it. But these growing districts were shortchanged when the state implemented blanket COVID-19 policies protecting districts that lost enrollment during the pandemic.

“The decision to hold districts harmless for declining enrollment came from a well-intended solution,” said Peter Birdsall, president of lobbying firm Education Advocates. “Even at the time, the concern was raised that some districts were growing. ‘Hold harmless’ actually hurt them.”

Because schools are funded on a per-student basis, when attendance drops, so does district revenue. For the 2020-21 school year, the state froze funding for school districts at pre-pandemic levels. So districts that saw enrollment and attendance plummet during the pandemic maintained their funding levels. But those that grew ended up with less money per student.

Education Advocates and the Small School Districts’ Association, an advocacy group representing these districts, estimate that 169 school districts, mostly small and rural, weren’t funded for all their students last school year.

“I think a lot of people look at the statistics and they say, ‘Where are the kids going?’” said Nicole Newman, superintendent at the Wheatland Union High School District, about 40 miles north of Sacramento. “But that’s not the case for every school district.”And while the shortchanged districts are asking the Legislature to make up the difference, key lawmakers appear to be split: Some say the state has an obligation to make these districts whole, but others say the districts should forget about the past and look forward to unprecedented funding headed for all California schools next year.

According to a CalMatters analysis, 189 of the state’s 940 school districts grew between the 2019-20 and the 2020-21 school years. The combined enrollment at those districts is about 10% of California’s total public school enrollment.

“This has never happened in California finance where a district isn’t paid for serving a student,” said Tim Taylor, executive director of the Small Schools Districts’ Association. “I know for a fact that if this had happened to any of the big districts, they would’ve been paid.”

By the end of the 2019-20 school year, Wheatland Union High had about 900 students. The following school year, it grew to 932 students, a 4% increase. Meanwhile, public school enrollment statewide decreased by 3% that first year of the pandemic.

The growth among many small districts reflected the availability of affordable housing, Newman and other district administrators across the state said. Residents from coastal urban areas started buying homes further inland when employers shifted to remote work during the pandemic.

In San Bernardino County, Lucerne Valley Unified School District didn’t budget for growth in the 2020-21 school year. Superintendent Peter Livingston said he submitted a budget to his county office of education that anticipated stable enrollment. He says if he had budgeted for growth, the county wouldn’t have believed him.

“The county would’ve kicked back our budget,” he said. “They would’ve said, ‘Where are these kids coming from?’”

But when the district’s enrollment, excluding charter schools, increased by about 40 students, the district budget was short $460,000, Livingston said. In a typical year, the state usually adjusts funding for growing districts, but because funding was frozen at pre-pandemic levels, Lucerne Valley Unified never got the money. The 840-student district had to hire four additional teachers and pay their salaries with reserve funds.

Newman is still hoping to get the $385,000 dollars her district should have received last year.

“I had to hire three more teachers, and those teachers had to get paid when I didn’t get the funding for those students,” Newman said. “In smaller school districts, that’s a significant amount.”

Newman said she had to dip into the district’s reserve fund to pay for extra staff. In total, Newman estimates that the 169 districts that grew in the last school year are owed $76.7 million — “a speck of water in the bucket for California,” she said.

“All we’re asking for is the funds that were not paid during that anomaly.”

— Shawn Tennenbaum, superintendent at San Benito High School District in Hollister

San Benito High School District in Hollister, about 30 miles east of Monterey Bay, gained 160 students between the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years. It grew by an additional 142 students this year. Since the start of the pandemic, enrollment has increased by nearly 10%.

Superintendent Shawn Tennenbaum estimates the district should have received about $1.2 million more in funding for the 2020-21 school year.

“We need every dollar we can get to support our students,” he said. “All we’re asking for is the funds that were not paid during that anomaly.”

Wheatland Union High has also continued to grow. This school year, the district’s enrollment increased by 14%, to 1,066. Lucerne Valley grew by a hundred students, or about 5%.

At issue is a one-year blip: The state reverted to normal and did pay growing districts the full amount this year, based on real per-student enrollment. Even as school funding will reach another historic high this year, these superintendents still say their schools are still owed for last year’s growth.

“My concern is that it sets a precedent,” Livingston said. “If we don’t fund growth, we’re not supporting students.”

State Assemblymember Kevin McCarty, a Sacramento Democrat who chairs the Assembly’s education finance subcommittee, said districts shouldn’t expect to be reimbursed for any growth in the last school year. Instead, he said, theys should focus on the “bigger picture” of unprecedented public school funding on its way next school year.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates a 3.5% increase, about $4 billion more, in guaranteed K-12 education funding next year thanks to recent increases in state revenues. McCarty said districts are worrying about small dollar amounts when there’s plenty of money heading their way.

“We have more funding for schools than we’ve had in the history of California,” McCarty said. “If you have to dip into your reserves for a year, that’s a small price to pay.”

Asm. Patrick O’Donnell has taken at least $1.7 million from the Labor sector since he was elected to the legislature. That represents 43% of his total campaign contributions.

But Assemblymember Patrick O’Donnell, a Long Beach Democrat who chairs the education committee, said districts that grew in enrollment last year “should be made whole” through the state budget. He said the decision to fund schools based on 2019-20 attendance was “made in haste” during the early months of the pandemic.

“We paid more attention to declining enrollment than we have to the few districts that have increased enrollment,” O’Donnell said. “Those districts that have increased enrollment deserve a seat at the table.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

CLICK TO MANAGE