On

page 36 of the 1895-1896 Humboldt County Business Directory is a

listing for “McGaraghan, P, speculator.” (i)

He is the only person in the entire directory with this occupation. (ii)

Speculators invest in commodities, such as stocks, that they believe will gain substantial value, at which time they can be sold for a handsome profit. McGaraghan speculated in land. George Washington, who is more famous for other endeavors, did likewise, purchasing 1,459 acres in rural Virginia in 1752. By 1800, when he executed his will, he owned 52,194 acres “to be sold or distributed.” (iii)

It is unclear how much land McGaraghan amassed in his role as a speculator, but by 1898 he had claimed one especially interesting parcel: a 160-acre piece of heavily forested hillslope, a half-mile square, that lay between the main Eel and South Fork Eel rivers about three-quarters of a mile south of Dyerville. (iv) The property, however, was not to remain in McGaraghan’s possession for long.

In 1898 much of the Bull Creek and Dyerville flats already belonged to Pacific Lumber, but there were several small holdings, like McGaraghan’s, and a large tract belonging to the Western Redwood Company that were not theirs. By 1911 many of these parcels, including McGaraghan’s, were in PL’s hands. The company owned much of the land on both sides of the main Eel from Scotia all the way upriver to Camp Grant. It owned part of the north slope of Grasshopper Peak. And it owned the Dyerville and Bull Creek Flats. (v)

Willis Lynn Jepson, probably the most famous botanist in the state, had “described the Bull Creek redwoods as the best of their kind.” (vi) Now PL could fondly contemplate the day when these “best” redwoods would be transported to their mill at Scotia and transformed into the best-quality lumber.

In 1911, though, the trees weren’t going anywhere because there was no effective way to move logs from Bull Creek to Scotia. It would take a major change in the county’s transportation infrastructure before anything could happen.

The necessary transition came in 1914 when the Northwestern Pacific Railroad (NWP) completed its line from Sausalito to Trinidad. Among the stations along the way was one called South Fork, which lay a few hundred feet east of the Dyerville Flat. It would be easy for PL to run a short spur line from the NWP tracks to the tract of towering redwoods.

But not yet.

Building the railroad near South Fork. Photo colorized by author.

Between Scotia and Dyerville, PL had been clearing redwoods for almost three decades, gradually cutting their way south as they followed the extension of the railroad. By 1916 they operated several logging camps in the Larabee Creek area, (vii) some four miles north of South Fork, while large tracts of uncut timber lay in three drainages between Larabee Creek and South Fork. Unless PL changed its logging strategy, it would be years before it got to Dyerville Flat.

But then another transportation transformation intervened. In 1917 three members of the patrician Bohemian Club decided to play hooky from the group’s summer high jinx on the Russian River and drive up the new Redwood Highway to see the forests of southern Humboldt County. (viii)

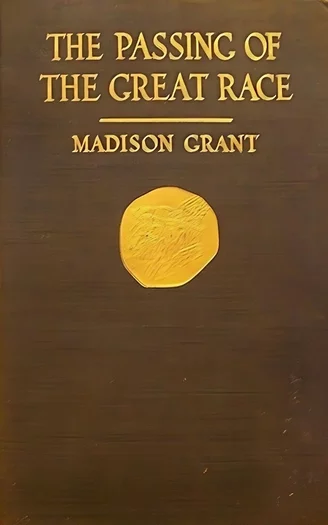

The three Bohemians carried with them some impressive credentials: Madison Grant was chairman of the New York Zoological Society, Henry Fairfield Osborn was president of the American Museum of Natural History, and John C. Merriam was a professor of paleontology at the University of California Berkeley. (ix) Less impressive, at least by later standards, were other portions of their resumés. All three were prominent supporters of the eugenics movement, which exalted the so-called “Nordic” race and promoted discrimination against other racial groups, including bans on interracial marriage, limits on immigration from non-European countries, and the involuntary sterilization of certain non-Nordic women. (x) In 1916 Grant wrote The Passing of the Great Race, a white supremacist screed that Adolph Hitler subsequently called “my Bible.” (xi) For Osborn, Merriam, and Grant, it was only a short step from this tainted theorizing to anointing the coast redwood as the sylvan representative of the “master race.”

The trio’s 1917 trip took them through the redwood forests along the South Fork and main Eel rivers, areas that until recently had been reachable only by wagon road. Merriam later described their descent from the roadway into the forest:

As we advanced, the arches of foliage narrowed above us and shade deepened into night… . Like pillars of a temple, the giant columns spaced themselves with mutual support, producing unity and not mere symmetry… .

But woven through this picture was an element which eludes the imagery of art. The sense of time made itself felt as it can but rarely be experienced. While ancient castles may tell us of other ages in contrasts of the seemingly fantastic architecture, living trees like these connect us by hand-touch with all the centuries they have known. The time they represent is not merely an unrelated, severed past; it is something upon which the present rests, and from which living currents seem to move.

We realized that the mysterious influence of this grove arose not alone from magnitude, or from the beauty of light filling deep spaces. It was as if in these trees the flow of years were held in eddies, and one saw together past and present. The element of time pervaded the forest with an influence more subtle than light, but that to the mind was not less real. (xii)

After subsequently arriving at the Arcata Hotel, Osborn and Grant sent off a letter to governor William D. Stephens informing him that “the superb woods of Bull Creek flats are incomparably grand” and indicating that creating “a Redwood Park of Humboldt County … would be one of the most gratefully received and long remembered acts of your administration.” (xiii)

The days passed, and Governor Stephens governed, but no park was forthcoming. In 1918 Grant returned to California and “endeavored to interest the California Highway Commission in securing a strip of timber along the new highways.” When no strip was secured, Grant and Merriam spent the winter of 1918-1919 “enlisting the support of a patriotic group of Californians” in creating a new conservation organization. (xiv)

The support was successfully enlisted, and in April 1919 the just-formed Save-the-Redwoods League (SRL) hired brothers Newton and Aubrey Drury “to handle advertising, publicity and a direct-mail membership drive.” (xv) Newton became the SRL’s first executive secretary (xvi) and soon had much more to “handle,” including an attempt to protect the Bull Creek and Dyerville flats.

In June Madison Grant again drove up the Redwood Highway. Along the South Fork he found a string of “small lumber camps” on 40-acre parcels, where the roadside trees were “doomed to the ignoble fate of being riven for railroad ties, for shakes or shingles, and perhaps worst of all, for grape stakes.” If this were not bad enough, Grant discovered that the California Highway Commission had indeed bought a hundred-foot-wide band of redwoods along the highway, but instead of protecting the trees had “actually contracted with the [previous] owners for the removal of the timber.” (xvii)

It hadn’t taken long. The railroad, less than five years old, and the highway, still under construction, had been yoked together in a system that all but guaranteed the destruction of southern Humboldt forest. “Tie hacks” could cut and split the roadside redwoods, take them by truck a few miles along the highway to the South Fork train station, and load them aboard the NWP’s railcars for transport to the lumber yards of San Francisco and the wineries of the Napa Valley. Grant, after his drive through the highwayside desolation, had sounded the alarm just as the brand-new SRL began to mobilize, but could a single organization move quickly enough to stem the tide?

The answer was no, a single organization couldn’t. But two could.

On August 2, 1919, the first meeting of the SRL’s board of directors was held in Parlor B of San Francisco’s Palace Hotel. (xviii) A week later, after a visit to Eureka by SRL leaders Grant and Steven Tyng Mather, the various local women’s clubs formed the Humboldt County Women’s Save-the-Redwoods League (HCWSRL). Within three months, it was 800 members strong. (xix)

At its start the SRL was led exclusively by men, most of whom were wealthy and held positions of power. They could reach out to others of their station not just in California but throughout the nation. They could speak the language of bankers and businessmen and could look a timber company owner in the eye as an equal. Their first president was Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane; their first secretary and treasurer was Robert Gordon Sproul, who later became the president of the University of California at Berkeley. (xx)

Contrastingly, the HCWSRL consisted chiefly of women, but “admitted men who were willing to work alongside [not above] them.” The organization was locally based and meagerly funded; its initial dues of 50 cents a year was soon reduced to 25 cents. (xxi)

On September 6, 1919, the HCWSRL made the news when the Humboldt Standard ran a photo of four well-dressed elderly women in front of a car displaying a banner with the slogan “SAVE THE REDWOODS.” As impressive as the sentiment were the pedigrees of the matrons expressing it: Lucretia Anna Huntington Monroe was a school teacher whose husband was a notable local attorney; Kate Harpst, who owned the car, was the widow of an Arcata lumberman; Mary Anne Atkinson was the wife of the owner of the Metropolitan Lumber Company; and Ella Georgeson’s husband was publisher of the Humboldt Standard, bank president, and former Eureka mayor. (xxii)

Four doughty dowagers enter the fray. Left to right: Lucretia Anna Huntington Monroe, Kate Harpst, Mary Anne Atkinson, Ella Georgeson. Driver Frank Silence sits quietly in the car. (HSU, colorized by the author.).

The same week as the HCWSRL car photo, a meeting of the preservation allies took place in Eureka. Madison Grant and other members of the SRL met with Laura Perrott Mahan, recently elected president of the HCWSRL, and other members of her group. Out of the meeting came a plan to prevent further roadside redwood cutting by paying the cutters $60,000 to put down their axes. (xxiii)

The groups had only two days to savor their accomplishment before PL began logging Dyerville Flat. PL president John Emmert claimed that winter weather made the steep slopes of the Larabee Creek drainage, where the company had been cutting, too slippery to continue, whereas the “nature of the topography” at Dyerville Flat permitted logging during the rainy season. This, Emmert claimed, would keep PL’s Scotia mill open and 800 to 1,000 employees at work. (xxiv)

Emmert was attempting to cast the situation as a simple adherence to the dictum of “business as usual,” but from the preservationists’ perspective, it was an immediate crisis. The Dyerville and Bull Creek flats were the jewels in a crown of riverside redwoods that would soon, hopefully, become a state or national park. Each stroke of the woodsman’s ax, each kerf cut by a PL worker’s saw was damaging one of the jewels and diminishing the chances that a crown worth saving would remain. The threat was felt so acutely that the “Humboldt County Chamber of Commerce … implored Emmert to stop the cutting,” and more than 50 of its members telegrammed him to that effect. Emmert’s response was to send five additional logging teams to Dyerville Flat. (xxv)

The Humboldt Times raged against Emmert’s latest act, claiming that soon the flat would be “ruined for National Park purposes.” (xxvi) Whether knowingly or not, the paper had revealed what was probably the true aim of PL. Where a Laura Mahan might see the trees as monuments to immortality and thrill to the vertical beauty of the tall trunks rising into the verdant overstory, a John Emmert might long to view them laid horizontally, sawed into sections, and sent off as the largest logs ever to be cut by PL’s mill. By beginning the cutting now, PL could inch its way across Dyerville Flat and on to the even larger grove at Bull Creek. Just a narrow corridor, with a rail line built along it, might be enough to ruin the flats for park status and thus ensure that PL’s lust for lumber would be fully satisfied.

With the SRL and the HCWSRL struggling to organize their campaigns, it was the Humboldt County Chamber of Commerce that rode to the redwoods’ rescue. They produced testimony by

. . . experienced loggers [who] were confident that even during the winter, other timber owned by Pacific Lumber could be cut without damaging the prospects for a national park. (xxvii)

With his credibility challenged, Emmert at first held fast to his plan, but he then agreed to reduce the Dyerville cutting. (xxviii) He indicated that the greatest part of the logging “was to come from the sidehills and not the flat,” that no logging would occur between the South Fork train station and the Redwood Highway at the Dyerville bridge, that PL would cut only enough timber for the winter, and that “a timber cruiser chosen by the Save the Redwoods committee … [would] lay out the timber to be cut.” (xxix)

In this way 1919 passed into 1920. Logging on Dyerville Flat stopped, at least temporarily, as the preservationists expanded their efforts to save endangered redwoods. In August 1921 the SRL dedicated the Bolling Memorial Grove at Elk Creek on the South Fork Eel (xxx) between Myers Flat and Miranda. It was the first in a long series of memorial groves, which were purchased with funds donated to honor particular individuals. (xxxi) It was also the first parcel of land in what was to become Humboldt State Redwoods Park, (xxxii) which opened in June 1922. (xxxiii)

Dedication of the Bolling Grove, 1922: Madison Grant, second from left; Henry Fairfield Osborn, fourth from left; John C. Merriam, to right of monument; Newton B. Drury, far right (SRL, colorized by the author).

At the time of its dedication, the Bolling Grove preserved 35 acres of redwoods. (xxxiv) It was a pretty, streamside location, but, in comparison to the entire South Fork redwood forest, it was tiny, protecting just a few dozen trees out of the thousands that lined the riverside highway.

And the rest of the forest would not be there forever. By 1921 some 21% of Humboldt County’s redwoods had already been cut. PL was logging its timberlands at an even faster rate: it had leveled 26,000 of its 69,000 acres of redwoods (xxxv) and was closing in on the South Fork.

But the tree-savers were making progress. By 1923 the SRL had acquired all but two parcels along the 14-mile stretch of highway between Miranda and Dyerville. (xxxvi) In 1924 the league announced an expansive four-project program that included saving redwoods at locations distant from the South Fork: at Prairie Creek, along the Del Norte coast, and at Mill Creek and the Smith River in Del Norte County. At the top of the list, however, was the grail of the preservationists — the Bull Creek and Dyerville flats. (xxxvii)

Four years had passed since PL had briefly logged on Dyerville Flat. Then on the evening of November 23, word reached Laura and James Mahan — the choppers were back! The next morning the Mahans drove south to see if the information was accurate. (xxxviii)

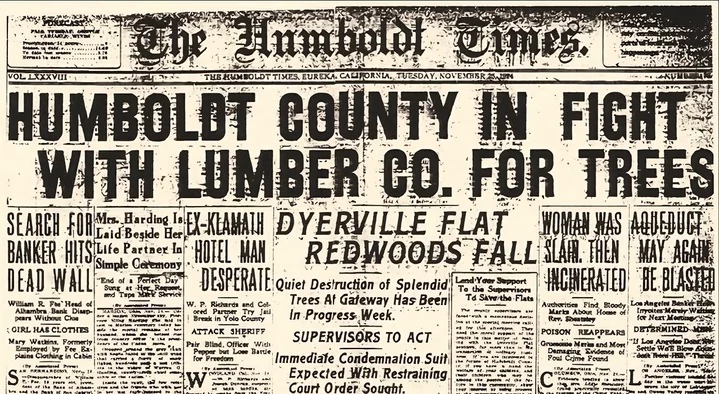

Laura Mahan reported the result to the Eureka papers, managing to meet the deadline of the Humboldt Standard, the city’s afternoon paper. The result was a small front-page article, “Dyerville Flat Redwoods Being Cut By Loggers,” (xxxix) which was being read hours after the Mahans made their discovery. The next morning, subscribers to the Humboldt Times were greeted with a double-banner headline that shouted, “HUMBOLDT COUNTY IN FIGHT WITH LUMBER CO. FOR TREES.” (xl)

Before their coffee grew cold, breakfast-time readers learned that not only were the “axes and saws of the Pacific Lumber Company” destroying the “hope of generations yet unborn,” but that within a few hours the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors were to meet in special session to decide what they would do about it. (xli)

Big news at breakfast. Colorized by the author.

When the board convened, its five members faced a room filled with concerned citizens. Laura Mahan was there with a delegation from the HCWSRL. Many allies from the Eureka Woman’s Club sat nearby, and there were contingents from the American Legion, the Rotary Club, the Elks Club, and the Humboldt State Teachers College. Residents from Ferndale, Loleta, Trinidad, Fortuna, Rohnerville, Garberville, and even tiny Carlotta were present. Newton Drury, secretary of the SRL, had come up from San Francisco along with Frederick Erskine Olmstead, who was preparing a plan for the league to buy 3,000 acres of the Dyerville and Bull Creek flats. (xlii)

The board viewed this staunch coalition of preservationists, considered the issue, and then voted unanimously to buy 160 acres of Dyerville Flat from PL and to seek an injunction to halt the logging. The board also instructed Humboldt County District Attorney Arthur W. Hill to begin condemnation proceedings against PL as the first step in acquiring the acreage. (xliii)

These actions inflamed Fred Murphy, a member of the family that owned PL. When, following the county supervisors’ action, the SRL asked PL for a meeting to attempt a non-confrontational solution to the conflict, Murphy not only opposed the SRL’s offer but also instructed PL’s attorneys to seek a temporary restraining order to prevent the condemnation of Dyerville Flat. The request was granted, but when it became apparent that the court would not make the restraining order permanent, PL dropped the case. (xliv)

Instead, PL switched to a new, more subtle tactic. It offered to allow perpetual public use of the southern portion of the Dyerville Flat in exchange for a pledge from the county to file no further condemnation suits. PL also indicated it would sell 300-foot-wide corridors on either side of the highway along the stretch that passed through the flat. (xlv)

The offer was designed to appeal not to the SRL and the HCWSRL but to a portion of their supporters. PL believed that the board of supervisors, local business interests, and a significant part of the general public would be satisfied with access to a small, cost-free portion of the Dyerville Flat rather than insisting on having the county purchase a larger, expensive parcel. If this wedge that PL was trying to drive into the preservationist movement was not powerful enough, the company attempted to strengthen it by including the following statement:

We appreciate the love of the beautiful which actuates those who would prevent any of the redwood trees of this state from being cut or destroyed. But we believe that such aestheticism should not be allowed to be carried to the extent where it destroys the property rights of others and prevents the carrying on of ordinary business operations according to the law of the land. (xlvi)

The appeal by a large business concern to the gospel of property rights had been used before and would be used many times later. But Laura Mahan and the HCWSRL were having none of it. They promptly made their opposition known and gathered the support of several sympathetic organizations. But other community groups, and most especially the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors, wavered. Newton B. Drury found that only one supervisor remained steadfast in his support of acquiring the flat. (xlvii)

On February 11, 1925, the situation reached a climax. That day the supervisors met to consider PL’s offer, which had gained enough traction within the community to put the preservationists on the defensive. If the SRL and the HCWSRL ever needed help, the time was now.

Unknown to almost everyone, they had it.

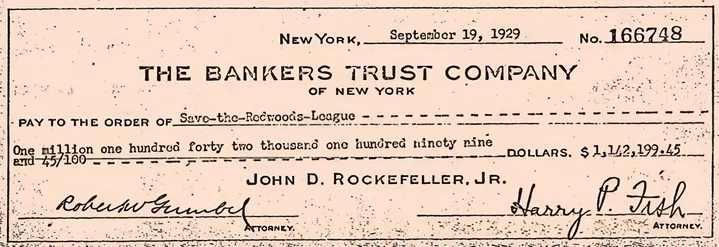

Back in 1923 the SRL was informed that John D. Rockefeller Jr. was interested in establishing a memorial redwood grove in honor of his mother. Quietly the league pursued the lead, learning that Rockefeller’s interest might exceed the purchase of a single parcel. Negotiations ensued, and in November 1924 Rockefeller sent the SRL a check for a sizable sum — $1,000,000. (xlviii) The next year, when Drury came up to Eureka for the February board of supervisors meeting, he knew he would be gambling on the future of the Dyerville Flat, but he now had a few extra chips to throw in the pot.

Colorized by the author.

Three weeks earlier, the SRL had received Olmstead’s study of possible redwood acquisitions. Olmstead indicated a preference for the purchase of three parcels: the Dyerville Flat, a series of small groves along the highway, and the entire 2,290-acre Bull Creek Flat. Based on this, the SRL prepared a resolution for the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors urging them to reject PL’s proposal and indicating that the league “had over three-quarters of a million dollars available for the purchase of [the flats at] Dyerville and Bull Creek.” (xlix)

February 11 arrived. At ten that morning, as the Humboldt Times reported,

Grandad and Grandchild, mother and father and young folk, thronged Judge Murray’s chambers at the courthouse … when the momentous question of the condemnation of Dyerville Flats by the Humboldt board of supervisors was to be discussed and decided upon in open meeting. Officials of the Pacific Lumber Company sat in a little group to the right of the courtroom, and on the left sat the members of the district attorney’s party, representing the board of supervisors and the people of Humboldt county. An air of expectancy hovered over all. (l)

Even the most extravagant expectations were fulfilled by what followed.

As the Times saw it, Senator H. C. Nelson, PL’s attorney, “presented his side of the contention in a logically clear and imposing manner.” In fact, the Times noted, “none other could have presented the case better, few so well.” However, Nelson “was pitting cold, unpalpitating [sic] legal lore against public sentiment, and that proved an insurmountable barrier.” (li)

No wonder then that District Attorney Hill gave what was considered “a wonderfully forceful presentation of the people’s side of the controversy.” Hill must have sensed that the audience saw him, a mere county official, riding knight-like to the rescue of the Humboldt populace, for he

. . . made it known in plain, unvarnished language, and in a ringing voice that carried conviction with it to every man and woman in the court room, that if The Pacific Lumber Company, or its legal representatives, insisted on throwing down to him, and the people of Humboldt County, and the nation the gauge of battle, that they would find him willing to take up the people’s standard and the people’s fight as far as it was necessary to take it to a successful conclusion. (lii)

By the Times’s standard this should have proved the death knell to PL’s cause, yet the debate continued. Nelson and Hill each fired another salvo. Irwin T. Quinn offered the Humboldt American Legion’s support for saving the redwoods. Donald MacDonald, PL’s treasurer, talked “about how large a payroll the company carried.” Later MacDonald “wagged and shook his finger” at James Mahan, who shook his finger back. (liii)

At a morning break Arcata businessman Henry Brizard had warned Drury that PL had succeeded in raising doubt among the supervisors as to the SRL’s ability to buy the Bull Creek and Dyerville redwoods and that Drury needed to “do something to offset the effect of that argument.” Drury had immediately phoned his brother Aubrey in San Francisco, asking for help in supplying proof of the SRL’s financial resources. Now the lunch break came and went with no word from Aubrey. (liv)

Back in the courtroom, the MacDonald-Mahan finger fight escalated. Mahan accused MacDonald of duplicity when the PL treasurer had earlier said that the company would sell the north Dyerville Flat if the necessary money was raised, but was now saying that PL wouldn’t do it. Drury, seated nearby, intensely wished that he’d heard back from his brother, but this thought was shelved as MacDonald and Mahan “approached each other, MacDonald stiffening and straightening and Mahan shaking his fist.” Quickly Drury “interposed … that all should be amiable and no personalities indulged in.” (lv)

What MacDonald and Mahan intended to do next will never be known for, as the Humboldt Times reported,

At this dramatic moment three telegrams in rapid succession were handed to Drury, who read:

“$700,000 in funds on hand to save redwoods.”

“$750,000 in funds on hand to save redwoods.”

“$750,000 in funds on hand to save redwoods.” (lvi)

The messages came from William H. Crocker, president of the Crocker National Bank; J. D. Grant, SRL vice-president and a director of a half-dozen banks; and James C. Sperry, “a prominent figure in California financial circles.” (lvii) The audience was thunderstruck. Drury later said “you could have heard a pin drop.” (lviii)

Aubrey Drury had come through, perhaps more so than he realized. It appears that Newton Drury wanted three telegrams, all confirming that the SRL had a total of $750,000 available to buy redwood timberlands. But one of the three responders telegraphed the figure of $700,000 instead. When Drury read the telegrams to the audience, this discrepancy in the amount of available funds apparently created the impression that each telegram was about a separate pledge of money. This led to the conclusion that the SRL had not a mere $750,000 on hand but a whopping $2,200,000 instead.

Fortified by the dramatic, if somewhat misleading, impact of the telegrams, the board of supervisors voted unanimously (lix) to accept the SRL’s proposal, “calling for amicable negotiations if at all possible, condemnation proceedings if necessary, and league acquisition of Bull Creek and Dyerville Flat [sic].” (lx)

The miracle of the three telegrams was not the only pivotal event of the day. A typical Humboldt County winter rainstorm provided a second situation that greatly benefitted the SRL. After the supervisors’ meeting concluded, Newton Drury and Albert W. Atwood, who was writing about the redwoods for The Saturday Evening Post, boarded the evening train for San Francisco. The torrential rain, however, had blocked the tracks and so the men deboarded in Scotia, where they planned to stay overnight in PL’s Mowatoc (later renamed Scotia) Inn. PL president John Emmert learned of their arrival, and, in an act of unexpected but fortuitous hospitality, invited Drury and Atwood to dinner. The meal, according to Drury, was “wonderful,” and Emmert was “particularly friendly.” The result was that the SRL and PL were able to defuse their confrontational relationship and embark on more amicable negotiations for the league’s acquisition of the Bull Creek and Dyerville flats. (lxi)

The Mowatoc Inn, site of Drury’s delightful dinner (colorized by the author).

That evening at Scotia, neither Drury nor Emmert had any idea how long those negotiations would last. As it turned out, they were prolonged beyond the most pessimistic projections. Six months after dining with Drury, Emmert met with John C. Merriam, the SRL president and proposed that the league consider acquiring some 10,000 to 12,000 acres in Bull Creek rather than the 2,000-plus that was the SRL’s current objective. Merriam left the meeting convinced that PL “would not willingly sell a smaller area.” (lxii)

The league was trapped. Here was an offer of a tract of redwoods whose size vastly exceeded their expectations, but the cost of which would be far beyond the funds they could reasonably expect to generate. Agreeing to the proposal might strain the SRL beyond the financial breaking point, but the only other option, instituting condemnation proceedings for the smaller block of land, was something the SRL was unwilling to attempt. The league decided to accept PL’s offer. (lxiii)

PL and the SRL agreed to have a three-person arbitration board determine the value of the forestland, which would then form the basis for negotiations about the final price. In 1927 the arbitrators returned a figure of $5,600,000, far higher than the league had hoped. With certain ancillary costs added, the final cost would be $6,000,000. (lxiv)

Raising the money was a daunting task, but events soon transpired to make it easier. In November 1928 California voters approved a $6,000,000 state park bond that would match public contributions, dollar for dollar, up to that limit, so that the combination of donations and bond money would equal $12,000,000. The bond measure passed statewide by nearly a three-to-one margin. Laura Mahan noted that in Humboldt County the margin was five to one. (lxv) Two months later Rockefeller, having visited the Bull Creek and Dyerville flats in 1926, (lxvi) indicated that he would donate another million dollars to the cause if the SRL could match it by the end of 1930. This meant that any donation to the league would, up to a point, effectively be quadrupled — doubled by Rockefeller’s pledge and that amount then doubled by the state bond money. The SRL’s fundraising goal finally appeared reachable. (lxvii)

Now the main hurdle was having PL agree on a price. From 1928 to 1930, while the flats at Bull Creek and Dyerville remained uncut but vulnerable, the issue remained unresolved. As the impasse became apparent, the recently formed State Park Commission became involved in the negotiations. Then, in 1930, A. Stanwood Murphy, soon to become president of PL, joined Emmert at the meetings. At first his presence had no effect, and the SRL edged toward the solution it had long dreaded, condemnation proceedings. (lxviii) But Arthur E. Connick, Eureka bank president and future SRL president, began talking with Murphy. Connick knew the temper of Humboldt County preservationists and their allies, and he warned Murphy that a refusal by PL to settle would probably result in a boycott of redwood lumber, abetted by articles in the Saturday Evening Post and other magazines condemning the “wanton devastation and destruction” of the redwood forests. (lxix)

Murphy blinked. In April 1931 Connick and Murphy announced a compromise. The purchase area was reduced by nearly a third, from 13,239 to 9,000 acres, and the price would be substantially less than what PL wanted: $3,212,220. A survey of the forest showed what the preservationists were getting for their money: “105,392 redwoods of a diameter of more than 20 inches” plus 34,836 smaller redwoods and 21,313 Douglas-fir trees. (lxx) If the purchase price was applied solely to the larger redwoods, the cost came to $30.48 per tree, by anyone’s standards a stupendous bargain.

Dedication of the Bull Creek-Dyerville forest, September 13, 1931 (colorized by the author).

By June PL had signed off on the sale, followed by the approval of the State Parks Commission. The transaction, six years in the making, was completed in August, and on September 13, 1931, over a thousand celebrants gathered beside the Bull Creek road for the dedication of the Bull Creek-Dyerville forest. (lxxi) It had taken the efforts of two Save-the-Redwoods leagues, two $1,000,000 donations — and three timely telegrams — but the greatest redwood forest on earth had finally been protected.

###

Jerry Rohde is the author of many books on Humboldt County History, including 2022’s Southwest Humboldt Hinterlands, from which the preceding is excerpted, with the author’s permission. All of Rohde’s most recent work, which explores Humboldt County history on the regional level, is published by The Press at Cal Poly Humboldt and is available for free download under a Creative Commons license, as well as for sale in traditional formats. You can browse all the Press at Cal Poly Humboldt’s titles at this link.

Want more local history in your life? Consider joining the Humboldt County Historical Society, a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of the society’s journal, The Humboldt Historian, at this link.

###

FOOTNOTES:

i Spencer 1895:36.

ii The 1893-1894 directory listed three other speculators. By 1895 one of them had become a woodsman, one a “general trader,” and one was no longer listed (Standard Publishing Company 1893:25, 49, 54, 75.)

iii Library of Congress 2019a.

iv Lentell 1898.

v Denny 1911.

vi Engbeck 2018:242-243.

vii Belcher 1921:2.

viii Engbeck 2018:198.

ix Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:27.

x Platt 2019a.

xi Kuhl 2000:85. In June 2021 the California Department of Parks and Recreation removed a monument dedicated to Grant from Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park (Cahill 2021a). At the Founders Grove on the Dyerville Flat in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, two signs were replaced with a single sign that acknowledges the racism of two of the “founders,” Grant and Henry Fairfield Osborn (Carter 2022).

xii Merriam 1938:1898-99.

xiii Engbeck 2018:201-202.

xiv Grant 1919:116.

xv Engbeck 2018:212.

xvi Savetheredwoods.org 2020.

xvii Grant 1919:99, 103.

xviii Engbeck 2018:214.

xix Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:36-38.

xx Grant 1919:115.

xxi Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:37.

xxii Irvine 1915:285; Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar [!] 1936a:7; Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:37-38.

xxiii Engbeck 2018:218-219.

xxiv Ferndale Enterprise 1940a; Engbeck 2018:219.

xxv Engbeck 2018:220.

xxvi Engbeck 2018:220.

xxvii Engbeck 2018:220.

xxviii Engbeck 2018:220.

xxix Ferndale Enterprise 1940a.

xxx Engbeck 2018:233.

xxxi Engbeck 2018:233, 235.

xxxii The name was later changed to Humboldt Redwoods State Park (Rohde and Rohde 1992:36).

xxxiii Humboldt Beacon 1922a:4.

xxxiv Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:52.

xxxv Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:49, 53. The rate here was almost 38%.

xxxvi Engbeck 2018:238.

xxxvii Engbeck 2018:240-241.

xxxviii Humboldt Times 1924a:1.

xxxix Humboldt Standard 1924c.

xl Humboldt Times 1924a:1.

xli Humboldt Times 1924a:1.

xlii Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:97.

xliii Engbeck 2018:250; Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:97.

xliv Engbeck 2018:251.

xlv Engbeck 2018:251.

xlvi Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:100.

xlvii Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:101-102.

xlviii Engbeck 2018:248-249; Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:104.

xlix Engbeck 2018:252.

l Humboldt Times 1925a:2.

li Humboldt Times 1925b:1-2.

lii Humboldt Times 1925b:2.

liii Humboldt Times 1925b:2.

liv Engbeck 2018:254.

lv Humboldt Times 1925b:2.

lvi Humboldt Times 1925b:2. Drury, in an interview 47 years after the fact, gave a much less dramatic account, claiming that the telegrams arrived at intervals of several minutes and that he only read them aloud “when there was a pause.” (Engbeck 2018:254). It is thus uncertain as to what actually happened, but I have chosen to use the Humboldt Times version, which was written at the time of the event and of course is much more exciting. Readers of this endnote can choose which version to believe.

lvii Engbeck 2018:255.

lviii Engbeck 2018:255.

lix Humboldt Times 1925b:2.

lx Engbeck 2018:255.

lxi Engbeck 2018:255.

lxii Engbeck 2018:256.

lxiii Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:117-118.

lxiv Engbeck 2018:272; Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:117-118.

lxv Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:119-120.

lxvi Humboldt Times 1926a.

lxvii Engbeck 2018:274.

lxviii Engbeck 2018:274-275; Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:140.

lxix Humboldt Standard 1931d; Engbeck 2018:274-275; Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:140.

lxx Humboldt Standard n.d.a.

lxxi Humboldt Standard 1939c; Engbeck 2018:274-275; Wasserman and Wasserman 2019:140-143.

CLICK TO MANAGE